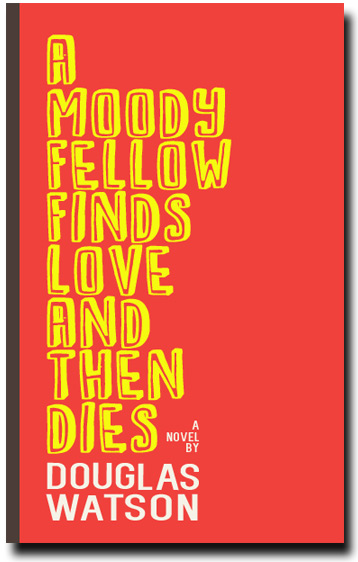

Outpost 19, 2014

With a tongue-in-cheek title like A Moody Fellow Finds Love And Then Dies, you might think Douglas Watson’s first novel is just another sad and funny tale tall on charm, but short on consequences. Published by Outpost19, an indie house that promises “provocative reading,” A Moody Fellow Finds Love And Then Dies is more than just a funny fable. Just 170 pages, the novel is filled with thought-provoking insights about the differences between male and female perceptions of love, the absurdities of the art world, and, of course, the troubled hearts of moody fellows.

Narrated by a sadistic and omniscient first-person plurality of narrators (“we, the narrators”), the novel’s comic self-awareness is highly entertaining and showcases Watson’s line-to-line eccentricity.

Halfway back to his dorm, Moody came very close to being murdered by a bolt of lightning. Indeed, we were in the mood to see him killed, but it occurred to us that he hadn’t found love yet, which meant that according to the terms laid out at the beginning of the narrative, he had to be allowed to live a bit longer—and so we nudged the lightning bolt twenty feet to Moody’s left, where it slammed into, or rather through, a chipmunk, poor thing. Who now would provide for that chipmunk’s family?

Moody Fellow’s search for love starts with his first kiss in exchange for his math homework and ends after his final breath. Before ultimately finding love, he gets heartbroken at every turn in bald, brutal, even pornographic ways—character developments that one might expect from a sadistic, omniscient narrator tittering backstage. First, there’s Amanda, the conniving and beautiful performance artist that Moody catches having sex with another man in the dorm common-room. Then there’s Jane, the cute, freckled girl with a taste for the football player Moody is not. Then there’s Daphne, the earnest war protester who earnestly prefers men named Pablo. Then there’s Clara, the pious social anthropologist who cries during sex, except with the same man named Pablo. And that’s just the first third of the book. When the sculptor Chad and his ironically named shrink Dr. Love are introduced—both similarly moody fellows with love troubles—you start to notice a fable-like uniformity to Watson’s sad sacks and their fundamental misperception that love is something in which you fall rather than something in which you participate.

Basically – though he wouldn’t have put it this way – Moody resented having to go out and become part of the world. He preferred to be a world unto himself. He wanted to fall in love, of course, but otherwise he was happy to think his thoughts and feel his feelings and be impressed by his impressions.

Moody, Chad, and Dr. Love’s passivity invites a Game of Thrones -level of female cruelty. As if the bawdy dorm common-room incident wasn’t torture enough, Moody is later forced to watch in horror as the aforementioned exhibitionist Amanda has public sex with her boyfriend in a performance art show ironically named Faces. I couldn’t help but wonder whether Watson was trying to say something wicked about the nature of women or wicked about the nature of men or both.

Take Kate, for instance, one of Moody’s many prospects. She wears,

…exuberantly multi-colored leggings, a short black skirt, a white button-down shirt, and, over the shirt, a red-and-green cardigan that ought to have clashed horribly with the leggings but somehow managed not to…Her hair was dyed ruby red, and topping things off was a small black hat that, Moody intuited, would be more accurately referred to as a chapeau.

She’s “full of rage” at the sudden and unexpected death of all her family members in separate, very unfortunate incidents. Kate is an angry, indie girl fantasy straight out of a Saturday morning cartoon version of Reality Bites. Do such women actually exist? Is it Kate who must soften her edges or Moody who needs to stop conjuring women as nerd-boy fantasies?

Like Moody, Dr. Love is also a sophisticate, a man who can be exhilarated by his client Chad’s sculptural tribute to a dead friend, killed by a “falling train” (was the friend standing beneath a bridge?). And yet, his thoughts also drift to female infidelity and a sexually frustrated monumentalization of an undefined female beauty.

Dr. Love drifted off into a morbid fantasy about walking in on his wife and her chief financial officer as they were engaged in the most ancient of personal misdeeds, then dragging them both by the hair to the nearest set of railroad tracks and tying them down together to await the weight of the judgment against them. He recognized that the fantasy was unhealthy.

Brushing his elbow now and sending him into a different kind of reverie was the elbow of the beautiful sex/art girl. It had been an accident, he saw, the contact. Still, he would treasure the memory of it until the day he died, if not longer.

Outpost19 fulfills its provocative promise as I, the reader, found myself debating the thematic goal of these uneasy gender depictions. Why are the women described as “dark,” “lethal,” “radicalized,” and “angry,” while the men are monolithically feckless, sad, sensitive, and can’t even cook a pot of spaghetti? The women become active in anti-war protests and new art movements, while the men remain sullen, playing classical piano and taking Cubism literally. Do our moody fellows really deserve to find love if the women are so much more engaged in the world?

If you chalk up the uneasy gender depictions—perhaps played for laughs—to Watson’s eccentricity, you will be charmed by this unusual, very funny book starring this elf-loving classical pianist. The central thesis of Watson’s fable still holds true: everyone—male or female—deserves to find love, even as the harsh, uncaring world exists to wrest it from our grasps.

+++

+