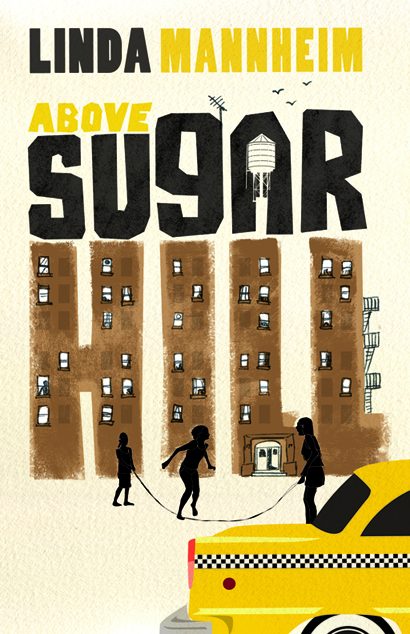

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Linda Mannheim writes about Above Sugar Hill from Influx Press.

+

In 1995, I became obsessed with an unsolved murder case. Bruce Bailey had gone missing in 1989. A newspaper article from that time told the story of how, on the 14th of June that year, he said goodbye to his wife and child and then walked out to the streets of Manhattan, failing to make it to either of the meetings he had planned for that evening. Days later, his legs, arms, and torso were found in plastic garbage bags on a sidewalk in the Bronx.

In 1995, I became obsessed with an unsolved murder case. Bruce Bailey had gone missing in 1989. A newspaper article from that time told the story of how, on the 14th of June that year, he said goodbye to his wife and child and then walked out to the streets of Manhattan, failing to make it to either of the meetings he had planned for that evening. Days later, his legs, arms, and torso were found in plastic garbage bags on a sidewalk in the Bronx.

Bailey was a housing activist: he organised tenants in some of New York’s poorest neighbourhoods, in buildings where nothing was ever repaired, where roaches ran rampant and the winters went by with broken boilers refusing heat.

I had grown up in a building like that, in Washington Heights, one of the neighbourhoods where Bailey had organised tenants. And, after 15 years in rural New England, I’d returned to New York with a yearning for the chaos and confrontation of my home town. This time, I moved to gentrifying Brooklyn, to an apartment in Park Slope with a tiny room across a communal hall where I wrote and researched and tried to understand what it was that had made New York the place it had been when I’d fled.

I wanted to understand no go zones, streets devoured by arson, unheated buildings with walls weeping condensation — the decimation of what was once the city’s working class neighbourhoods. I was carrying out a vague kind of exploration. Between rapid transit and temp jobs, during the year I returned, I read The Epic of New York City and The Power Broker, City for Sale and We’re Still Here. But I wanted more information than that. And, in those days before Google, I found it through an early online database, LexisNexis, which charged hundreds of dollars for subscriptions, but was free for law students, one of whom shared his login details.

In the tiny room across the communal hallway, I plugged in my search terms:

Tenant rights

Rent strikes

Tenant organizers

And that was how the story of Bruce Bailey blossomed before me, through an article headlined: ‘Who Killed Bruce Bailey?’

Bruce Bailey had made many people angry. He was known for being the most confrontational of the tenant organizers: quick to organize a rent-strike, accused of corruption by other activists, investigated by New York State’s Charities Bureau. But the police, his family, and other organizers agreed: a landlord had to be behind his murder.

The tiny room where I wrote overlooked a school, and at three o’clock, a cacophony of children’s voices rose and filled the street. By 3:30, they were all gone, and the street was silent again.

I logged into LexisNexis almost every day through a dial up connection (the music of touch tones, the static of the long in, the quiet of a successful connection).

There were other stories that intrigued me, but I couldn’t get the story of Bruce Bailey out of my head.

And one day the story ‘Tenor’ came to me about a community activist who goes missing. It was indeed inspired by the real life story of Bailey’s disappearance, but Tenor, the fictional (and absent) protagonist lived a different life than Bailey’s. The name Tenor came to me out of nowhere, a nickname for a former student activist, because… Well, I decided, he must love opera. And his story is told by a circle of fictional acquaintances, each of whom answers questions posed by journalist, who only speaks herself in the end.

Almost twenty years later, living in London, I revisited ‘Tenor’ as I was going over the proofs for Above Sugar Hill, a collection of stories set in the neighbourhood where I grew up. Many of the stories grew out of other research that I did at the time. But ‘Tenor’ was the story I was most nervous about. Though the story was fictional, the violence at the heart of it was not. What would it be like to look at news stories about Bruce Bailey now? And had the murder ever been solved?

I plugged my search terms into Google. An article from New York Newsday surfaced, headlined: ‘Who Killed Bruce Bailey?’

This was, indeed, the original article that had obsessed me when I’d first come across it in 1995. I had no trouble seeing why. “In a steamy loft upstairs from a bodega on West 106th Street,” the article began, “tenant activist Nellie Bailey sits in the offices of the Columbia Tenants Union, chainsmoking Merits and flipping feverishly through her husband’s appointment calendar, looking for a clue.”

It read like a novel, hard-boiled as Hammett. Who wrote this? I stared at the byline. It was DD Guttenplan, the London correspondent for The Nation, who I’d gotten to know since arriving in London. I emailed him and sent him a copy of ‘Tenor.’

“The funny thing” he wrote back, “is that if you had written to me as recently as six months ago I could have (and would have been delighted to) given you Bruce Bailey’s 150 page FBI file, which I requested via FOIA when he was killed.”

Since then, we have met and talked about the story — on a Resonance FM show on New York City and gentrification. Sometimes, someone asks you something in a setting when you have to come up with an answer, and because you have to say something, you find yourself telling the truth. I had to explain, finally, why the story of Bruce Bailey was so compelling to me. And I realised that, in the original article he wrote, Don had articulated something about the brutality of that time and that place that I found myself at a loss to explain. It had been impossible to explain to the people I’d met in rural New England. And it wasn’t spoken of with other people who’d lived through it either.

The research for ‘Tenor’ arrived before the story did, and with it a way to show what life in parts of New York had been like in the 20th Century — the day to day hustle of life in buildings that were milked for profit, and the violence that was always nearby there and sometimes alighted.

+++