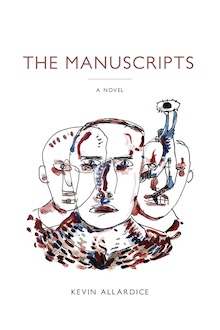

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Kevin Allardice writes about The Manuscripts from What Books Press.

+

Two Tributaries: Creative Writing and Phenomenological Practice

In the 1969 postmodern Victorian novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Fowles frequently positions his characters at historical junctures they’re ignorant of, inviting us to consider how this or that twitch of neurosis could anticipate the century to come. As habits of narrating become habits of reading, we begin searching for each prescient gesture. When the gentlemen naturalist Charles contemplates his potential betrayal of Sarah, the social pariah with whom he has become infatuated, Fowles’s narrator tells us that even though Charles is thinking of “her,” what comes to his mind is “not a pronoun, but eyes, looks, the line of the hair over a temple, a nimble step, a sleeping face” (Fowles 332). The progression of that sentence enacts a common creative writing exercise: unpacking the bit of insufficient language to find and enumerate little precisions of sensation that better illuminate experience. It’s a process of defamiliarization. When the familiar language flatlines, it’s the details, rendered new and curious in their particularity, that defibrillate, galvanize, teach us—and, briefly, Charles—how to notice.

And yet, it isn’t the language of defamiliarization and associated modernist preoccupations—“Make it New!”—that constellate around these characters; there are other twentieth-century movements that Fowles suggests Charles and Sarah anticipate from their Victorian chrysalis. Two pages earlier, when Charles is itemizing the furniture around him, Fowles’s narrator notes that Charles’s experience of his surroundings is the “opposite of the Sartrean experience,” contrasting how existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), a century later, would see alienation where Charles finds comfort (Fowles 320). Indeed, it’s existentialism that more explicitly frames, even by contrast, how these characters experience their subjectivity. It can be helpful, then, to consider Charles’s unpacking of the pronoun “her” into the sensorial particulars of how he perceives her, not as an illustration of defamiliarization, but as a practice more firmly rooted in existentialism’s antecedent, phenomenology.

Charles’s descriptive process aligns with what phenomenology’s progenitor, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), might have called bracketing. In phenomenological bracketing—which Husserl developed from what the ancient skeptics called epoché—we isolate an object from preconceived ideas, reducing it to the various ways it presents itself to our consciousness: an atomized and itemized account of how object encounters subject. That’s not an ice cube in your palm; it is hardness, it is slipperiness, it is coldness so intense it becomes painful, until it is the numbness at the center of your palm, soon a puddle. The purpose is to recognize how the ways we’ve learned to see, to sense, have alienated us from essential truths of experience, and then to reconcile that alienation, with descriptive language as the traction. The ambitions of defamiliarizing are remarkably similar, if not identical. Perhaps, then, it is misguided to pit defamiliarizing and phenomenological bracketing against each other; perhaps it’s more instructive to consider the ways the development of creative writing pedagogy, distinct from modes of writing mentorship outside the academy, corresponded with the development of phenomenology, to consider the possibility of a shared root system, to consider the possibilities of how the two disciplines might better inform each other today.

The received histories of creative writing and phenomenology have been siloed away from each other. But it was the possibility of their common origins that first offered me an entry point into what became my new novel, The Manuscripts. In the novel, an unnamed philosopher hires an art student to chaperone him around the countryside, helping him pass through guarded checkpoints to retrieve manuscripts he hid during a recent war. Although it’s the fraught relationship between Martin Heidegger’s particular phenomenology and fascist ideology that pulled me into the story, it was the realization that Heidegger’s predecessor, Husserl, conducted “labs” (rooted in this practice of bracketing) that were oddly resonant with generative writing workshops (in which a combination of constraints and stimuli help participants create produce new work, exercises often rooted in defamiliarization) that opened the door.

The genealogy of creative writing as a pedagogy was traced most notably by Mark McGurl in his 2009 study The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. McGurl locates the germination of creative writing pedagogy in the progressive education theorized and advocated by John Dewey, “for whom ‘mere activity’ in the world does not count as authentic experience” until it is reflected back to you (McGurl 86). Since how one comprehends experience is foundational to the authenticity of that experience, how we record experience shapes that very experience; the autopoetics of writing, McGurl points out, is a constituent part of the very experience it records. Dewey’s theories eventually dovetailed in practice with those of Russian formalists like Viktor Shklovsky, who saw “art as a means for restoring perception of the world” and famously wrote that art’s technique “is to make things ‘unfamiliar’”—that is, to defamiliarize (Crawford 212; Waugh 216).

But, while McGurl traces how Dewey’s progressivism contributed to the development of the New Criticism that “put the point of view of the artist at the very center of postwar literary studies,” helping make the creative writing workshop a staple of English departments, Joseph Darda, in “The Philosophy of Creative Writing,” argues that actually “the discipline grew out of a conservative backlash to progressive education” (McGurl 133; Darda). Specifically, he locates its origins in the reactionary doctrine of New Humanism, the seeds of which were planted by English poet and critic Matthew Arnold (1822–1888). Darda argues that the philosophy of creative writing “is a philosophy of disciplined individualism, of crafted authenticity,” which “opposed deterministic theories of human nature” (Darda).

No matter the vector—Babbitt or Dewey, or a double helix of the two—the shift in academia to giving novelists and poets offices and tenure marked an institutional turn away from the philology that had dominated academic literary study in the nineteenth century, which saw itself as an exact science (Myers 23-24). Within the framework of philology, the study of literature was a means to understanding or explaining arenas already valued in more established fields; the fact that fiction and poetry were the conduits for these insights seemed arbitrary. The academic discipline of literary studies, then, seemed designed to cultivate a tacit skepticism of literature’s intrinsic value, not cultivate literary practitioners.

Philology’s aspirations to the legitimacy of the hard sciences aligned with the domination in the academy of scientific naturalism, which found broad application of scientific methods in the humanities. It was in this intellectual milieu that Edmund Husserl, a Jewish-born Austrian-German, switched his course of study from mathematics to philosophy, and by the turn of the twentieth century he’d been promoted from privatdozent (essentially an unpaid adjunct instructor) to salaried professor. Decades before the rise of Nazism ended his career and enshrined Heidegger’s, Husserl commanded a devoted cadre of students and taught them how to lance the membrane between perceiving subject and perceived object. In his philosophy of phenomena, it’s the act of description—of noticing, rigorously, in language—that allows us to understand the nature of lived experience.

Carving out this design and methodology, Husserl opposed the ways that dominant modes of inquiry seemed to remove the act of perceiving from our understanding of what is perceived. But in challenging the humanities’ over-reliance on scientific methods, he did not reject evidence; rather, he was challenging what we thought constituted evidence. He wrote, “Every type of first-hand intuiting forms a legitimate source of authority” (Sinha 12). In order to authorize first-hand experience, “a new way of looking at things is necessary” (Natanson 13).

Founding the Freiburg Phenomenological Society in 1918, Husserl mentored, amongst others, Edith Stein, Karl Löwith, and Martin Heidegger (whose writing would wind up in the hands of Sartre years later, animating French existentialism). Much of the student labor that these Freiburg “laboratories” fostered was enacting this “new way of looking at things” (Bakewell 39). The new way came from an old way: Epoché. Developed and coined in the third century B.C., epoché is a suspension of suppositions. While epoché was initially intended to help the practitioner achieve a state of equanimity, Husserl developed it further as a heuristic; this was phenomenological bracketing. We can only understand phenomena for how they encounter our own subjectivity, and rigorous descriptions of those encounters (this screen a flat, bluish light) might reveal all that we often take for granted (the light pixelated with tiny Lego-like geometry), the sensorial details that tend to be obscured by our daily need to economize our perception (the rigidity of pixels proliferating into elasticity). According to Viktor Shklovsky, defamiliarizing requires disrupting the economy of perception.

John Fowles begins the final chapter of The French Lieutenant’s Woman with two epigraphs. The second of which is from Matthew Arnold: “True piety is acting what one knows” (Fowles 461). About this epigraph, in the novel’s penultimate paragraph, Fowles’s narrator reflects that a “modern existentialist would no doubt substitute ‘humanity’ or ‘authenticity’ for ‘piety’; but he would recognize Arnold’s intent” (Fowles 466-467). In facilitating a hypothetical dialogue between “the modern existentialist,” the inheritor of Husserl’s phenomenology, and Matthew Arnold, a disgruntled and estranged potential forebearer of creative writing pedagogy, Fowles accomplishes far more elegantly what I am attempting to do here: a gesture at the shared source of two tributaries. Indeed, as Fowles suggests, the language might have shifted, but they—and we—can recognize the shared intent.

+

Works Cited

Bakewell, Sarah. At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails with Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty and Others. Other Press, 2017.

Crawford, Lawrence. “Viktor Shklovskij: Différance in Defamiliarization.” Comparative Literature, vol. 36, no. 3, 1984, pp. 209–19. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1770260. Accessed 15 Nov. 2023.

Darda, Joseph. “The Philosophy of Creative Writing.” Los Angeles Review of Books, 25 February 2019, https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/philosophy-creative-writing/. Accessed 14 November 2023.

Fowles, John. The French Lieutenant’s Woman. Little, Brown, 1998.

Natanson, Maurice. Essays in Phenomenology. Germany, Springer Netherlands, 2013.

McGurl, Mark. The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. Harvard University Press, 2011.

Myers, David Gershom. The Elephants Teach: Creative Writing Since 1880. Prentice Hall, 1996.

North, Michael. “The Making of ‘Make It New’.” Guernica Magazine, 15 August 2013, https://www.guernicamag.com/the-making-of-making-it-new/. Accessed 16 November 2023.

Sinha, D. Studies in Phenomenology. Springer Netherlands, 1969.

Waugh, Patricia, editor. Literary Theory and Criticism: An Oxford Guide. Oxford University Press, 2006.

+

Kevin Allardice is the author of five previous novels. He earned an MFA from the University of Virginia and more recently received a Jack Hazard Fellowship from the New Literary Project. Originally from California, he now lives with his family in Iowa City, Iowa.