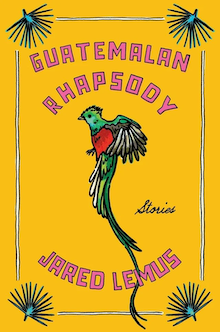

Ranging from a custodian at an underfunded college to a medicine man living in a temple dedicated to San Simon, the patron saint of alcohol and cigarettes, the characters in Jared Lemus’s Guatemalan Rhapsody (Ecco Press) find themselves at defining moments in their lives, where sacrifices may be required of them, by them, or for them.

In “Saint Dismas,” four orphaned brothers pose as part of a construction crew, stopping cars along the highway and robbing anyone foolish enough to hit the brakes. In “Heart Sleeves,” two wannabe tattoo artists take part in a contest, where one of them hopes to win not only first place but also the heart of his best friend’s girlfriend. And, in “Fight Sounds,” a character who fancies himself a Don Juan is swept up in the commotion of an American film crew shooting a movie in his tiny town, until the economic and sexual politics of the place are turned on their head.

Across this collection, Lemus’s characters test their loyalty to family, community, and country, illuminating the ties that both connect us and constrain us. Guatemalan Rhapsody explores how we journey from the circumstances that we are forged by, and whether the ability to change our fortunes lies in our own hands or in those of another. Revealing the places where beauty, desperation, love, violence, and hope exist simultaneously, Jared Lemus’s debut establishes him as a major new voice in the form.

“Jared’s kaleidoscopic debut is a glimpse into Guatemala through stories that hit deep emotional notes. Heavy in some places, buoyant in others, Lemus’ writing is never without tenderness, even in the most gutting moments. The characters throughout leap off the page, challenging our emotions at every turn, while illuminating everyday struggles through a powerful lens. This captivating short story collection will leave you feeling all the feels. It’s not to be missed.” — Cebo Campbell, author of Sky Full of Elephants

Jess Maxwell spoke to Jared Lemus about growing up in poverty, the alienation he felt about being a first-generation child of immigrants, seeking out the musicality of prose, and discovering the complex beauty of Guatemala.

+

Jess Maxwell: I’m always interested in learning a little about writer’s lives in their youth, when maybe writing was only an idea. What was your early life like and how did you find yourself turning to writing?

Jared Lemus: My first memories are of living in a little trailer park near Geyer Springs Road in Little Rock, Arkansas. It was a tiny space with no heating in the winter and no air conditioning in the summer; I think this is when I began telling myself stories: I wasn’t freezing, I wasn’t hungry, that wasn’t a bullet hole a cop shot through the wall chasing someone through the complex. Middle school wasn’t much better, but it was at the very beginning of my senior year of high school when things began to get worse. I left home over religious differences with my parents, and have just kind of been on my own ever since. After high school, there were times where I was living in my car, or like, living on the street, and, really heavy into drug use, and, I don’t know, something about it, I think, the suffering, and all of the substances rewired my brain. There’s a “Hunter S. Thompson-ism,” right, where he says: “I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me.” I don’t believe that now, but I did then. So, now, it’s more of a regret but I can’t deny the change in brain chemistry or in life trajectories. Originally, I wanted to be a musician, but again, I was always messed up and unreliable at practices, just like my bandmates. And so, writing was that solitary thing I could do where I wasn’t depending on anyone else. It was either I showed up and I did the work, and if I didn’t, it was on me. I guess that’s the answer, it’s essentially, I gave up on music, and I decided to write instead. I gave up music for music on the page.

JM: Ah, yes. “Music on the page.” The perfect segue to talk to me about the title and the stories within your collection, Guatemalan Rhapsody. How would you describe them? When I think of a rhapsody I think of wild, unstructured beauty whether it be in music or poetry.

JL: You know people talk about immersion in stories as they read them? What pulls me in is the language, it’s because it feels like I’m listening to an album. Sometimes I’ll read something, and I’ll be like, damn, that’s a good sentence, or that’s a good paragraph or that’s some good line-by-line writing. It’s almost a song, and like a song, what distinguishes one story from another is each writer’s unique voice, right? When I write, I have no idea where I’m going. I have no idea what the story is going to be about. I just start with that first sentence, and then I just rewrite it and rewrite it until it sounds good. Then from there I write the next sentence. And then I make sure those two sound good together. If the prose doesn’t sound really beautiful, I’m not as invested in the story and I don’t get lost in listening to it. So, part of it is that, and the other part is that these are stories for and about the people of Guatemala. That’s where I spent a lot of my childhood. These characters are a rendition of many of the people I knew. My parents, my brothers, friends, enemies in Guatemala, schoolyard fights with other boys. It’s a compilation of all these people all put into different situations. So, the characters, they’re real, the stories are what’s made up.

JM: One of the things that I found especially compelling about your characters is how you captured this liminality of identity. Many of the characters are immigrants who are either brought by their parents or came to the United States, believing they could have a better life, but are left fractured, trapped between cultures.

JL: My parents were immigrants here. I’m first generation born. English wasn’t my first language. I didn’t learn English until I was five. I was in a school, an American school, and people didn’t understand me, and I didn’t understand them. I could have grown up in any country in the world, but at home it would have still been Guatemala. I didn’t ever think of myself as weird or different or anything like that until I started going to English-speaking schools and all of a sudden it was like, oh people don’t do this, or people don’t do that, or they don’t eat this food, or they have these specific traditions. Even now, I find myself in moments where I’m like, oh that’s an Americanism I’ve never heard or don’t understand, and I’ve lived here almost my entire life. That’s the truth I know, so those are the stories I try to portray: those of these characters who maybe don’t quite fit in with their surroundings or society or friends but always remain true to themselves.

JM: Could we return to what you were saying about addiction, drug use. I feel like many, if not all your characters are struggling with some kind of darkness, a haunting past or addiction. Despite that, your stories also offer this shift, or glimmer of hope for these characters. A word that kept coming to my mind as I was reading was redemption. Do you agree with my assessment, and do you believe in redemption?

JL: Actually, I really do. I think that a lot of people who’ve read my stories are just like, oh, these are really dark. And I’m like, I don’t know if they’re dark, I think they’re real and true. Most of them end on a happy note. And you’re right, there are moments of hope. For example, in “Bus Stop Baby” we have a character who is addicted to heroin, but someone offers him a way out. The question becomes: does he take it or does he let the addiction take him? And, I think, I hope, the reader cares enough about him to really hope that he finds the next bus stop—something better. So, yes, there’s a lot of drug use in my stories but it’s not because the characters are bad or anything like that. It’s just like they find themselves in an inescapable loop. The same loop that many people, many Americans especially, find themselves in. We’re all suffering through this life in some way. What are we going to do to cope? Some people go to the gym and some people shoot up. My characters reflect those who choose the latter.

JM: I feel like you really shined a light on the ambivalence of the American dream with this collection. As I said before, many of your characters were either brought here or came to America thinking that they were going to have a better life, but in fact, found themselves caught in something far more complicated and wondering if it really is better.

JL: Yeah, exactly I found that to be the case in “St. Dismas,” right? These brothers are displaced from their home, and they have this really terrible life in Guatemala. Alternatively, there is also Santorío in “Whistle While You Work” who’s cleaning the buildings at a college in the U.S. after immigrating from Guatemala and even though he’s not addicted to anything, his life here really sucks. His job is terrible, and he lives paycheck to paycheck. He can’t really afford food, barely has any furniture, but he still tries to find love. These stories have different types of struggles but nevertheless struggle.

JM: I’m glad that you brought up “Whistle While You Work” because it was my personal favorite story in the collection. What is your favorite story in this collection and why?

JL: That’s so funny. I always hear “Whistle While You Work” is people’s favorite. For me, I’m partial to the opening story, “Ofrendas.” I think it’s because it’s the one I wrote most recently, but it really did feel like it was somehow being offered to me and I was just writing it out, like I was communing with the Maya gods. I had candles lit. I went to one of the temples of San Simón before and I have a few of his artifacts and I had them around and I was writing and it just felt different from some of the other stories where I had to work and rework that one sentence. With “Ofrendas,” I essentially wrote the first sentence and I was like, damn that’s a good fucking sentence and then I just kept going; it felt like I was merely a vessel receiving these words from on high.

JM: Of all your characters, which do you feel most connected to?

JL: I love them all, but I think I’m going to defend “Heart Sleeves” while I’m here. Those boys if they could, would just hold each other all night, but they’re so full of machismo that they can’t admit they care and have love for one another, so they hurt each other instead. They’re a product of everything that we see happening now that drives all this, “I’m an alpha, you’re a beta male” talk. It’s their inability to truly express love for another person or friend of the same sex that destroys them. If they could just do that, they would save themselves so much heartbreak. Their fear of intimacy is always keeping them at arm’s length.

JM: I wanted to ask you about “St. Dismas” being published in The Atlantic. How was that experience? I felt like before you mentioned that was a big dream of yours.

JL: I mean, who doesn’t dream of having a story in The Atlantic or The New Yorker or the Paris Review? Still waiting on the other two to come-a-knocking. Keep your fingers crossed for me. But, my experience with The Atlantic was great. I had two or three editors who helped me shape it to fit the needs of the magazine and a whole copy edits team that helped make sure everything made sense and had been fact-checked. When I thought of The Atlantic, I always imagined these big, scary editors with no sense of humor, but I’m happy to say that I had the complete opposite—sweet, kind, and very welcoming individuals.

JM: I think that’s a good place for me to ask if you think that Guatemalan Rhapsody is a political book. We’re living in one of America’s most tumultuous decades. We’re about to enter into yet another Trump presidency. Immigration tensions are at an all-time high. It’s very uncertain, and especially for Latinx immigrants the situation is extremely concerning. Were you thinking about the book’s political implications and how you could make an impact?

JL: For sure. No matter what space I’m in it’s always going to be political just because of who I am and how people see me. No matter what, my presence is tinged with something related to difference. Skin color, language, cultural difference. But I am very interested in the history of Guatemala, and it just so happens that its ties with the U.S. have been filled with bloody encounters. I think that anytime someone writes about the country, they will have to address the United Fruit Company and the U.S.-backed genocide known as the Guatemalan Civil War. The thing with my collection, however, is that it doesn’t focus on those years but rather on the aftermath of the carnage that took place. So, while none of the stories in the collection are set on a battlefield or in campsites with the guerilla fighters, all of the characters and their surroundings in the stories are products of that history and the scars, economic collapses, and maras left behind by the exploitations of their ancestors It’s why my parents fled, so it’s also a part of my history. In other words, there is no way for me to disentangle that past from who I am and what I stand for and how outspoken I am about my views and beliefs on social media and in person, so I would say that the book is political in that way—the fact that my existence is always political, so anything I touch or write is tinged with my politics. And I don’t think that’s a bad thing; it’s almost like resistance by mere existence.

JM: Let’s talk about craft just a little bit. How do you structure writing sessions? I know that you have currently isolated yourself in an Airbnb in an undisclosed location. But it’s not always like that. You’re married. You have two young kids. How do you find time?

JL: Yeah, it’s hard. I have to say Taylor, my wife, really holds it down. Without her support, I wouldn’t be able to work the way I do. It wouldn’t happen and so I’m really thankful for that. During the last year I spent writing the collection, I was working as an adjunct, which paid nothing. Taylor was working part-time at a bank and then I took up a second job working at the library, so I literally worked seven days a week. And then, on top of that, I would go spend eight hours a day on Saturday and Sunday and just write because it was the only time I had. In other words, every second of my day was accounted for. Still, it’s something that I really wanted to do, so I found time. That’s the best way I can put it, honestly. Like we’re all busy, we’re all trying to make ends meet teaching classes or shelving books or whatever it is, but I think you just make time for it, you find time for it if it’s what really speaks to you. Writing is so hard. Like writing is really difficult, and we’re all making do with what we can, so if that’s two minutes typing in a notes app while you brush your teeth or, like me now, the ten minutes I get between Bluey episodes they want me to watch, you learn to use that time wisely, even if you’re exhausted.

JM: Earlier you said that you keep working a sentence until you like it, and it sounds good. Were there any stories in this collection overall that you struggled to revise and why?

JL: Again, writing is difficult, but revising is even more difficult. This is why I do most of my revisions as I go. The best way I can explain it is, since I write and re-write that first sentence and that second sentence and then those two together and do the same thing for the third and fourth sentences, and so on, so that by the time I’ve finished my “first” draft, it’s actually draft forty-two or eighty-nine. I let the language dictate the next moment of the story, so I never sit down to plan or plot or outline. Rather, I revise on the go. Maybe one character asks another, “Do you want to fight?” and depending on the rhythm of the language, the other character will respond with “Yes” or “No,” leading the story to its next moment. If I feel as though I’ve got the rhythm wrong the first time, and I change the character’s answer based on what sounds best, then I revise it right there and then and let the story go off to where the next sentence will take it. If it gets to my editor and there are comments on more than half the story, I’m like, forget it. Just throw it away. I’m going to write something completely different. I’ve been doing the same thing with the novel. If all of a sudden, these last twenty-five or thirty pages I’ve written actually aren’t good, and I can tell it’s going to be a lot of revision, I just delete it and start over. If there are a lot of editorial suggestions on a story or chapter from my editor, especially as it relates to structure, then I missed something, and if I missed something, I don’t want to have to go in to figure out where or what it was, I’d rather just start over because it’s obvious I missed something really important, and I think I’d be doing the story a disservice by going in and messing with it with my rational brain; I’d rather erase it all and start the process of discovery from the beginning. I think Eudora Welty did something similar—burning her first drafts before sitting to rewrite it, saying that if it was important, it would make it to the second draft on its own.

JM: Were there any other writers or works that influenced this collection, but also who are your favorite authors in general if they don’t line up and why do they inspire you?

JL: My favorite novels right now are There There by Tommy Orange, Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi. The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri but I also like “Everyone Who is Gone is Here” by Jonathan Blitzer and “All My Heroes Are Broke” by Ariel Francisco. Just from these titles, you can see that most of my influences are contemporaries, but I will read anybody or anything as long as it sounds like music on the page. I know I keep saying that, but it’s true. What makes or breaks a book for me is the rhythm of the prose. This is why I admire poets who write novels or non-fiction so much—you can tell they’re engaging with the language in addition to the story itself.

JM: What did writing this collection teach you about yourself as a writer?

JL: I learned that in order to write, at least for me, I have to be physically uncomfortable. It’s like it has to be too cold or too hot or the space has to be too cramped or the desk needs to be too high up or too low or I need to bang my knee against something every couple minutes. I chug coffee because I’m an anxious person and it gives me anxiety. This is not good advice for anybody. But to me, it feels like an offering to the muses or the Maya gods or the universe or whatever the fuck it is. If I am comfortably sitting in a 70-degree room, if my back doesn’t hurt, if the desk is the perfect size, I’m just going to hang out for a bit. It doesn’t connect me the same way as being in a little bit of pain and discomfort does. To be in pain feels like I’m trading something for something else. It’s some kind of exchange between me and the universe or my ancestral gods, whatever it might be. It feels like I’m sacrificing to them so that they’re willing to part with some things—wisdom, lyrics, blessings—for me.

JM: As you’ve mentioned already, you’re working on a novel, which is huge. How’s it going?

JL: I have a deadline of June 30th, so I feel that stress and hear the ever-present second-hand on the ticking clock. I would say that I’m about two-thirds of the way there, but I still have a lot left to do. My favorite novels are about 250 pages long. I think it’s really a sweet spot, but this is starting to feel like it’s going to be a little longer maybe, like 300-350 pages. I wish I had a more concrete answer other than “it’s going,” but that’s the truth: it’s going, it’s going, and soon, it’ll be done.

JM: Good, I’m excited for you. I was so thrilled to hear the news and huge congratulations to you. Last question. If you could give one piece of advice to a writer working on their debut, what would it be?

JL: Every time I am asked, the advice is always the same: read poetry. Before I sit to write I read five to ten poems, sometimes from the same collection, sometimes from different collections, just to engage with language on a word by word, sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph level which, as I’ve mentioned multiple times is what matters most to me when I’m writing and when I’m reading, and so that’s my advice.

+++

Jared Lemus is a writer of short fiction whose stories have appeared or are forthcoming in The Atlantic, Story, The Kenyon Review, among others. A Latine writer, Lemus has been a Tin House Scholar and Colgate Writers’ Conference fellow. He holds an MFA from the University of Pittsburgh and is the Kenan Visiting Writer at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill.

+

Jess Maxwell is a teacher, writer, and photographer living in Little Rock, Arkansas. Her work has appeared in various venues, including poets.org, which published her poem “Gemini,” winner of the Academy of American Poets Joy Taylor Rieves Prize. She previously served as the Associate of Editor of Jabberwock Review and is currently Co-Director of the Zeitgeist Reading Series.