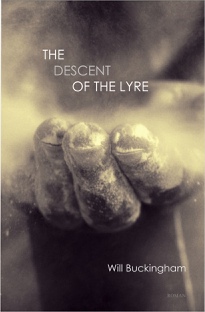

My novel, The Descent of the Lyre is due out in the summer of 2012 from Roman Books. It is a book about Bulgaria, banditry and guitar music, set in the early nineteenth century, and draws on Bulgarian folklore and history, and echoes of the tales of Orpheus (who is reputed to come from the Rhodope mountains of Bulgaria). I thought that I would post an extract here on Necessary Fiction to give a flavour of the book. The passage comes from the early part of the novel, where the father of Ivan Gelski—the novel’s protagonist—goes to the monastery church of Bachkovo in the Rhodope mountains, to ask the Virgin Mary to intercede on behalf of his son, who has been wounded in a raid upon their home village.

My novel, The Descent of the Lyre is due out in the summer of 2012 from Roman Books. It is a book about Bulgaria, banditry and guitar music, set in the early nineteenth century, and draws on Bulgarian folklore and history, and echoes of the tales of Orpheus (who is reputed to come from the Rhodope mountains of Bulgaria). I thought that I would post an extract here on Necessary Fiction to give a flavour of the book. The passage comes from the early part of the novel, where the father of Ivan Gelski—the novel’s protagonist—goes to the monastery church of Bachkovo in the Rhodope mountains, to ask the Virgin Mary to intercede on behalf of his son, who has been wounded in a raid upon their home village.

I will be posting on my own site willbuckingham.com when the book is eventually published.

+

Not long after, the summer started to turn to autumn and a chill came into the air. The festival of Golyama Bogoroditsa, the feast of the mother of God, came round; and the boy’s father— because his son’s wound was still livid and he burned with a fever—set out across the mountains to make offerings at the monastery of Bachkovo. He took with him a cheese in a cloth and some bread, and walked for three days, sleeping where he could, drinking from the forest streams. He had no horse or cart to carry him, and he went on foot away from the major paths, crossing upland meadows that were blooming with flowers. He feasted without joy on the berries that hung from the black brambles. At night he lit small fires to keep away the wolves and the bears. And at last he arrived at the monastery, emerging from the mountains onto the road that led up to the shrine.

The feast day was the following morning, and the road was crowded with pilgrims. Traders were selling griddled fish and bread, bundles of medicinal herbs, charms and forged relics. On that particular morning, one could have bought as many as seventeen thumbs of Saint John the Baptist. Ivan’s father had only a few coins in his pockets, and the crowds made him uneasy. Somewhere, a little way off, he could hear the bleating tones of a gaida, the bagpipe that wailed like a lost sheep on a hillside crying for its mother. Ivan’s father lowered his eyes and pushed through the crowds, following them up the hill until he came to the threshold of the monastery. He bowed his head and entered the courtyard.

Inside it was less a peaceful sanctuary than a rowdy marketplace, monks and dogs scratching themselves in the sun and in the sight of God, hawkers selling candles and phials and ikons. A long line of pilgrims stood, waiting to be admitted to the church. Not knowing what else to do, he asked the last in line, ‘Tell me, where might I find the Virgin?’

The man smiled amicably. ‘She waits inside,’ he said. ‘You must simply join the line. Tell me, have you come far?’

Ivan’s father mumbled the name of his village, but the other man had not heard of it. Many of the pilgrims were well-dressed, and for a moment Ivan’s father felt ashamed of his clothes; but he reminded himself that God is interested neither in the fabrics with which the body is clothed nor in the flesh with which the soul is clothed, but He cares only for the soul itself, whatever that might be, wherever it might be found.

Ivan’s father had been to the shrine once before, when he himself was a boy. It was grander than he remembered, and richer. The monks wore clothes more opulent than before. When he visited as a boy, he ran through the courtyard shouting, sending chickens flapping off in squawking flurries. This time, things were different. His hair was grey. There was no joy in him. He kept his head down, not pausing to gawp at the people and paintings. His thoughts were only of his son.

The line shuffled forwards, and before long, Ivan’s father had stepped out of the sun and into the narthex. He could hear the intoning of liturgies from inside the nave, could smell the thick scent of the incense. I know nothing of religion, he told himself. I am unlearned in books and scriptures. I do not know the ways of God, nor would I recognise him if I met him upon the hillside.

As he entered the church, the smell of the incense became stronger, catching at the back of his throat. Why must God smell like this? he found himself thinking. Why can he not have a good, clean smell, like the smell of fresh cheese, or of the meadows in summer? Why this thick, sweet darkness? Then he looked up and gasped, because the interior of the church was both wonderful and terrible. The liturgy murmured around him in call and response, the priest behind the iconostasis took the lead and hidden voices replied. The icons glowed in the light of a hundred candles. And although he could not read the words, the pictures spoke to him. He saw Saint John, that fierce and unruly angel of the desert, his body covered with a thick pelt of hair like an animal, broad wings stretching from his back; he saw Dimitar and Georgi on their horses, Dimitar about to deal the death blow to a human adversary, Georgi about to dispatch a dragon (but why? he asked himself. He could not remember). He saw the Virgin and the Christ-child, and was reassured that the Mother of God would surely help him, for she had lost her son, as he feared he might lose his, and if there was any saint who would understand the anguish of such loss, it would be the Virgin.

Then he was standing before her, the Virgin Mary Eleusa, her features in shadow, only the silverwork glinting in the flickering light of the candles. Three steps led up to her, and the man in front of him was leaning his forehead against her, making an offering. Ivan’s father waited for him to descend, and then he himself climbed the steps. Only a foot away from the Virgin, he could still not make out her features. He touched the silverwork, peering into the shadows to see if he could see the lips of the icon move, then he reached into his pocket and laid a coin in front of her. He looked the Virgin in the eye, for it is a weak man who cannot look a woman in the eye, and he spoke to her, under his breath. I give you my son, he said. If you only cure him of his sickness and his fever, I give him to your keeping. And may you and the holy saints do with him what you will.

Mary did not respond, but nor did she look away. Behind him, the people standing in line were becoming restless. Somebody muttered he should move on. There were people waiting. Ivan’s father lowered his gaze. He turned away from the Virgin, and saw the light piercing the dome of the church in great shafts that swirled with the smoke of incense, and there were tears in his eyes. The drone of the liturgy and the exhaustion of his three day trek to the monastery, the crowds who were pressing on all sides, the incense-sweetness that was the smell of God, too sweet for him, a rough man of the mountains—all these pressed upon him with such force that he swayed on the steps as he descended, and were it not for the kindness of the other pilgrims, he would have collapsed altogether.

Those kind people led him back into the sunlight, and sat him down to catch his breath. There were tears on his cheeks, which he wiped with his sleeve. Beyond the murmur of the liturgy, he could hear the mournful bleat of the gaida, a long way off. And then, because everything he had come to do he had done, he rose to his feet and left the monastery, fleeing the crowds and market-traders and revellers and pilgrims as he headed up the path back into the mountains.

He did not stop until he was sure he was alone, and there he drank cold water and ate fresh blackberries. He looked in his pouch. There was still a little bread, and cheese enough to sustain him. Perhaps, he thought, when I return home, the Virgin will have had a chance to act. But he was worried. There were so many petitioners. The Virgin could no more be expected to respond to every prayer than she could be expected to attend every wedding. With this melancholy thought, he started on his way back home.