1. It took me a long time to appreciate Robert Bresson’s films. Not long, as in I had to see his films repeatedly before I was able to appreciate them. Rather, I watched a lot of other films and directors before I ever even came to Bresson. But this is just as well, for I had to go through other films to prepare for him. Plus, I thought Bresson might be overrated, and whenever I suspect that, I respond stubbornly by resisting something. I have resisted a lot of things I later came to love. But timing is everything, and sometimes one has to avoid answers before answers can become answers.

2. Pickpocket was the first film of Bresson’s I saw and I sleepwalked through it. I watched it perfunctorily. Because I had to. It was part of my cinema history education, the one I was giving myself while writing LACONIA: 1,200 Tweets on Film. It was the year I watched 1,000 + films. While watching Pickpocket I was somewhat of a bored pupil. This is not how I typically do things, watch things. What I am referring to here has more to do with a temporary blindness to what I would later come to see as undeniably perceptible. Sometimes blindness is necessary though. It’s not just what you see, as Wim Wenders explained about Pina Bausch and the documentary he would eventually come to make about her (a documentary that took 20 years from start to finish), but when you see.

3. I remember years ago, as a teenager, reading an interview at Saint Mark’s Bookshop in New York, in which the writer Dennis Cooper said that Bresson was his favorite filmmaker and called the director’s work his first communion. This has always stayed with me. I don’t know why. I think the interview was with the writer Robert Gluck, but I also think Cooper has said this to many different people, in many different publications. Like me, Cooper is forever awed (haunted) by what awes him. Bresson himself writes in Notes on the Cinematographer, his aphoristic manifesto, “Images and sounds like people who make an acquaintance on a journey and afterwards cannot separate.” Somehow, at 17, I had the feeling that Cooper liking Bresson would be important for me. This was not a case of idolatry, or an anxiety of influence, but a kind of clue I had stumbled upon for the future (Bresson’s aphorism in Notes on the Cinematographer, “I unconsciously prepared myself” comes to mind here). In some ways Cooper saying he loved Bresson over and over was the thing that interested me most about Cooper, maybe even to this day. Of course as an obsessive and cinephile, repetition, in addition to timing (even when my timing feels off), is one of the ways I come to know/see something.

4. I was so struck by the way Cooper loved Bresson that I kept trying to love him, too. I kept that love in the back of my mind as a revelation I might come to have in my own time. A little over a year ago, I posted this about Bresson and Cooper on my blog, and called it “Agnus Dei,” which means “Lamb of God” in Latin. The Lamb of God is, among other things, used in liturgies and as a form of contemplative prayer. Contemplation being something you do alone and movies being something we historically watched with others.

Agnus Dei

December 1, 2012

When I was a teenager, I used to read about Dennis Cooper loving Robert Bresson and I didn’t understand. Now I am an adult and I do.

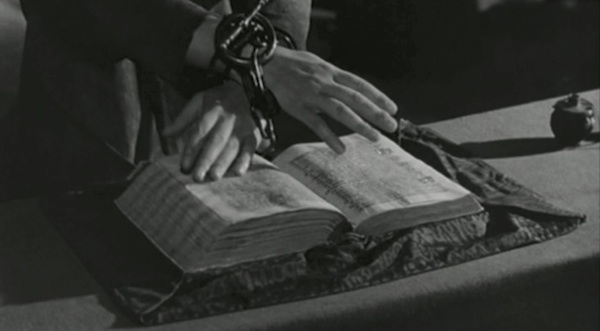

‘IN THE EARLY ’80s, A FRIEND INVITED ME TO a screening of Robert Bresson’s The Devil, Probably, on the condition that, no matter what, I not say a word about it afterward. He claimed that Bresson’s films had such a profound, consuming effect on him that he couldn’t bear even the slightest outside interference until their immediate spell wore off, which he warned me might take hours. He was not normally a melodramatic, overly sensitive, or pretentious person, so I just thought he was being weird-until the house lights went down. All around us, moviegoers yawned or laughed derisively; some even fled the theater. But, watching the film, I experienced an emotion more intense than any I’d ever have guessed art could produce. The critic Andrew Sarris, writing on Bresson’s work, once famously characterized this reaction as a convulsion of one’s entire being, which rings true to me. Ever since, I’ve imposed basically the same condition on those rare friends whom I trust enough to sit beside during the screening of a Bresson film, and I’m not otherwise a particularly melodramatic, sensitive, or pretentious person.’

— Dennis Cooper, “First Communion”

5. I am now like this about Bresson as well, sort of hushed. I am protective of work that I like in general, as in I don’t especially want to share it or talk about it too much, apart from in my writing, and that doesn’t always come easily either. Nor have I ever especially liked going to the movies with other people. I have had only a handful of movie companions in my life and I chose them all carefully. When the Film Forum in New York held a retrospective on Bresson in the winter of 2012, I went with a friend only because he insisted on paying for as many Bresson films as I wanted to see, but both the experience and impression it left on me remained mostly private. I didn’t want to see all of Bresson’s films with someone else. So I saw A Man Who Escaped (1956) (also called The Wind Bloweth Where it Listeth) with him, and the film of Bresson’s I was most struck by at the time, Lancelot du lac (1974), because I wanted to see it — its two lovers and red and green colors — on the big screen. It was a movie I had been writing about in Love Dog at the time and watching on YouTube for weeks whenever I could find it (it is frequently taken down). Lancelot du lac contains one of the most powerful marriages of image/sound in film history, and those are just the opening credits.

6. 2012 was the year I watched all of Bresson’s films. After I saw A Man Escaped at Film Forum, I came home and wrote about the idea of timing, preparation, and emotional endurance by stringing together lines from the film in the book I was writing at the time, Love Dog.

At Each Touch I Risk My Life

January 23, 2012

“In this world of cement and iron.”

“Your door. I’ll try again.”

“To fight. To fight the wall. The door.”

“The door just had to open. I had no plan for afterwards.”

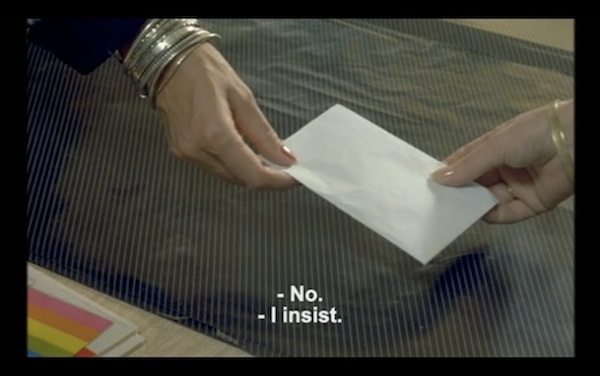

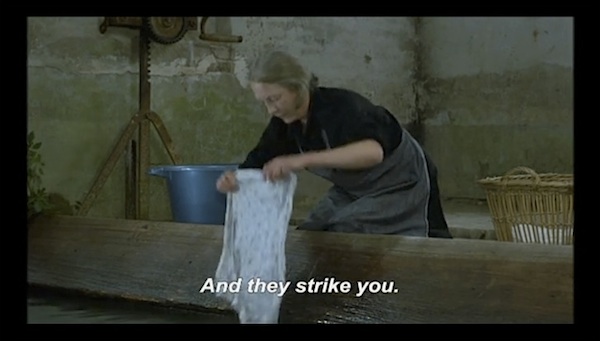

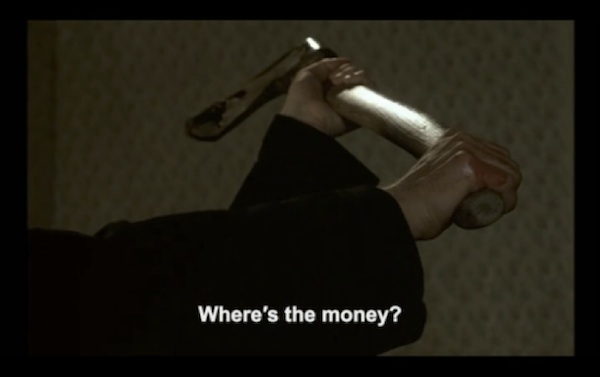

7. In a Bresson film, hands are key. To Bresson hands mean what faces mean to directors like Carl Dreyer and Ingmar Bergman. And what the body means to Tsai Ming-liang and Claire Denis. If in Levinasian terms, ethics begin in the face, which pleads, Do not kill me, the hands do or do not do the killing in Bresson’s films. Answer or ignore the face’s (the Other’s) appeal. In Bresson, hands are mis en scene, often taking up the entire screen, in close-up. The hand is the instrument of ethical/unethical relation.

What we do with our hands…The hand finalizes and seals a deed. Commits one to an act. Sets one on a course. Hands are cause and effect, sending out distress signals. Recall Gena Rowlands flickering hand in A Woman Under the Influence, like a little white flag or SOS. She opens — shows — her hand before she opens her eyes. Hands are give and take. Hold and let go. Hands tell and think and show. They are: how we touch, who we touch, what we touch, how we are touched. Love and hate. Why else would Robert De Niro’s hands in Cape Fear and Robert Mitchum’s in Night of The Hunter feature the four-letter word pair? And Lars Von Trier with the word “Fuck” splayed across his knuckles. In the films of Bresson, without the catalyzing and notational (from Latin notātiō a marking, from notāre to note) hand, there is no life, no consciousness — no destiny either.

L’Argent, 1983

The hand epitomizes human-ness, as Heidegger points out. We choose to be human and inhuman with our hands. We mark the moments we are one or the other, or both. In What is Called Thinking?, Heidegger writes that the hands not only distinguish us as humans different from other species, they are craft, which “literally means the strength and skill in our hands.” If, as Heidegger asserts, “the hand is in danger,” this is never more true than in a Bresson film. Over and over, Bresson uses hands to signal various kinds of danger, irreversibility, and precarity. Hence, if the hand is in danger, so too is our human-ness. The Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh puts it this way, “Love is action and the symbol of action is the hand. When you enter a Tibetan or Vietnamese monastery, you can see a Bodhisattva with one thousand arms. It means the Bodhisattva has one thousand ways of loving and seeing.” Similarly, Rowlands’ playing hand, flashing on and off, is the state of her heart, which is also in a state of emergency.

A Woman Under the Influence, 1974

8. And then there are all the idioms about hands:

Don’t bite the hand that feeds you

Falling into the wrong hands

Trade hands

Take off my hands

Blood on my hands

Wash my hands of it

Playing into one’s hands

Showing your hand

Take someone’s life in one’s hands

My hands are tied

My hands are clean

Putty in my hands

In the palm of your hand

Overplay your hand

I’m in your hands

You’re in good hands

Keep your fingers crossed

9. Bresson quoting Cezanne’s “At each touch I risk my life” in Notes on the Cinematographer equally translates to, At each touch, I risk yours. In L’Argent, Lucien’s hands bursts open onscreen; a signifier of innocence, the unfolding of tragic events (we can see his palm; his (mis)fortune), and an admission of guilt all at the same time. A kind of harbinger, the hand shows what will happen.

L’Argent

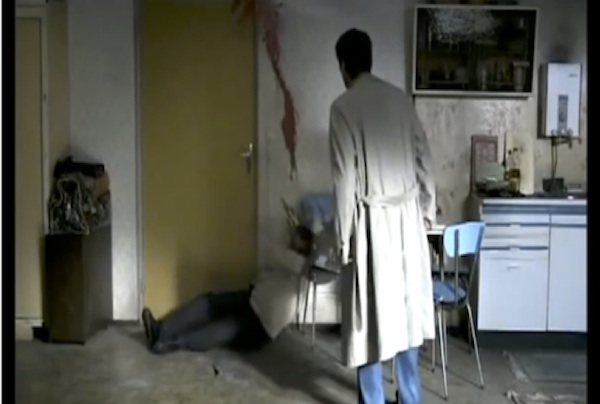

At the end of L’Argent, which has always felt to me like the moment where Michael Haneke’s films begin, Lucien’s hand returns and strikes again, resulting in a final, murderous blow/denouement that is later echoed and revisited by Haneke in Caché nearly forty years later. Both Bresson (through hand shots) and Haneke (through violent blows) let, as Renoir put it, “the unforeseen come into the shot.”

L’Argent

Caché

L’Argent

10. In Love Dog, after watching Au hazard Balthazar (1966) for the first time, I responded to the immolation of Balthazar’s tail and to Marie’s identification with the ill-treated donkey (women and animals, Bresson shows us, endure parallel abuses). Both Marie and Balthazar suffer at the hands of Gérard.

Precarious Life

June 21, 2012

You could love it like this:

Or you could hurt it like this:

For Bresson, these two options — to love and to injure — are not only at the center of Balthazar but the heart of existence. How we (treat) touch something. How something touches us. How we put our hands on something. On Others. How things pass through our hands. Over the course of his life, Balthazar sacrificially passes through a revolving door of love and cruelty.

Animal in Balthazar is ultimate precarity and also ultimate resilience. Balthazar is not only everything that has been historically wounded and subject to malice, exploitation, and domination, but everything (and everyone) that has been made the object of cruelty: Women, animals, the poor, people of color, gay people. Balthazar is literally the Lamb of God. In his book on Bresson, Neither God Nor Master, Brian Price observes, “The animal (or criminal or slave) is capable of making us tremble.”

11. In A Man Escaped, Fontaine’s incredibly deliberate, painstaking, and discerning hands are all over everything. They are the praxis and matrix of escape. They are also his choices, his deliberations, the time spent on things. The time it takes to be free.

Bresson’s careful compositions of Fontaine’s hands recur in other films like Pickpocket, Au hazard Balthzar, and L’Argent. Bresson repeats these arrangements over and over in his filmography. In Cinema 2: Time-Image, writing about what he refers to as “traditional sensory-motor situations” in cinema, Deleuze points out:

It is Bresson, in a quite a different way, who makes touch an object of view in itself. Bresson’s visual space is fragmented and disconnected, but its parts, have, step by step, a manual continuity. The hand, then, takes on a role in the image which goes infinitely beyond the sensory-motor demands of the action, which takes the places of the face itself for the purpose of affects, and which, in the area of perception, becomes the mode of construction of a space which is adequate to the decisions of the spirit.

12. I finally came to Bresson just as I was starting to make homes and refuges out of certain forms in my own work. Like Bresson, I use form to work through form, which is the way I work through ideas. Form is a structure for thinking. I found one home in ascetic modulations of the aphorism, both textual and visual. One such variation and modernization of the aphorism is the screenshot. I have called some of the work I do screen-shot criticism. I wrote LACONIA, a book of 21st century aphorisms on film, before I had read Notes on the Cinematographer, and after only seeing one or two films by Bresson. For this I am grateful. As a presence, he was both there and not there yet. He was the work and the form ahead. I think of form as a way to and through ideas. Form is found. In a piece from Love Dog called “Reunion,” where I discuss Wim Wender’s aforementioned documentary Pina, I chose to frame creative work and the form(s) it comes to take prophetically: “Work is destiny; destinal. It never happens straight…There is the work you make and the work that makes you. The work through which you become — a human being, an artist, a thinker.”

In Notes on the Cinematographer, Bresson refers to this kind of formal precision, discernment, and restraint in a number of ways, “Passionate for the appropriate,” “A matter of kind, not quantity,” and “To know thoroughly what business that sound has there.” Bresson uses sound as something separate from image. When swords pierce through the armored bodies of medieval knights in Lancelot du lac’s green forest, the death cries are almost disembodied sighs of relief. Bresson himself wrote that “while music flattens a surface, makes it into an image, sound lends space, relief.” In Bresson, Freud’s the work of mourning becomes the work of working out a form. As Susan Sontag points out in her 1964 essay on the filmmaker, “Spiritual Style in The Films of Robert Bresson,” form — the right form; the right form for a particular problem, situation or idea; the right form for a particular artist — is Bresson’s subject and substance (The jury is still out on whether this can simply be called style, as style is both affected and deeply personal). Careful calibration of form in Bresson is also a way through suffering and injustice. Working out a form (working anything out) is one of the ways in which style becomes both “spiritual” and political in Bresson’s work.

Lancelot du lac

Sontag:

Why Bresson is not only a much greater, but also a more interesting director than, say, Bunuel is that he has worked out a form that perfectly expresses and accompanies what he wants to say. In fact, it is what he wants to say…And the form of Bresson’s films is designed (like Ozu’s) to discipline the emotions at the same time that it arouses them.

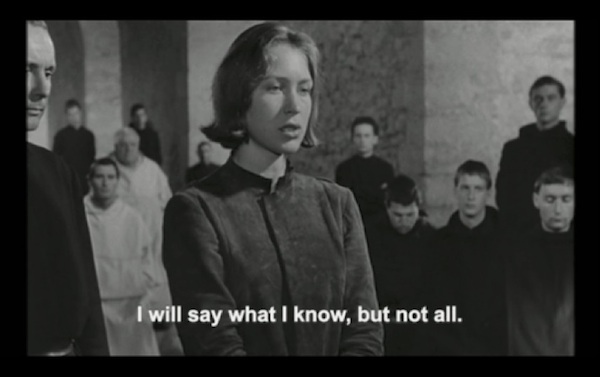

Indeed, gradually working out a form of escape is how Fontaine succeeds in escaping from prison in A Man Escaped. Escape is a form that Fontaine masters over time, resulting in corporal and spiritual release. His hands stand for method, deliberation, duration, endurance. In Bresson’s procedural The Trial of Joan of Arc (1962), the form is a resistance to form, which is the trial (or process as its called in French) itself. Joan’s method is to not submit to the form (system) of coercion that is inflicted upon her by the church. Her form is restraint, resistance, internal fortitude, religious conviction — how she does and does not proceed. While Carl Dreyer’s film about Joan of Arc puts passion and emotion (Joan’s suffering, Joan’s sacrifice, Joan’s crying face) at the center, Bresson, whose screenplay is drawn from the minutes of Joan’s actual trial, makes the trial the focus. Another notable difference between the two versions of Joan of Arc is the part of the body that is filmed and underscored. For Bresson it is Joan’s hands, for Dreyer the trial is famously in Maria Falconetti’s exquisitely performative face (Bresson hated Dreyer’s film). The trials of Joan, Fontaine, Mouchette, and Balthazar, to name a few, and the internal/external forms of suffering and transcendence that Bresson assigns and arms each of these characters and films with, is what I think Deleuze means by “decisions of spirit.”

The Trial of Joan of Arc

Screenshots by Masha Tupitsyn

+++