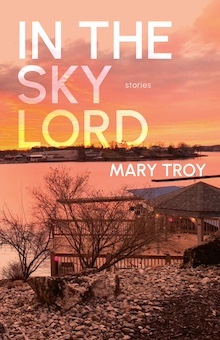

Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, Mary Troy recently released her sixth book, In the Sky Lord, a collection of ten stories that slice open the beating heart of the Midwest to reveal a world in which characters work to understand the paradox of modern community. In language that sings with both compassion and an often tongue-in-cheek rough humor, Troy’s truly original characters all ask, in one way or another: What is a life lived well?

Mary Troy’s previous work has won the USA Book award for literary fiction, the Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award, a Nelson Algren award, a William Rockhill Nelson award, among others. Alice Kinder had an opportunity to talk with Troy earlier this fall.

+

Alice Kinder: Most, if not all, of the stories in In the Sky Lord are intertwined with the others in some way, which means that you must have loved a character enough to decide that their story just couldn’t be over yet. Can you talk a little bit about what it’s like to fall in love with characters as they tell you their story?

Mary Troy: What an interesting way to put it! And you are right that the characters’ stories are not over just because the story ends. I like to think most of my characters continue on. Some characters become too fascinating to ignore, though, and the more I know about them, the more fascinating they become. I learn about them by questioning their actions and trying to investigate that crack between what they do or say, what they want to do or say, what they know they should do or say, and what they will later say they did or said. The more I write, the more I question, the more complicated they become, and complicated means fascinating or, as you say, love. Some of them I like less, but cannot stop investigating. A good example of this is Millie Kick in “Rent to Kill.” She was Millie Holmes in a story I wrote nearly twenty-five years ago, “Do You Believe In The Chicken Hanger?” That story was one of the Nelson Algren award winners, a runner-up, and in it, Millie Holmes’ cheating husband has left her, and while needy and cold and slightly drunk, she agrees to go to a motel with a friend of her husband’s, and they choose a sort of famous no-tell motel on its last night of operation. News people are there; it leads to Millie’s humiliation and a public forgiveness ceremony at the Catholic grade school where she teaches, and finally to her quitting teaching, something she loves. I grew attached to Millie and worried about her for years, wondered what happened to her. Then I found her in “Rent to Kill,” gave her a new way to make a living, and had her fall for a dying man. So she was a character I resurrected from a previous story and collection. She is also in the last story, “A Goat’s View,” now living with her new mother-in-law, mourning Max, the man she married without knowing too well, but just falling in love with when he died. Even now, I am not convinced Millie’s story is finished. And Jewel who first appears in “River Dogs” as a minor character is again a minor character in “700 Million Billion,” and I may write a story just for her someday. As with Jenny who is the widow in “Reecie’s Last Race” but has her own story in “Mission of Mercy.” Her life, married to an older man, and that marriage giving her two stepsons merely four and five years younger than she, intrigues me. I go back to your original question: what is it like. The answer is it’s like magic to fall so in love with my characters that I want to use them again, to continue their stories. I already know much about them, but I trust they can still surprise me.

AK: In your opening story, “Rent To Kill,” we read of two people who are trying to remain resilient despite how alone they feel. After their first meeting, they get to know each other as many people do, through often mundane fun facts and memories, a method that ultimately maintains a certain distance between them. Can you tell us a little bit about what you feel these small markers of intimacy mean for Max and Millie, especially as they know their time together is short?

MT: How nice that you ask about the same story, “Rent to Kill,” I just talked about. I like the mundane facts Max and Millie share, for that shallow talk, supposedly meaningless, is how many of us communicate, is what we share when we are new to each other and hoping for a connection. All those minor details are suddenly quite fascinating to the teller, for she has a new audience, and to the listener who learns new facts about a new person. So even if the facts are mundane, they are not yet boring. And I do not believe any of them are meaningless. All are part of what makes us us. And Millie thinks the talk is like honey poured from above, connecting them all. I believe talk does connect, and can be the beginning of love, but that line about honey also says something about Millie’s loneliness. Millie and Max eventually reveal more than surface details, though. Millie talks about her need to be special at something, to be as good as the egg boy, and Max talks about his drama queen and self-centered mother as well as his love of teaching, the lengths he goes to be sure the students get something from his classes. And Max helps Millie in her work, too. Eventually, as they become more connected, even Millie’s dog, Delilah, becomes attached to Max. Finally he reveals the deep truth he has been hiding, that he is dying. In this story, I wanted the intimacy to grow incrementally, to start with the mundane and silly and jokey, and move into revelations of deep yearnings and hurts, so Millie can finally say as she holds Max in the back of her van that feeling is all, that she feels his essence. And it is Millie who helps Max die in the way he wished. But she knows she may not know him as well as she could, that people may not be who they are when they are dying, and she wishes she had known him in that thick meaty part of life, so far from his own death it seemed he would last forever. And in the last story in the book, “A Goat’s View,” she says one thing she knows for sure: Max was good at dying.

AK: Food is often one of the most revealing symbols in literature, and several stories in your collection use food as a symbol of kindness and connection: soup in “Mission of Mercy” and Dad’s butter cakes in “Butter Cakes.” This second story actually has many scenes where the characters are eating or at least discussing food, and so I was just wondering, did you find that in writing this story your characters exposed themselves through their food choices?

MT: Food is the most basic thing we share with one another or offer one another. We meet with friends for lunches or dinners or coffees or drinks; when friends come by, we offer food and drink; the cooks among us make elaborate delicious meals for those we love, but never for only ourselves; and we call foods heavy in fats and sugars comfort foods, resort to them in times of stress or sadness. So food is solace, food is kindness, food is what we can give when nothing else will work. Two stories in In The Sky Lord use funeral parties for the present action, and the food and drink, either at Karla’s home or at the Pig Trough restaurant, are offered because nothing else will work. In “Butter Cakes” the butter cakes are made from a recipe from Ralph’s dead wife, and are so good he can believe someone would give him an award for being kind. They are what he includes in every last meal for the Missouri condemned. And as further kindness, he makes whatever the soon-to-die want, no matter how elaborate, even bouillabaisse. Ralph wants to give as good as he can, even though he himself prefers extra hot canned chili washed down with a vodka tonic. In “Mission of Mercy,” Brandon’s gift of cans of soup is a way to make up for falling for a scam, for ordering so much soup. Each can that comes free with the rooms is in fact a gift to his mother, a way to make amends and to make her less sad. So, in answer to your question, yes, characters do expose themselves by their food choices, through what they offer to others as well as what they choose. Take Barbara in “The Golden Flapjack,” a woman who is grieving the death of her son, a woman who gets free food as she harasses Imogene. Barbara chooses chicken gumbo and strawberry pie, one heavy in salt and the other in sugars, her versions of comfort food. And the food is given by Chloe, the Golden Flapjack manager, to appease, to comfort. It is what little can be done for a woman mourning her dead son.

AK: Many of your stories mention a specific city or town in the Midwest, these places of course meaning much more than just a physical place where the story is happening. Can you talk a little bit about what the feeling of the Midwest invokes for you, and how you think it’s used in your work?

MT: The Midwest is a large place, but my section of it is one of amazing beauty, a beauty that, like many beautiful places, is easy to take for granted, to stop seeing. I write about the Midwest, my Midwest, because I do see the geography, am aware of its changes and of the flora and fauna native to my section, and also I am interested and occasionally impressed by what we have altered to make our mark on all this. I mean I find charm in cities and towns. One could say the bluffs and rocks and water, the geography around my area of the Midwest—the confluence of mighty rivers (the Mississippi, the Missouri, and the Illinois) as well as the rocks and clear springs and lakes and rivers of the Ozark plateau—represent both stubbornness and resilience, the rocks hard to change and the rivers constantly changing. But I think that would be forced and reaching too far. Because I find beauty around here, I use it as a setting for complicated lives. Beauty is never simple and calls for more complication. I can say, too, that Midwesterners are what we all are: polite and rude, ignorant and wise, educated and uneducated, open and friendly and closed and suspicious, fast and slow, sophisticated and countrified, funny and sour, and any adjectives you could think of. None of us are what we seem or what we want to be. The Midwest is large, as I said, but my area of it has a history different from Wisconsin, Michigan, Kansas, or Minnesota. We were once a people who used and depended upon rivers for commerce and transportation, who tricked and mistreated indigenous people and took their lands, and who, during the Civil war, Missourians and some in Southern Illinois, too, truly lived that brother against brother cliché. Does any of that inform my characters? I think it must as it informs me, but the lines are neither straight nor direct.

AK: You have published several short story collections and two novels. How does your process in writing the two genres differ?

MT: Short stories may be harder, but I love them more. All writing is hard, and all literary fiction—the genre my realism falls into—requires characters who are as complex and intriguing as we are, so none of it is easy. Fun, yes. Easy, no. Novels may take more time in the beginning as a character’s world must be known enough for plots and subplots to emerge. But once a large chunk of the novel exists in my head and on the page after page of notes I’ve written, then it moves fairly fast. Fast is a relative term, and for me it means I can have a first draft in about a year. That first draft will usually show me all the wrong turns and what is often the biggest fault, a very bad ending. But it will also show me where the ending could be, what it could be, what I have not seen or have written around. Then it takes more years, three or four more drafts. A short story can begin with playing about with a character, with having a character talking—much like a novel—and then I search not so much for plot as for action/circumstance/incident that will cause that character to act or react. This is harder and is like writing in the dark, being blind much of the time. A book of short stories can take a decade, but many if not all the stories have been published along the way. And for each story I aim for that wonderful thing—a story that cannot be summarized, a story that needs itself for meaning, for effect. Of course, aiming and hitting the bullseye are not the same.

Writing novels and writing short stories are more similar than different. Both require exploration, questioning, development, avoidance of the expected or simple. Also, both can take various forms and perspectives so that another hard part is in choosing the method of telling.

AK: What’s next for Mary Troy?

MT: I am writing a novel now that takes place in Wolf Pass, Illinois, a place of prominence in In The Sky Lord, a place I’ve created by taking a real place and modifying it slightly, a tiny town at the confluence of the rivers just forty or so miles north of St. Louis. It is a beautiful place, so the characters will be complicated. A few characters from In The Sky Lord will appear in the novel. I am also trying something different, different for me. I want to write chapters that can stand alone, that can be published as stories before they are put together in one novel. Not exactly a serial, for no cliff-hangers, and not a novel-in-stories either.

+++

Mary Troy is the author of five previous books—three collections of short stories and two novels: Swimming on Hwy N, Beauties, Cookie Lily, The Alibi Cafe and Other Stories, and Joe Baker Is Dead. She has won the USA Book award for literary fiction, the Devil’s Kitchen Reading Award, a Nelson Algren award, a William Rockhill Nelson award, and more. She is Professor Emeritus at the University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Alice Kinder studies Creative Writing at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.