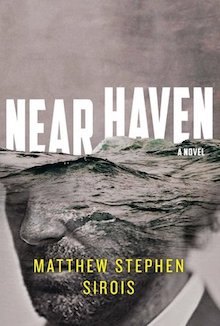

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Matthew Stephen Sirois writes about Near Haven from Belle Lutte Press.

+

Two men sit on a wooden pier, smoking, discussing a light in the sky.

Eight years ago, this image fell toward me like a fly ball. I’d just finished drafting a shitty “practice novel” that I knew was inedible cellulose before the printed pages had cooled. There was no formal education behind my work; I’d barely mustered the faith to finish high school, and had fallen directly into a routine of manual labor, casual substance abuse, and obsessive reading. It was all very typical, and I knew that. Knock-off Mickey Rourke playing knock-off Bukowski. A general familiarity with the Western canon was evidenced in the beaten paperbacks littering my apartment, but I hadn’t found the entry point into my own “oeuvre.” Melville, Faulkner, O’Connor — I felt like a sports fan, full of admiration but impossibly far from his heroes. Turning to slightly more contemporary fare, I began my Cormac McCarthy years. Suttree and Blood Meridian were megalithic; I was thrilled by their specificity of vision, the assurance of those baroque sentences. They were inspiring. But it was The Road, with its one foot planted in the Bible and the other in a zombie flick, that seemed to be my invitation to play. The first genre-crossover hit from the literary Big Leagues to have dropped into my waiting hands.

So, who were these men on the pier? I knew they were both firmly working-class, Steinbeckian, and yet very much individuals. That their speech was rough and grouted with expletive. I understood that they would discover their own agency through some grand, external, and fabulist threat. The source text for this project was apocalyptic — after all, I was writing in the golden age of the apocalypse novel — but somehow these characters would both occupy and defy that genre, challenging Bible and zombies alike.

I bird-dogged these fictional men for two years, amassing a meandering draft of 150 pages, but the story was choppy and obscure. A parallel narrative about the French and Indian War was clinging to the 20th century storyline like a lamprey, and the characters phased in and out through floating vignettes. I needed structure. My wife — girlfriend, then — signed me up for a ten-week class at the Richard Hugo House, a community writing center in Seattle. I balked, initially, arguing that I would never be a good student. Nevertheless, I’d finish up at my restaurant job on those ten consecutive Thursdays, knock down two bourbons and a Highlife, and go to class. The blue-collar chip on my shoulder made me a terrible workshop participant, but I gleaned a lot from the professionals who wrote and taught there. Avoid adverbs, maintain the active voice, learn to write a cover letter. Conflict, conflict, conflict. I found I was not, in fact, an iconoclast who could afford to shit all over the established principles of craft. I discovered that writing was a business, and that one could move forward by taking their art seriously and using small successes to build larger ones.

A friend leant me Alan Weisman’s The World Without Us, because I was writing some vague species of apocalyptica, and what stuck with me was a description of the ancient Turkish city of Aydintepe: discovered in the late 1980’s, this underground network of tunnels and chambers was carved from porous volcanic rock, about a kilometer in diameter, and fifteen feet under the surface. Complete with a water supply and massive stone doors to block its few entrances, Aydintepe resembles nothing so much as a gigantic Late Roman fallout shelter.

I knew that the men on the pier were bracing themselves for something they perceived to be catastrophic. The ancient Turks had left us this astounding reminder that human industry serves our fears, perhaps more often than our aspirations. That notion of self-condemnation being industrialized — and our human tendency to believe the sky is falling — became central themes of Near Haven.

I’d also uncovered, down in those red-walled catacombs, a working analogy for my own process. Many writers made outlines; they had their transitions and distance markers laid out in advance like triathletes. Zadie Smith and others have talked about writing in terms of building a house, illustrating the difference between macro- and micro-planners, but even this does not quite resemble my zero-planned process. Rather than building, or filling empty space with a predetermined checklist of stuff — the approach which had led to my plot-heavy but sterile practice novel — I seemed to be excavating this new work from a substrate of memories and sensory input. The story was like a cavern I would enter — separate from my actual life, but made of the same material. Each day, I’d lower myself into the hole with a lantern and a pickaxe, seeking to expand it, and never fully certain what lay ahead in the darkness. The apocalyptic theme became its long, central corridor, and my adolescence in Maine a kind of plaza from which tangential avenues began to branch, complicating my subterranean world with whims and obsessions. The Hall of Political Musings. The Catholic Upbringing Pavilion. The Museum of Fishing Stories. Of course, I tried to do too much. Sometimes I would chase an idea for weeks — a discussion of the “harvest moon” optical effect, for instance, or an essay on the paintings of Andrew Wyeth — only to find I must dynamite this unstable passage for the good of the whole.

I can’t exactly recommend my own methods — forgoing an education and failing to plan ahead are not “methods” — but, were it not for the aggregated results of constant trial and error, I wouldn’t have produced the layered, personal narrative of Near Haven. From countless hours spent in commercial kitchens and industrial shops, to experiences of birth and death, and including all the art, culture, and political seismography of nearly a decade, the data set for this book was the life I lived during its creation. In that time, I deleted more material than I saved — easily two additional book-lengths — and what did make the cut would surely be unreadable if it hadn’t fallen into the hands of several intelligent editors. Professionalism, for me, meant learning how to find these people and accept their help.

To some degree, this book was a rebuttal. Not just to end-of-the-world narratives, but also to my father’s maxim of, “Go along to get along.” I once wanted to show him I could snub the world and still create something of value to it. If he’d lived to see Near Haven’s publication, he’d be happy that I’d learned to negotiate with the world, bit by bit, as I dug my way through it. Our dynamic found its way onto the pages, as I realized the strange light above the pier was, of course, just a symbol meaning “life.” And those work-hardened men — one of them difficult to upset and the other impossible to please — were arguing, naturally, about what it meant.

+++

Matthew Sirois was born and raised in midcoast Maine. His fiction and essays have appeared in The New Guard Review, Necessary Fiction, Split Lip Magazine, and The Ghost Story, among others. He attended the Richard Hugo House Master Class in Prose (Seattle, 2012) and The Writer’s Hotel Master Class in Fiction (NYC, 2015). Matthew has read for audiences in such venues as the Rendezvous, Seattle, and KGB Bar in the East Village. Matthew lives in western Massachusetts with his wife and daughter.