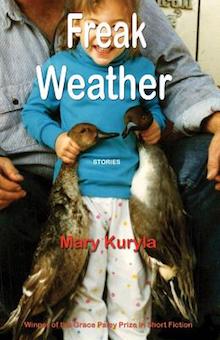

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their process for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Mary Kuryla writes about Freak Weather, winner of the Grace Paley Prize in Short Fiction from University of Massachusetts Press.

+

My collection Freak Weather Stories won the 2016 Grace Paley Prize and was published by Massachusetts Press this November. A few of the stories that wound up in the collection had previously been adapted into films. While most short stories are adapted and made into films in a rather straightforward, linear path, my process with regards to the adapted stories was unusually circular, moving from the page, to the screen, and back again to a revision of the original story. This cyclical, iterative workflow has had a profound impact on how I now write and revise.

Allow me to explain: “Freak Weather” is the first story in my collection and it also gives the collection its name. In addition, the story served as the foundation for a feature film that I wrote and directed, and which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. Indeed, I was inspired to make the film based on the heated controversy at numerous literary magazine editorial meetings where “Freak Weather” had been submitted. I knew that this much heat over the bad behavior of the story’s main character, Penny, would make for a strong cinematic experience, and indeed, the completed film also generated a good amount of controversy. However, here’s the important part: having gone through the process of rehearsing with the film’s actress (Jacqueline McKenzie), hearing the lines spoken and the actions embodied, followed by shooting and editing the film, then viewing it on a big screen with large audiences, I was able to witness the gaps and inconsistencies in the original story. I could see where I had failed Penny, where I had stifled her as a result of my own failure of courage. As a result, I returned later to the story with absolute clarity and revised it based on this experience of seeing it performed and rendered onscreen.

Two additional short stories included in Freak Weather Stories (“To Skin A Rabbit” and “My Husband’s Son”) were also previously made into films, though with different directors. To a lesser extent, I was able to improve on these stories, as well, after having the lucky opportunity to see them adapted into short films. The dramatic requirements of a film adaptation can tell you a great deal about the original story; the act of adaptation into another form carries light into corners that were underdeveloped or insufficiently dramatized in the original. It is worth noting that the great Swedish theater and film director Ingmar Bergman often produced short stories, novels, and plays, which served as early incarnations of his screenplays. Working in these diverse genres was a fluid process for Bergman; they supplied various ways to inhabit the words.

A couple of years ago my work was selected for the New Short Fiction Series, the longest running spoken-word event in Los Angeles; as a result, five additional stories in the collection were performed on stage by actors. Having the opportunity to closely observe the ways in which the stories held the attention of the audience — or failed to hold that attention — I was able to discern where I had included too much detail, or where information had been elided, resulting in confusion. These dramatic performances taught me how to whittle down a story to its essence, paying serious mind to leaving no doors open through which my audience might exit. Many standard narrative tactics came into question in the context of a performed short story, including the extended metaphor and the flashback. Flashbacks are particular liabilities when the story is performed; one can feel the flagging of audience attention as the story drifts away from the mounting crisis of the present story into an alternate world that is all to often only expository in nature. In other words, the flashback offers subtle permission to the audience/reader to take a break, an exit sign out of the story’s drama.

Improved narrative tactics were not the only thing that that came into view. My whole collection came into view as a result of these spoken-word performances, an unexpected gift. The opportunity to see my stories performed by talented actresses supplied external and verifiable proof that my strange, wayward, and futilely undaunted characters could hold an audience’s attention, especially if the craft of my storytelling was tight. Of course this is hardly new knowledge in the world of performed literature; Charles Dickens’ passion for acting and the stage taught him a great deal about holding the reader’s attention. Who of us cannot name at least one character invented by Dickens? You can almost hear the creak of the boards beneath Oliver Twist’s or Scrooge’s feet, as if they carry the breath of the stage right onto the pages. They are characters in every sense of the word.

Though often laborious, and certainly constraining, I would not have it any other way. Even when I do not have the great good fortune of seeing my work made into films or performed on stage, I nevertheless always at some level make that possibility a requirement of the sentences’ visualization and vocalization. The language must maintain a physical quality that is not just cinematic, as people like to call it, but actually visible: this is done in consideration of how the letters place in the words, the placement of the words in the sentence, and the sounds the words elicit. “By the mouth for the ear,” as the late William Gass said.

Gass also said, “It is not the word made flesh but the flesh made word.” Can the word so transcend what it represents that it becomes a thing, a flesh, an object in its own right? Ask any actor, and they will tell you that the body is the actor’s tool. My question is: why shouldn’t the body be the writer’s tool, as well? Seeing one’s work performed by actors is an exhortation to get up off the chair and feel the emotion one is evoking on the page, locate where this emotion situates in the body, move about to discover what your body will do to either embrace or cast off that emotion.

I think of these processes as a kind of code switching. As a story moves from the page to performance, it moves from one domain to another. The requirements of performance are fundamentally different from those of writing. The magic happens, however, as the performed story returns to the page, bringing with it the elements that made it flourish onstage.

+++

Mary Kuryla’s stories have received The Pushcart Prize, as well as the Glimmer Train Very Short Fiction Prize, and have appeared in Epoch, Shenandoah, Denver Quarterly, Witness, Greensboro Review, Pleiades, The New Orleans Review, Copper Nickel, The Normal School and, for the third time, in Alaska Quarterly Review. Kuryla’s award-winning shorts and feature films have premiered at Sundance and Toronto. She has written screen adaptations for John Malkovich at Mr. Mudd Films, United Artists and MGM. Kuryla has been a scholar at New York Summer Writers Conference and a Margaret Bridgeman Scholar in Fiction at Bread Loaf.