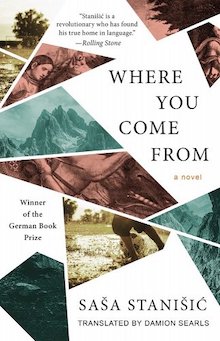

Tin House Books, 2021

In Where You Come From, Saša Stanišić rifles through the prose writer’s toolbox, deploying autofiction, fable, metanarrative, lists, and choose-your-own-adventure to compose a complex story of memory, identity, politics, and exile from a nation that no longer exists. The novel follows a protagonist named Saša Stanišić as he flees Yugoslavia with his family and they settle in Germany as refugees. Running parallel to that story is a present-day narrative in which his paternal grandmother, Kristina, begins to lose her memory and with it, the narrator’s living link to his own past. Like Paul Celan who, in his famous poem “Todesfuge,” used elision and distortion to conjure the horror of the Nazi concentration camps, Stanišić knows that some experiences are best explored indirectly, using techniques of fragmentation and reassembly, despite the risk to the coherence of the whole.

Each chapter in the novel bears a descriptive title that hints at the story to follow, like “Little Check Marks on Our Names” or “Bruce Willis Speaks German.” Self-contained but strategically contributing to the whole, these chapters explore in vibrant detail life growing up as a refugee in Germany: afternoons spent at the ARAL gas station in Emmertsgrund that was “our youth center, drink supplier, lottery-ticket seller, dance floor, toilet,” leaping the fence of the wastepaper dump to read magazines, spending Saturdays playing role-playing games, a first kiss that tastes of kofta (a meatball dish), and, of course, dealing with countless large and small prejudices and insatiable bureaucracy. The chapters also catalogue the important people in Stanišić’s life: the father who arrived in Germany with “a brown suitcase, insomnia, and a scar on his thigh”; his mother, who studied Marx in Yugoslavia and in Germany worked in an industrial laundry so hot “her heart boils”; his maternal grandmother, Mejrema, who tells the future from kidney beans; his friend Dedo, who fled Bosnia by riding a tractor trailer through a minefield and “can go to sleep only by shaking his head quickly back and forth”; and Gavrilo, one of the oldest men left in the small, rural village of Oskoruša, who wants Stanišić to know where he comes from. Occasionally, the chapters return to Yugoslavia, for a soccer game with the Red Star Belgrade or a Youth Relay celebration. In “Oskoruša 2009,” the chapter that weaves all these threads together, the protagonist and Grandmother Kristina take a trip to Oskoruša, where only thirteen people remain, in order to eat and drink at the Stanišić family graves. Above them, a poskok watches—a snake of memory, of language, of terror. Occasionally in these sections, the war looms and future violence stains the narrative, showing through.

Further fragmenting the fragmented narrative is the novel’s approach to time. Early on, the narrator says:

You find yourself in the strange, dimly lit cave of time. One passageway curves downward, the other leads upward. It occurs to you that the one leading down may go to the past and the one leading up may go to the future. Which one do you decide to take?

The novel shoots the reader up and down this chronological passageway. One chapter unfolds in 1986 while the next is set in 2018. Within chapters, too, the narrative may leap forward or backward with an image, a word, or a memory. Speaking of Grandmother Kristina, the narrator says “a veil of The Past has covered her Now. Fictions are woven into it.” Both memory and perception are unreliable: “It’s impossible to tell if she’s really remembering something or making up stories.”

The novel functions in much the same way. It is impossible to separate memories from made-up stories, and the narrator will occasionally step in with commentary that further rattles the reader’s certainties. The narrator describes his father laying down miles of pipes at BASF Chemical in former East Germany:

The pipes were so big that he could stand up straight in them. By the end of the day, he and his coworkers had sometimes laid several miles of pipes. And when they didn’t feel like walking back, they would just lie down and go to sleep, and the early shift would bring them sandwiches in the morning.

In the next paragraph, his father undermines this confident description: “Nonsense. It wasn’t like that at all in Schwarzheide. The pipes weren’t that big, and no one ever spent the night in them, and in general: ‘Just ask so you don’t have to make things up.’”

Occasionally, the narrator will step in to make semi-didactic statements on the nature of identity:

Conformity was my rebellion. Not conformity to the expectations people in Germany had of how immigrants should be, but also not intentionally against it. My resistance was directed against the fetishization of where a person came from, against the specter of national identity. I was for belonging. Wherever people wanted me and I wanted to be.

While these moments signal a familiar youthful rebellion against familial obligations and defiance of the bureaucracy represented by census forms, they also, and more importantly, forestall simplistic conclusions about identity, politics, and refugees that veer toward kitschy sentimentality or treacherous nationalist stereotypes.

At the heart of this vast and multifaceted narrative is Grandmother Kristina. Like the mighty Drina, she is the fast-moving, occasionally overflowing, river that unites the book’s disparate fragments. She both begins and ends the book, where the narrator ultimately comes from: “memory and imagination.” In the final choose-your-own-adventure section, many of the foundational images, certain lines of dialogue, and the narrative strands converge in a wholly satisfying way. It doesn’t take long to read through the multiple endings, and each ending brings the book to a convincing close.

As distressing images pour from the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, this book is a timely antidote to poisonous political blame-games and sneering statements about the plight of refugees.

+++

+

+