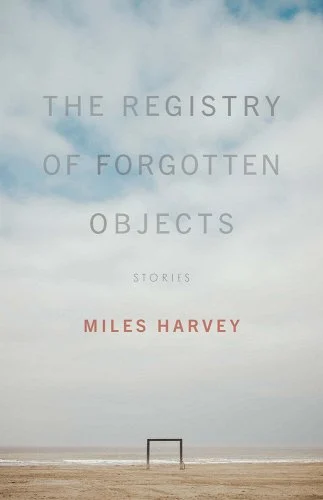

Miles Harvey’s debut collection The Registry of Forgotten Objects (Mad Creek Books, 2024)looks at the stories of the objects in our lives, how they change meanings, and tie the past to the present in new ways as they drift between and among people’s lives. Each of these stories explore how objects evoke strange and interesting facets of the human experience, from how one barbershop pole goes from illuminating a store front to being boarded up underneath the bed of a crumbling marriage, or how one person’s lullaby becomes the catalyst behind another’s downfall.

Charles Baxter writes:

This astonishingly beautiful book of interlocking stories has at its center things and people that are about the disappear…. It is as if all these stories compose one large story, an emotional journey of the lost and found…. A wonderful book.

Joseph Thomas spoke with Miles Harvey about the stigma against pictures in literature, the advancement of AI technology in creative fields, and the role of research in the process of writing historically influenced work.

+

Joseph Thomas: Congratulations on this new book, I’ve thoroughly enjoyed having the chance to read it myself, and I’m sure this is the case for many others as well. In a way, The Registry of Forgotten Objects is a narrative of things, and in many places throughout the book I found myself putting more importance on the journey of objects as they change ownership than I was on the people who owned them. In this way, are there any objects in your life that you think will transcend their importance to just you? Are there any that you think already have?

Miles Harvey: Objects generally outlive human beings, often by centuries, and they take on new meaning for each new person who comes in contact with them. So yes, I suspect that many objects in my immediate surroundings will have significance to somebody long after I’m gone. On the desk at which I’m writing these words, for example, is a lovely if somewhat worm-eaten book, published in 1838, which I picked up for a dollar or two at a rummage sale some years back. Who knows how many people have owned, borrowed, thumbed through and otherwise pondered this particular copy of Dr. Butler’s Atlas of Ancient Geography? Who knows how many daydreams its hand-colored maps have inspired? Near the front of the book, scrawled in faded ink from a quill or steel pen, are the words R.H. Hobart / Sophomore Class / Dickinson College / Carlisle, Pa. This long-dead undergrad appears to have been a certain Robert H. Hobart, who, some quick research shows, was enrolled at Dickinson in 1839 and later seems to have fought in the Civil War. On the frontispiece of the book, there’s another name, written indecipherably in pencil and accompanied by a series of mathematical operations, as if some distracted soul had used the book to balance his checking account. A more recent owner, meanwhile, rubber-stamped the words Library of Harvey M. Bricker into the atlas in bright red ink. I later discovered that Bricker was a retired anthropologist from Tulane University. Fearing the book might be stolen, I contacted him. He seemed surprised that I had it but assured me that Dr. Butler’s Atlas no longer was his. (My theory is that gave the book as a gift to someone who had no interest in a bunch of old maps.) Just now, I looked Bricker up on the internet and discovered that he’s been dead since 2017. That book obviously outlived him, just like it outlived R. H. Hobart and all the other people who have cradled it in their hands, as I was doing a minute ago. It’s sure to outlive me, as well. Although it’s in poor condition and not particularly valuable, I hope to donate it to a library.

Not every object comes complete with the former owners’ names, of course, but hundreds of commonplace items in my house have histories of that predate my time with them and will continue long after I’ve passed on—an antique dining-room table one of my wife’s friends gave to us because she got a new one, some random old tools I picked up at various garage sales, a brick I stole from the demolition site of Comiskey Park, where my grandfather, who died long before I was born, used to take my mother, now dead as well, to watch the great knuckleballer Ted Lyons pitch for the Chicago White Sox in the 1930s. There’s story in the collection called “Balm of Life,” in which a woman suddenly starts noticing all the knickknacks that have accumulated in her home over the course of decades. “Where did all these things come from?” she asks herself. “Where would they go after she was gone? Would they wind up in someone else’s house, then someone else’s, people only vaguely conscious of their presence, people who couldn’t explain their significance any better than she could? Strange to think they had lives of their own.” In The Registry of Forgotten Objects, I wanted to pay close attention to those lives.

JT: You have an extensive background in non-fiction writing, and you make frequent references to history throughout these stories, especially regarding Sappho and antiquity. With this in mind, I want to know what your writing process look like when you’re just starting a story. With “Song of Remembrance,” for example, did you start with Sappho and get inspired to write an Ahabian quest for the lost melody, or did you have the idea of the scholar as a character first?

MH: Due to my intuitive and scattershot approach to the writing process, it’s a little hard for me to offer too precise an answer. But one thing’s for sure—that tale did not start with Sappho, whom I knew almost nothing about when I began working on the piece. My intention was to write about a song—one that has survived for countless generations without anyone much noticing, the way some objects do. The protagonist of my tale—a scholar who in the 1930s becomes obsessed with the idea of an ancient song that “had been on people’s tongues … long before writing, long before the reach of recorded history”—was inspired in part by a now-legendary classicist named Milman Parry, whose exploits are documented in Adam Nicolson’s masterful Why Homer Matters. Between 1933 and 1935, Parry travelled to remote mountain villages in Yugoslavia to make recordings of illiterate musicians as they sang long epic songs from memory. His audacious goal—one that clearly captured my imagination—was to draw a 4,000-year through-line between those songs and Homer’s poems, The Illiad and The Odyssey.

I can’t recall how I got interested in Sappho, other than the fact that she sang her poems. But at some early point in my research, I came upon a few lines of her verse: someone will / remember us I proclaim / in another time. Those lines, which wound up playing an important role in “Song of Remembrance,” are all that remain of a longer Sappho poem that has been lost to time. In fact, of all her work, only one poem has survived complete. The rest are fragments—often only a few suggestive words. And as time went on, I became obsessed with these fragments, which are beautiful in their own right but which also draw attention to what’s not there, what might have been, what can never be expressed or known. The Registry of Forgotten Objects is full of such dark holes, including the disappearance of a young man who vanishes without a trace early in the book and whose void alters the physics of several other stories, such as “Song of Remembrance.”

JT: Your stories “Postcard from a Funeral” and “The Complete Miracles of St. Anthony” contain images that supplement the narrative, offering a visual representation with arguably more clarity than the words alone could have portrayed. There seems to be a stigma in literary fiction against the use of pictures to show objects in this manner, and so I want to ask what your thoughts are on this? Are you generally just in favor of images in fiction, or do you maybe think it should vary on a case-by-case basis?

MH: If such a stigma exists, I think it’s sad, not to mention ridiculous. I’ve used images in all my books—not just as a means of illustrating the text but also as an attempt to create meaning beyond the reach of words alone. One of my favorite writers is W.G. Sebald, whose stunningly original novels are full of black-and-white pictures, many of them blurred snapshots that Sebald supposedly found in junk shops or old photo albums. He once said he used these dreamlike images to transport readers “from the real world into an unreal world; that is, a world of which one doesn’t exactly know how it is constituted but of which one senses that it is there.” But my own theory is that he also realized the limits of language—that he understood, for example, words can never fully express the horrors of war or the Holocaust. Some writers, such as Kurt Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse-Five, have used irony to deal with this difficulty of speaking the unspeakable; Sebald chose to get at the problem through images, employing them to draw attention to the failure of language, as well as to create a new kind of semiotics.

I’m certainly not claiming to be the second coming of Sebald, but I’d argue that the images are essential to both the pieces you mentioned. “In Postcard from a Funeral,” the story is structured around an old postcard, and the text on the back of that item plays a key role in the narrative. In “The Miracles of St. Anthony,” which tells the story of a con artist posing as a priest, each section of the narrative begins with an excerpt from the book he claims to be writing, based on his supposed discovery of “lost accounts of St. Anthony’s miracles.” The pictures are from this completely non-existent book—putting readers in the same position as the con man’s victims and perhaps also transporting them “from the real world into an unreal world,” to quote Sebald.

Look, Library Journal recently reported that graphic novels are now the third best-selling genre in the U.S. and Canada, behind only general fiction and romance—evidence, perhaps, that the written word is losing its currency in the digital age. So I get why there’s some pushback among my fellow practitioners of literary fiction. But if the use of images is just some superficial gimmick that brings nothing to a narrative, why do so many authors allow images to sully their book jackets? Shouldn’t the title alone, presented in a modest and uniform font, suffice?

JT: You of course have been writing fiction for years, with a long list of published short stories and your MFA at Ann Arbor, and so I want to know which authors in particular inspire your writing or have an influence on your work?

MH: I’m not much of a list-maker, and I love many different styles of literary fiction. But if you walk into my office at DePaul University, the first things you’ll see are two big posters—one of Virginia Woolf and the other of José Saramago. Some other fiction writers who have played a big role in my imaginative life are, in no particular order, Jorge Luis Borges, Italo Calvino, Alice Munro, Toni Morrison, Charles Baxter, Jenny Erpenbeck, Haruki Murakami, László Krasznahorkai and Sebald. But I’m always accumulating new favorites. In the past year or two, I’ve been blown away by Lars Gustafsson’s Stories of Happy People, Tom Drury’s The End of Vandalism and Gert Hofmann’s The Film Explainer, to name just a few. And I’m currently reading Alba de Céspedes’s The Forbidden Notebook, which—so far, at least—is sublime.

JT: In “The Drought,” you present a city with a strong personality formed around the circumstances of the weather, but you seem to leave the city itself unnamed. Was there a certain rabbit-hole of research you particularly enjoyed that led you to the idea for this story, and therefore wanted the place unnamed to sever historical ties, or is the idea of the unnamed place serving a more important role in the collection as a whole?

MH: The setting is not the only thing I left unnamed in that story. The main characters are identified only by as “the weatherman,” “the station manager,” “the barber” and “the barber’s wife.” I did this, I suppose, because I wanted to give the story a mythic feel. If you read the Brothers Grimm—and I highly recommend the recent translation by Jack Zipes—the stories invariably begin with sentences like this: In olden times there lived a king … A poor woodcutter lived at the edge of a large forest … Once upon a time there was a fisherman …

I wanted “The Drought” to have a similar sort of heightened reality—but in order to pull it off, I had to make the details even more concrete than I might have done with a more naturalistic piece. The setting might not be named, but I put a lot of time and thought into creating a very specific story-world. I’m reminded of what Gabriel García Márquez once said about “a journalistic trick” he used to make the fantastic seem real: “If you say that there are elephants flying in the sky, people are not going to believe you. But if you say that there are four hundred and twenty-five elephants flying in the sky, people will probably believe you.” He went on to note that One Hundred Years of Solitude “is full of that sort of thing.”

JT: In many of these stories, but especially in “The Master of Patina,” you explore ideas of imitation and what qualities make something genuine. This is an especially interesting question right now considering the evolution of AI services like ChatGPT, and I’m sure that as a professor you have an experience with AI generated text, voluntary or not. So, I ask, aside from teaching where there are obvious reasons why AI writing is bad, do you have a strong stance on this topic? If AI, for example, evolves to the point where it is indistinguishable from human-generated writing, and you derive the same kind of enjoyment from reading it, would it matter to you if it was written by a person or not?

MH: That’s a wonderful question. I wrote that story before the invention of ChatGPT and the infiltration of AI into virtually aspect of our lives, including literature. But you’re right: “The Master of Patina” asks whether a fake work of art can really be thought of as fake if we’re swept away by it emotionally, intellectually and aesthetically, just as we would be with original work of art. And to be honest, I don’t really have a firm answer to my own question—or to yours.

I’ve long argued AI would one day prove to be competent, and perhaps even good, at crafting the kind of narratives that already depend on heavily on formula—superhero movies, for instance. And based on a recent story in The Atlantic with the ominous headline, “There’s No Longer Any Doubt That Hollywood Writing Is Powering AI,” it sounds as though that day is already here.

Maybe it’s just wishful thinking, but I’m not sure AI will ever connect with people the way that real works of literature do, and by “real” I mean idiosyncratic, unpredictable, lyrical, strange, wild, beautiful, disturbing—in other words, fundamentally human. For me, the relationship between reader and writer is about as intimate as two people can get outside of (and sometimes including) sex—an idea I explore in the story “The Man Who Slept with Eudora Welty.”

JT: It’s been a few months now since The Registry came out. What have you been working on since then; is there another big project you’ve started on already?

MH: I haven’t quite landed on a new project yet, though I’m playing with several ideas. One of the challenges is that I recently became chair of the English department at DePaul University—a real test case for the Peter Principle. I’ve always been a painfully slow writer, and it turns out that I’m a plodding administrator, as well, so time is an issue. But by this point in my career, I’ve learned to be patient with my snail-paced production. Another book will find me soon enough.

+++

Miles Harvey is the author of The King of Confidence (a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice selection), Painter in a Savage Land, and The Island of Lost Maps. He teaches creative writing at DePaul University in Chicago, where he chairs the Department of English and is a founding editor of Big Shoulders Books, a nonprofit, social-justice publisher. The Registry of Forgotten Objects is his first work of fiction.

+

Joseph Thomas studies creative writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. His work has appeared in the The Laurel Review, and Nebo: A Literary Journal, among others. He is an editorial intern for the independent literary press Braddock Avenue Books and the managing editor of Equinox.