Beating Windward Press, 2012

There’s a certain kind of kid that starts off his teen years with a deck of tarot cards, and adds to it a copy of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the Necronomicon (for sale at the Walden Books at the Auburn Mall), and the writings of Alistair Crowley. I was the kind of kid who was looking to magic and the supernatural more gently, for some kind of sanction, either of the way things were or that they really were unjust. Magic promised a higher order, a sense of rightness that was more emotionally recognizable than literally apparent, and that made it deeply appealing. It had the promise of good fiction, and the stamp of an order that seemed unquestionably true.

The stories collected in Karen Best’s A Floating World are suffused with that same magic: her characters exist alongside elemental figures who see to it that everyone gets what he or she deserves. Cheaters and spurned lovers reappear often in this collection, creating a cast of romantic victims and criminals that starts in the first story, “Eternity in Ice” when protagonist Gwen loses her man to a Nordic ice princess named Thora and then winds through most of the stories, like “Thread” and “Air and Water” and all the way through to the adulterous and doomed protagonist of the collection’s final story, “Violets, Covered in Snow.”

The way magic can mete out justice or at least even up the scales has a strong appeal for a certain kind of reader and protagonist, ones who may spend more time on the fringes of the larger social groups. The protagonists in Best’s stories often seem similarly isolated from the social weal: there are lots of young women, for example, who feel like the world is passing them by. There’s the nameless protagonist of the title story, “The Floating World” whose “legs—fully formed above the knee—tapered below it to stumps that would never bear her weight” (53), or else the polymorphously perverse protagonist of “Air and Water,” looking for some “figure to come to her and reach out its slender arms, until their surfaces will also mingle, atoms mixing in the no-space between them” (38). In Best’s stories, the fantastic provides a kind of magic mirror, telling the characters (and we readers) what they really deserve. So when the protagonist in “Beauty Asleep,” a graphic artist for an ad agency unconsciously draws a rape scene as part of a campaign for a sleep aid, he deserves to be seen as a rapist. If your boyfriend is stolen away by a sexy ice princess named Thora, you probably were too dull, too sheltered and provincial, to deserve him anyway. Magic is a shortcut to what great stories always do, forcing characters to confront who they always were but failed to see.

The best stories here, though, allow their magic to unsettle our sense of right and wrong: in “Our Lady of Wormwood,” twenty-something supermodel Maryska visits Chernobyl and meets there an embodied void who steals her face and makes her reflection a mirror of its own emptiness. Since Maryska is a model, losing her face has a sort of poetic balance—but it’s never clear what she did to deserve it, or the horrible beating she takes at the hands of Chernobyl’s military guard. This surplus of nastiness is thrillingly bleak: magic is another errant force loose in the world, another cause for worry, like rape, or addiction, or cancer, something that happens to the deserving and the undeserving alike.

Similarly, in “Lovecraft,” the blasé and thrillseeking narrator goes on a date with a high school lover only to hear him relate a surreal past experience (the sky rained hail-sized bits of glass), exactly the kind of magic she looks for in her present but which he assures her she was present for in the past. But she can’t remember it; this lacuna in her past lurks, to gnaw at the character’s sense of self. The writer Lovecraft’s elder gods didn’t keep a book like Santa of who’d been naughty and who nice, and the fantastic elements in these two stories and a few others, like “Violets, Covered in Snow,” don’t either. Sometimes something happens and your life changes in ways you’re hopelessly unprepared for. This, to me at least, seems like a mature take on horror, on magic, on chance, and the way it, too, can shape a life. The stories where this ethos ruled were ultimately more meaningful, challenging and even shocking compared to the neater reversals of stories like “When She Wakes Up,” “Beauty Asleep” or “The Worm Vine,” with their pedestrian score-settling. A story like the title story, “The Floating World,” which avoids most of the magical elements of the other stories (aside from some magically effective surgery) still comes across as a little too neat, with its return to the water for its sea-haunted narrator.

Interestingly, Best’s writing is uninflected whether relating the magic or mundane; describing the way a lover shifts in bed, she writes, “She turned slightly away and groaned” (91), and of the evidence of saintly miracles she notes, “The statues have little white dishes beneath them to catch the tears and holy oil that issue from their plaster eyes” (79); Best’s writing style is less incantation than inventory, a vehicle to carry the tales more than an engine of surprise, discovery, or beauty.

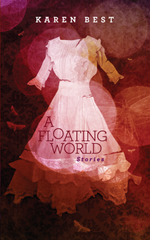

The last piece in this collection, “Once Upon a Time: The Uses of the Fairy Tale,” is an essay on, as the title suggests, the way three contemporary writers integrate fairy tales into their work. It’s revealing, though, that two of the three writers Best analyzes, Munro and Trevor, are traditional realists who, when they do use the tropes of fairy tales, they do this to bring the quotidian reality of their characters lives into sharper focus. The everyday isn’t as strong a factor in Best’s stories, though they aren’t, in general, as outside the realm of the real as Angela Carter’s work, for example, another obvious influence. I wonder if Best chose the writers she did to satisfy her committee, rather than turning to writers like Shirley Jackson or maybe Kelly Link whose aims seem more aligned with Best’s. Best’s work is more informed by genre writers, and the blood and emotion those writers bring to the page, than she is by these realists, at least in the stories presented here. This seeming disconnect only emphasizes the oddity of including an essay which seems to misrepresent what really concerns the stories that precede it. Beating Windward Press, which lay out a very appealing cover and design for the book, promise story and character. Best’s characters are recognizable but sometimes familiar enough to be types, and some of her narratives feel the same, rehearsing familiar scenes, conflicts, and resolutions. The writer and the press seem well-matched: both mix traditional, even commonplace virtues, with hints of something more exotic right around the corner.

+++

Karen Best is a bitter Goth masquerading as a nerdy bookworm. She holds an MFA from the University of Central Florida and her writing has appeared in Our Stories, ETC, and Filament Magazine. Early exposure to the paranormal, mythology, fairy tales and Edgar Allen Poe has left her with an abiding interest in dark stories and dressing entirely in black. Karen blogs on Gothic aesthetics at www.LashesAndStars.WordPress.com. She lives in Florida with her obliging husband and several cats and can be found online at www.KarenDBest.com.

+

Matt Dube teaches creative writing at a small University in the rural middle of the United States. His stories have appeared in Sleet, 42Opus, Conte Online, and elsewhere. He is the fiction editor for the online journal H_NGM_N.