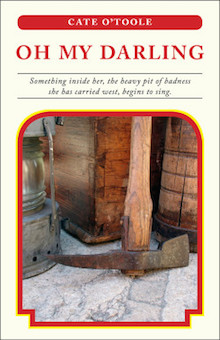

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Cate O’Toole writes about Oh My Darling from Black Lawrence Press.

+

Oh My Darling began with a truly bad reality show called Gold Rush. The Discovery Channel aired the first episodes in December 2010 — they called it Gold Rush: Alaska at the time, as though already planning to mine a series of spin-offs — and I must have started watching it soon after. My boyfriend was a fan right away, and I made a general nuisance of myself by loudly criticizing the show. While he was content to spend an hour watching a group of inexperienced nincompoops tear Alaska to shreds in their lust for gold, I railed against their stupidity, their poor decision-making. Every time one of the characters wiped a hand across his dirty, sweaty face and stared into the distance, my rage intensified. Every time someone said, “I just don’t understand,” or blamed bad luck for their latest entirely preventable disaster, I stomped around our apartment and shouted at the TV. My boyfriend lovingly asked me to find another outlet, perhaps one that didn’t involve quite so much yelling.

Oh My Darling began with a truly bad reality show called Gold Rush. The Discovery Channel aired the first episodes in December 2010 — they called it Gold Rush: Alaska at the time, as though already planning to mine a series of spin-offs — and I must have started watching it soon after. My boyfriend was a fan right away, and I made a general nuisance of myself by loudly criticizing the show. While he was content to spend an hour watching a group of inexperienced nincompoops tear Alaska to shreds in their lust for gold, I railed against their stupidity, their poor decision-making. Every time one of the characters wiped a hand across his dirty, sweaty face and stared into the distance, my rage intensified. Every time someone said, “I just don’t understand,” or blamed bad luck for their latest entirely preventable disaster, I stomped around our apartment and shouted at the TV. My boyfriend lovingly asked me to find another outlet, perhaps one that didn’t involve quite so much yelling.

At first I just stewed. I thought about the wives those men had left behind, rarely mentioned but always referred to as “my wife” or “the wives,” and only appearing on-screen to say goodbye and wish their men well. I thought about those nameless, faceless women who were left behind to hold their families together while their husbands set off to gamble their futures and make a giant mess of things. From there I found Clementine, miner’s daughter. She’s an object of ridicule in the folk song, big-footed and clumsy, and I wanted to take her seriously.

I knew the basic outline of the song, but hadn’t realized until I started reading up on it that there are about a million alternate endings, a verse for every occasion. The Boy Scouts have a verse, as does the Red Cross. In one, the narrator is revealed to be her father, humorously recounting all of her failures, bemoaning how unsuited she was for the mining life. In another, the song is narrated by her lover and he closes with the announcement that he’s over her loss and moving on to her sister. The words “oh my darling” are repeated again and again, but Clementine didn’t seem to be dear to anyone. She was a story men passed back and forth to each other with a grin and a shrug.

The character of Clementine was easy: I felt like I knew her as soon as I sat down to write. My trouble was deciding how to shape the story; with so many options to choose from, they all seemed intriguing and incomplete. Taking a cue from the song once again and structuring the collection as a series of choose-your-plot stories was the obvious, ideal solution. I could explore as many sides of Clementine as I wanted. I could hold her up to the light and still be free to investigate the dark, secret twists of her heart.

That darkness was important to me. Another television show, near and dear to me during my childhood, followed a woman’s journey on the Colorado frontier, highlighted her struggles and triumphs. But the eponymous Dr. Quinn, with the exception of one or two short-lived storylines, was never in real danger. At worst, she would suffer through forty minutes of unpleasantness and then everyone would learn a lesson, thank God and hug it out. As a child, Dr. Quinn seemed a brave and unflinching adventurer; rewatching the series as an adult, I’m struck that she doesn’t even seem to get dirt on the hem of her long, full skirts.

To be blunt, I wanted to put Clementine through some shit. Though I was more than 150 years removed from the Gold Rush, I imagined the two of us would fear similar things: abuse, neglect, abandonment, trauma. I spent a lot of time thinking about what scared me, and making Clementine face it — and then, sometimes, letting her come out the other side.

I did a small amount of real research on a select few details. I looked at old maps of California and traced out a route I thought Clementine might take, settled her in an area where a mining camp had been. For some reason, I became obsessed with knowing what her geese might have looked like, and researched the histories of breeds of geese, tried to piece together exactly what sort of goose might show up in Northern California in the mid-nineteenth century. I studied old photographs of San Francisco and the mining towns that dotted the hills. I sprinkled a fine layer of grime over everything.

Mostly, most importantly, I read. I revisited texts from my graduate school classes, narratives about women’s journeys across the plains. I reread Willa Cather’s O! Pioneers, devoured as much Angela Carter as I could get my hands on. Somewhere in there I read all five of George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire tomes — talk about putting your characters through some shit — and when I needed an escape I picked up romance novels about cowboys and unpacked them on my blog. I read Astray and Don’t Bet on the Prince, I read Charles Frazier and Leif Enger. I read Bonnie Jo Campbell’s Once Upon a River and Gil Adamson’s The Outlander. I surrounded myself with fierce, beautiful characters and let Clementine marinate. Eventually, we found our way.

+++