Earlier in the month I posted one story from my novel-of-sorts based around the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing 易經; and I thought I would follow it up with another. It is one of the stranger stories from the book, and is about fox spirits, ghosts and other such matters.

Earlier in the month I posted one story from my novel-of-sorts based around the sixty-four hexagrams of the Yijing 易經; and I thought I would follow it up with another. It is one of the stranger stories from the book, and is about fox spirits, ghosts and other such matters.

Fox spirits or hulijing 狐狸精 are common in Chinese folklore, where they are often said to take human form and to seduce human beings. In South China, they are also associated with the curious folk illness known as suo yang 縮陽, literally “the withdrawal of the male principle”, which causes the sufferer to believe their penis is receding into the body, where it may cause death. There are various remedies for this unpleasant ailment, including the banging of gongs, the consumption of ginger soup, and an exorcism performed by a Daoist priest.

This story that follows begins with an encounter with a fox. The fox comes from the Yijing itself, and the text associated with this hexagram is almost hallucinatory in its strangeness: foxes, cart-loads of ghosts or demons, mutilated captives.

I read and re-read this text on the train whilst travelling to Tianshui in Gansu province, where I was planning to visit the Fu Xi temple. That night, in the hard sleeper compartment, my travelling companions on the lower bunks cooking up instant noodles at two in the morning, and suffering slightly from a fever, I had strange, troubled dreams. Some time in the middle of the night, convinced that I was being tugged at by invisible, ghostly hands, I woke up shouting.

The following morning I felt wretched. I washed as best I could, drank a little tea and jotted down the story below. The images come straight from the hexagram. The song is a children’s song known by children throughout China, and sung to the tune of Frère Jacques. It is the kind of thing that echoes around your head during unsettled dreams:

兩只老虎, 兩只老虎

跑得快,跑得快

一只沒有耳朵

一只沒有眼睛

真奇怪, 真奇怪。

Two tigers, two tigers

Run away fast, run away fast,

One has no ears,

One has no eyes,

Very strange, very strange.

+

It happened one night when I was making my way home along the path through the forest. The air was thick with the scent of pine needles. I could see the lights of the university buildings down by the bay, reflected in the water. The night was warm, and I was sweating a little with the exertion of the climb. I was alone, thinking about a girl: back then, there was always a girl I was thinking of, with an intensity that was more than carnal. Carnality is something I have learned in my old age; it was not something that I knew in my youth. Now, I presume, she is married, with a child perhaps, a husband who puts on a shirt and tie in the morning, who kisses her in the evening. As for me, I live alone, with my thinning hair and my weariness.

It was then I saw the fox, slight and quick and orange between the dark pines. She moved with such suppleness that I stood and stared at her, momentarily astounded. She paused and looked back over her shoulder, and I followed. I stepped into the pines. I knew the woods well, and was confident I would find the path again. When she saw I was following, she trotted a little way, then paused, then trotted, then paused, as if leading me on.

After we had gone not more than one hundred yards, she started to trot faster. I quickened my pace. The trees became thicker, the university lights dwindled to nothing, and all at once I was lost. I hesitated, looked back, realised that I had no idea where I was. When I turned once again, I saw that the fox had slipped away. I stumbled on a little further. Ahead of me the trees became thinner. I could glimpse moonlight. There was a smell, somewhere, of burned meat and incense.

I emerged from the trees onto a road that I did not recognise. It was paved with stones and covered with a thick mat of almost luminous moss. I could still smell the charred meat and incense, some way off. I looked around for the fox, but she was gone.

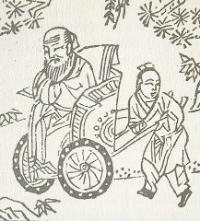

It was then I heard the creak and the rumble of cart-wheels. I looked down the road and saw a wagon. It was like the ones I knew from picture books in my childhood, hauled by six figures, who strained at the ropes as the cart shuddered down the road. But my attention was drawn by the passengers. There were seven of them, and they were somehow insubstantial. It was not that they were translucent, exactly; it was just that the light seemed to hover around them like a fine mist, as if they were seen through smeared glass. And they were singing. The words were unfamiliar — liang zhi lao hu, liang zhi lao hu, pao de kuai, pao de kuai — but the tune took me back to childhood. As the cart drew closer, I noticed that the figures pulling it were naked and thin, their backs marked by the dark lines of the lash. The passengers were drinking something from a flask that they passed anti-clockwise. Occasionally one leaned forward and with a whip snapped at the backs of those who were pulling.

I stepped towards the shadow of the trees as the cart rumbled to a stop in front of me. One of the passengers leaned out. Even this close, it was hard to bring these insubstantial figures into focus.

“Cart or horse?” asked the figure, and I saw that he was looking straight at me.

I hesitated.

“Cart,” he said, pointing to a space within the cart, “or horse?”, pointing to the others like me.

I could see the naked figures staring at me, but I didn’t meet their eyes. I hesitated. “Cart,” I said at last. “Cart.”

The naked figures turned away. Immediately I felt ashamed.

I climbed into the cart. One of my fellow travellers cracked the whip. The wagon creaked away. The song recommenced: liang zhi lao hu, liang zhi lao hu, pao de kuai, pao de kuai. Immediately I regretted my choice. “Horse,” I wanted to say, “Horse.” But it was too late. The cart was moving on, the bottle was being passed. There was nothing I could do other than drink. So I drank and drank until I was blind drunk; and because the groans of those pulling the cart were too terrible to listen to, I joined in the singing so I did not have to hear.

At some point I passed out. The following morning I woke by the side of the path that I had left the previous evening. I sat up and looked down at the university buildings on the bay. The sun was coming up, and I was cold. I could still hear the song from the night before, liang zhi lao hu, liang zhi lao hu, pao de kuai, pao de kuai.

I walked back down to the university campus. By the afternoon the hangover had already subsided; but the song and the shame have remained.

And so this is how I live: alone, with my thinning hair, my carnality, my weariness and my regret.