It was last April that I found a moose carcass in the woods. When I discovered it, I resolved to keep it a secret. But then, the moment I got home I called a friend and we went out to visit it. Fine, I figured. My friend was exactly the right guy to tell, and he had his own reasons for staying out of further trouble in the woods. Who was he going to tell anyway? He lives in the only house at the end of a mile-long discontinued dirt road.

My Neighbor Jack and the Moose Skull

But, evidently, I can’t keep a secret. I told John Emil Vincent several weeks later when we were at a party. I had decided John was very unlikely to spread the word to the wrong people. Besides, we were at a nice party, and this peaceable gathering of like-minded friends needed to be told a gory story before someone started talking about kale or something even worse.

John is an editor of the literary journal the Massachusetts Review, and in that capacity he immediately offered me a devil’s bargain: I should write this story up and submit it to the journal. I told him that would be a great idea while simultaneously believing entirely that this was a terrible idea. But what the hell. Nobody who could make trouble for me was likely to read a literary journal, and what’s more, I’d probably never even write it.

The Massachusetts Review, Volume LV, Number 1

I didn’t want to get in trouble, because when my friend and I visited the carcass, we took parts of it back home. But more personally, I just didn’t want to put what I do in the woods into words. I ramble around the forest here frequently, and when I’m working as a writer, it is a wonderful thing to not bring language with me. I can be as observant or blithe as I want to be, and as long as I don’t vanish under the ice or get mauled by a bear, it just doesn’t matter to anyone but me, and no homework will be assigned.

So, on an afternoon while I was feeling contrarily tempted by my own inhibitions and the lure of publication, and also when I was on my seventh or so cup of coffee, I met with Oliver Broudy, himself a writer, editor, and the host of Amherst Live, a “live magazine” which he was then first putting together. I was telling him I might not be suited to be his show’s poetry editor. I think I must have been holding forth on my own unsuitability—I had already described how much I loved how bad the new Swans album made me feel, and how the only way I could face my business school students was to blast Amon Amarth before work and pretend I was holding an invisible battle ax when I taught.

I must have already had my mental folder of “What Not To Say at an Interview” open. So I went on to tell him about how I’d cut the head off a dead moose last month. I guess Oliver liked the looks of the grave I’d been digging myself verbally, and he proposed I tell the story on stage. I couldn’t believe it. There I was, actively illustrating my point that I was the wrong man for the job, and somehow I got myself conscripted anyway. It wasn’t till weeks later that I realized I would be telling it “Moth-style” with no notes and that I’d be on camera and in front of over 200 people.

A few months later, and I did just that. I memorized the entire essay, which became a fifteen-minute-long monologue, and performed it in front a big crowd at a very well-produced event, where my chief concern was to not pass out on stage. A friend noted that I kept looking down during the performance and asked if I had notes taped to the floor. Nope. I was picturing a dead moose in front of me in order to calm myself. It was filmed and broadcast on local radio and TV. So much for my secret.

Here’s a video of that performance on Amherst Live:

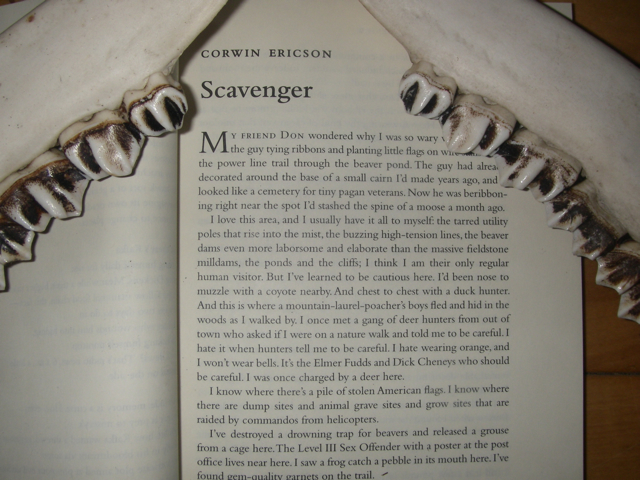

It’s nearly a year later now, and the issue of the Massachusetts Review just arrived in my post office box. John recounts our party conversation in his foreword to the issue and cites my “dogged work at revision.” That work of revision was fascinating. This essay, “Scavenger,” began as a carcass. I can see the moose’s skull right now, here in my house—I scavenged the carcass for a story and its bones. I had two different skilled editors and a drama coach helping me revise the live and the written versions. Each of these people had different agendas and advice that sometimes contradicted the others. I pushed hard against my own best or worst intentions—I still don’t know which. I was quite actually stripping the flesh off the bones while fleshing out the story.

Just yesterday I walked past that bog where this whole story began. It’s under more than a foot of snow and ice now. I told the bog about my plan to write this very essay and how I was resentful of it, since now I had to figure on how I was going to have to bring language back from my walks, and it was the bog’s fault. How the very act of speaking to the bog wasn’t the sort of thing I like to do. As a consolation, I told the bog that maybe it would be fitting that, when my time came, I would lay myself down here, like the moose. And the bog said, “I don’t care.”

The Bog