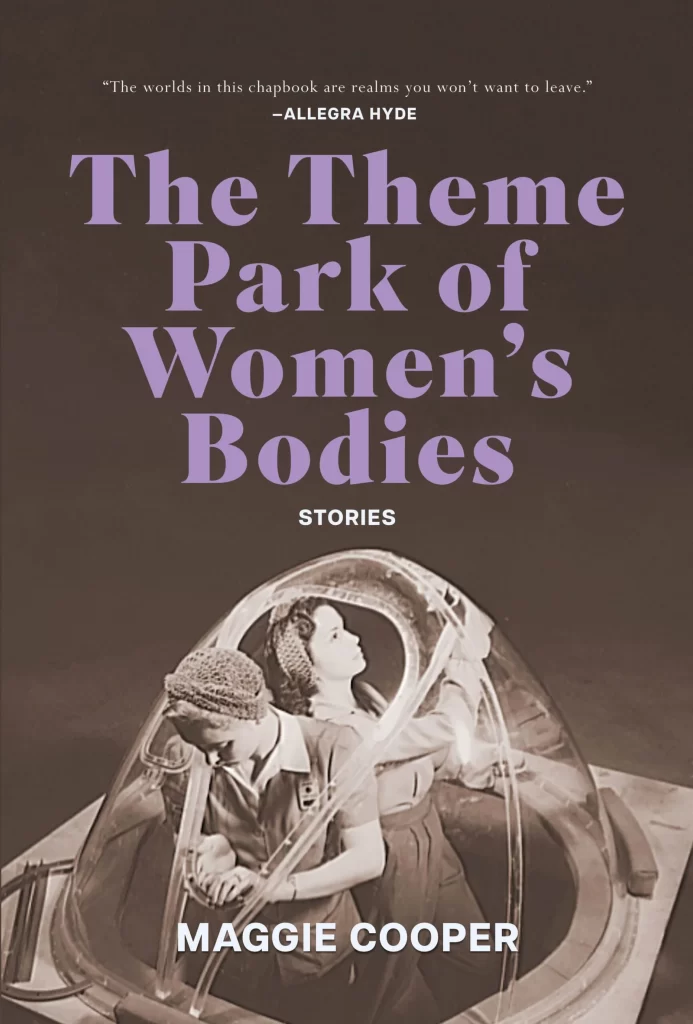

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Maggie Cooper writes about The Theme Park of Women’s Bodies from Bull City Press.

+

I am an inveterate googler. I try to control myself: I don’t google during theatrical performances, at romantic dinners, when I’m in the middle of a run or teaching a class. But in my writing life, dear google is my near-constant companion.

I wish I had kept a list of everything that I had googled while writing the nine stories in The Theme Park of Women’s Bodies, but that would have required a level of premeditation I lack. Still, it isn’t hard to recreate a partial list of search terms that went into the creation of the chapbook.

Consider:

Theme park list of rules

GORP recipes

How many caves

Stalactite vs. stalagmite

Cookout menu

Christine de Pizan

Chinese gooseberry

List of fruits

synonyms for jam

Parts of a ship

Units of energy

My imaginary writer self does much more interesting kinds of research. Imaginary me is visiting the archives of architecturally impressive museums and finding delicious morsels in the footnotes of handwritten manuscripts. She’s befriending knowledgeable elder academics in order to delve in their obscure areas of expertise. She’s wearing a fancy hat and sneaking into exclusive luncheons at the Kentucky Derby (with much admiration for writer Wendy Francis, who has actually done this!) or enterprisingly talking her way backstage at the opera. She’s going on ridealongs with ambulance drivers or doing interviews at a queer commune or attending the birth of a litter of kittens.

Meanwhile, real-life me is crouched over my computer like a gremlin, cherry-picking from the first page of google results, and whimsically selecting a favorite from a “list of German names” or scrolling the Wikipedia article about the colonial history of the kiwi fruit. When compared to the exploits of my imagined writerly self, it begins to feel as though googling is the worst kind of research—lazy, unimaginative, and completely lacking in vibes. In my defense: googling stuff is also easy, efficient, and doesn’t require days off from work or expensive plane tickets.

Of course, plenty went into this chapbook other than the results of my search engine perusals. These fifty pages—which together make up a collection of fabulist stories about women-centered spaces, desire, bodies, and the promises and limits of feminist solidarity—couldn’t have been written if I had not lived for several decades in a woman’s body in a patriarchal society. If I had not spent my childhood reading fantasy and science fiction and historical novels about improper ladies. If I had not done the all-important preparation of drinking Cookout milkshakes in North Carolina and eating jam made by Trappist monks in Central Massachusetts.

But I would be lying were I not to also acknowledge the role of the internet in my humble literary toilings. This leads me to what I’ll only somewhat ironically call my Descartian theory of the search engine: I think, therefore I google. Or perhaps: I google, therefore I am. Or, finally: we are what we google? In my writing, it feels like some combination of all three of these is accurate.

The good: googling allows me to bring specificity and texture to my prose, helping me to zero in on the fast food order of my main character or lend physical heft to my description of the ship helmed by my intrepid lady pirates. Googling reminds me of the word I’ve forgotten or teaches me a new one, delivers the facts to sit alongside my fancies. I can google on the fly, thereby diminishing the possibility that, after I arise from my writing space, I get distracted by the dirty dishes in the sink and never return to drafting. And perhaps most of all: google is vast, reminding me of the wondrous immensity of the world that my fiction hopes to capture.

Sure, googling can be its own distraction, but isn’t that true for every type of research? Sure, googling is lazy, but can’t we occasionally embrace the opportunity to be lazy in a world obsessed with discipline as virtue and suffering as art?

At the same time, I’m becoming increasingly preoccupied with the darker side of these searches. There is an environmental effect of every search; the proliferation of AI-aided processes and their even greater climate consequences has reminded many of us that what seems free to us is not, in fact, without costs for the planet. Then there is the reality that, while I use “google” as a generic term, in actual fact, most of the time I am capital-G Googling, enriching a particular corporation and allowing my findings to be informed, shaped, and no doubt twisted by one algorithm and the forces that make it what it is.

Curiosity is one of my core values as a writer, and looking things up on the internet can be a way of satisfying and cultivating that curiosity. But there are other ways of honoring my curiosity, too: going outside and looking at something other than a screen, having conversations with real live people, reading books. I’m not about to give up the search engine as a research tool, but when I am trying to be more thoughtful about what goes in my search bar—when I’m searching as a reflex, and when I really and truly want to know.

For 100 days last spring, I painstakingly recorded my complete google search history, which revealed how much time I spent perusing the menus of restaurants in cities where I don’t live and typing in people’s names followed by the phrase “writer.” Other searches from this period included: “apple oat julia turshen muffins” (they are great, in case you’re in search of a muffin recipe), “egypt camels,” “books about loneliness,” “nugochi lamp,” and “funny amusement park meme.” The full spreadsheet runs more than 3500 entries and reads, mostly, as a recap of my obsessions and interests at the moment. It’s a ridiculous document, an indulgence of whimsy and technophilia and the proverbial rabbit hole. It’s a troubling testament to the way that so much of what we know is shaped by capitalism and mediated by technology. But it’s also, on some level, a testament to my ability to wonder, a record of little prayers cast out into the internet by someone wanting to learn, quite sincerely, something she does not. What else but wonder and little prayers is fiction made of?

+

It seems only appropriate to include a list of the things that I googled while writing this essay:

trappist monk jam

google inventor

wendy boston writer

wendy francis writer

“rabbit hole” history

quotes with “wonder”

“wisdom begins in wonder”

+++

Maggie Cooper is a graduate of Yale College, the Clarion Writers’ Workshop, and the MFA program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She is the author of the prose chapbook The Theme Park of Women’s Bodies (Bull City Press, 2024), and her writing has appeared in The Rumpus, Ninth Letter, Inch, and elsewhere. Maggie lives with her spouse in the Boston area and also works as a literary agent.