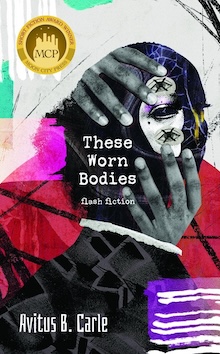

These Worn Bodies (Moon City Press, Nov. 1, 2024) by Avitus B. Carle is collection of flash fiction that is wondrous in its form and its imagination. Bodies are deconstructed to discrete parts (boobs! orgasms!) or made of paper or popcorn. Flies are elevated to main characters. Agency is for everyone. Both societal and genre expectations are defied, exploded. There’s a playfulness infused into themes that are terrifying—poverty, addiction, enslavement, sexual abuse, child abandonment, murder of trans people—to make a collection that is simultaneously whimsical, serious, and deeply unsettling.

I was honored to speak with Avitus about the playful deconstruction of human and narrative form, the upending of regressive gender expectations, the POV of small animals, and how tiny stories can both create and destroy.

AW: I read, “Bite,” the first story of this collection, and thought “Shots fired!” These girls have bullets in their mouths—tasting and coughing them, biting them back, and they’re also words and laughter. It encapsulates so much of what These Worn Bodies is doing. By the time we reach “Call Me Verdean,” which is near the end, I’m so ready for—and yet also blown away by—the sentence: “I can still taste the metallic tang of the bullet, my tongue tracing the holes it left behind.” It’s a different bullet that means something completely different, yet there it is in someone’s mouth. Can you tell me about the journey you’ve created through these stories?

AC: “Bite,” a micro with young girls following in the footsteps of their mothers and grandmothers, felt like the right opening. I also knew “Define a Good Woman” would close the collection, delivering the message that a good woman can’t be defined because the experiences, bodies, and choices are all so different.

AW: So we’re moving from meeting expectations to defying them? As much as you’re building something in this book, you’re continually tearing things down. That feels like the crux of your collection–this idea of being undefinable and ever in motion.

AC: Yes, especially with the title, These Worn Bodies, insinuating that the characters are tired of being put in this one role. They’re seeking to not only define themselves in a more freeing space, but also to break free from definitions imposed upon them.

AW: The stories do that physically as well, breaking out of traditional structures.

AC: The whole collection is an exploration of breaking the rules. In some ways the structure reflects on what writing is. We can have the paragraph form that we’re used to, but also we can experiment and explore how writing changes when we apply different structures to it, in the same way that characters change in search of not only a new identity but also a new way of looking at life.

“Vagabond Mannequin” (a story in the form of a crossword puzzle) is an example that highlights how structure changes in writing as well as the character changing. There’s also “My Dead Sister Looks Good On Me,” as a dark example of character transformation. The only way she feels like she can fit is to take on the role of her sister.

AW: That story is wonderfully creepy. It made me rethink what “worn bodies” means in the title. Maybe we can wear bodies—even other people’s bodies—like we wear clothes.

AC: It does work with “My Dead Sister Looks Good on Me.” It also works for “My Brother Scarecrow”—the clothes in the chest that embody the mother and grandmother.

AW: But it’s not what the title means, is it?

AC: The title was inspired by the feeling of exhaustion at the roles we’re expected to play even if we don’t fit the example. Women are expected to be natural caregivers while men are expected to be breadwinners, a perception that is different from how I was raised (both of my parents worked full time). The title is also a play on how the characters are tired of the assumptions and duties imposed upon them and seek (not always healthy) ways to escape these roles or reveal who they really are.

I like to explore gender roles, especially from a woman’s perspective, because as a Black woman, I tend to break them quite often. I’m not the one you’ll find in the kitchen. I’m not one who wants to have a whole horde of people at my table and I’m like the head of the household trying to make everyone feel comfortable. I’m not the nurturing woman in the family. It’s just not me. I’m more off by myself and I’ll join company, but I don’t want to be in charge of making sure everyone’s ok.

But in my stories, I like to play with characters who embody all different roles.

AW: Even human bodies break out of traditional structures. We have scarecrows, people made of paper and bone, or soda. They’re also split apart—breasts as separate characters, orgasms as separate characters. In “Black Bottom Swamp Bottle Woman,” we get “His eyes in coke bottles. His lungs in water bottles. His heart beating in a bottle of pennies and his lips still talking in a model ship bottle, his secrets raising the sails.”

AC: The body is forever changing. To become someone else, to lose an eye, even to imagine the body as living, dead, a soda bottle, fly, or a guinea pig suggests that some sort of change has occurred. My stories tend to lean towards exploration of the bodies my characters inhabit and how they interact with the world.

AW: That fly story is one of my favorites. Animals, especially small ones, are main characters in many of your stories—mice, rats, rabbits, a bug-size human, a gerbil named Gertrude Stein. These stories explore agency and power, examining what it is to live on the fringes of someone else’s world and still be fully real. Why do you center these seemingly insignificant creatures?

AC: We’ve all felt “less than” or “insignificant.” I love telling stories through the perspectives of animals, because each story is given new life with more at stake. In “12 Moments in the Life of a Fly,” a fly’s life expectancy is between 15 to 30 days. To humans, that’s a short amount of time, but to them it’s an entire lifetime. In the rabbit’s case, to eat her children is a means of survival, knowing the kind of life that awaits them and herself.

The choices and conflicts my animal characters face are quite human. However, the solutions may vary because we’re bridging the gap between human and animalistic instincts.

AW: That reminds me of the zombie story, actually.

AC: In “Call Me Verdeen,” the character has been turned into a zombie, and now she’s trying to navigate this new life: “I’m a zombie and people don’t like me anymore. I want to join other humans except I also want to eat humans.” There’s a complex balance between the surreal and reality and also human tendencies in seeking company vs. this need for distance.

AW: It’s human to be hungry.

AC: It’s perfectly zombie to want to eat a brain.

AW: Eating weird things comes up a lot. In “Plague,” “A girl fills her father’s mouth with dirt. So the worms will accept him, she says to the Body Collector.” In “Soba,” a ghost “laces a bit of herself within every noodle” and “girls drink her tears.” And it goes both ways: “Through pursed lips, she devours their souls the same way they slurped the noodles she slices.”

AC: The mouth is definitely an opening, a new way for the body to receive and, if you will, digest information. Much like the eyes are a way to visually devour information, and ears to receptively digest information. I’m more drawn to the mouth as a way of exploring human interaction and tenderness because to feed or kiss or lick or bite suggests a closeness and tension that’s really fun to explore.

You can have characters express themselves through dialogue, but I like to get to that on a deeper level, through what they’re eating or not eating. They eat in front of people or they eat by themselves. I enjoy this other layer of a character getting to know themself and seeing who accepts them through what they eat.

AW. There’s something about taste, how intimate it is. In “the Patron Saint of Keys,” a character who can’t speak “licks the shape of their names.”

AC: You can shout at someone from across the room and still not be close to them. It builds a barrier vs. when you‘re whispering in their ear. But you can also lick the outside of their ear and it brings you closer. It might be a romantic lick, or it might be something more vicious.

AW: There’s so much playfulness that one might expect the content to be light. But we get stories that are deeply political and deeply moral. They’re about injustice and oppression, but they’re also funny.

AC: Adding an element of comedy or levity not only depicts how my characters navigate their situations, but also adds another moment for readers to hold on to. I’m interested in the ways comedy helps us cope with or avoid tragedy. Not all my characters will find a happy ending, but they can still have moments of whimsy.

AW: I love this. We need holdable moments or else the story slips away from us.

AC: Comedy, as well as a coping mechanism, is a way to view the world. You have comedians who tell really dark jokes and have the audiences laughing, and then they tell the joke again, and you realize the dark undertones, but it’s also easy to remember because in the moment it was so funny. It clung to you, and you were able to retell it.

The comedian that I often reflect upon is Richard Pryor, who had a very dark childhood and turned his whole experience into comedy. He would get onstage and talk about his family, his grandmother raising him in a brothel, being surrounded by drugs and smoking and alcoholics. And he would turn it into humor, so it would stay with audiences.

I also play with that in my story “Comical.” You have the comedian even though you don’t hear the jokes he’s telling. He cries and keeps saying “I got the laugh, I got the laugh.” It’s a reflection of comedians who put themselves on the stage and audience will laugh, but the comedian still has to live with what they’ve experienced.

AW: If you’re using funny moments to get the reader to pull a deeper message back into their life, what’s the message?

AC: I want readers to remember my characters the way that my characters would want to be remembered. And my characters do have moments of fun, even though they’re going through a hard time, a breakup or they lost their child or they’re losing themselves. It’ s real that we have dark times in our lives, but we have moments of joy as well.

AW: So much of the collection is about breaking apart or exploding expectations. Does that make it harder to come away with a something? Or does it mean the something is more complex?

AC: The something is definitely a little more complex. I don’t think the body or the person can be fully defined because we’re constantly evolving. I wasn’t the same person I am today when I was in high school or when I was in elementary school or kindergarten. I probably won’t be the same person when I’m in my 80s because I’m constantly changing and discovering things about myself.

I wanted this collection to be a reflection of that, where all of the characters are constantly changing. Change isn’t necessarily a bad thing, nor should it be feared, but it should be celebrated. Sometimes characters look forward to it in wariness and sometimes they’re excited and sometimes they’re still discovering who they are.

+++

Avitus B. Carle (she/her) lives and writes outside of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Her stories have been published in a variety of places including X-R-A-Y Literary Magazine, Fractured Lit., JMWW, SoFloPoJo, The Commuter (Electric Literature), and elsewhere. Her debut flash fiction collection, “These Worn Bodies,” was published by Moon City Press. She can be found at avitusbcarle.com or online everywhere @avitusbcarle.

+

Allison Wyss is the author of the short story collection, Splendid Anatomies (Veliz Books, 2022), which was a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award. Her stories, essays, reviews, and interviews have appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Cincinnati Review, Water~Stone Review, Monkeybicycle, Split Lip, Lit Hub, and many other places. Some of her ideas about the craft of fiction can be found in a monthly column she writes for the Loft Literary Center, where she also teaches classes.