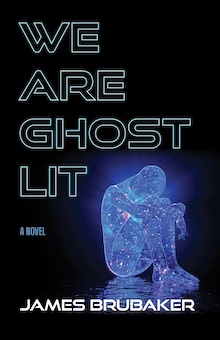

Braddock Avenue Books, 2023

At its heart James Brubaker’s We Are Ghost Lit asks a simple question: What is grief for one lost life?

Wrapped in cultural allusions, from Star Trek on the pop side to Borges on the literary, with a minimalist playlist for grief in the art-resisting mourning of Phil Elvrun, We Are Ghost Lit balances obsessively emotional realism and compulsive literary deflection with the fabulist invention of cosmic entities—the Starman and the Universe, along with a few Black Holes—who, despite the very human sincerity of the many James Brubakers narrating the novel, tend to steal the show.

The novel opens as the Starman is born “and stares into the cosmos surrounding him.” Starman’s first moment of existence “is every moment of all existence.” After a brief bout of disorientation, in the midst of his first encounter with the apparently all-knowing Universe, the Starman “looks for his origin, but he cannot see it because from the moment he was born, he always was. It’s a strange paradox—he remembers waking up for the first time having always already existed.”

The Starman has questions. “What am I?” he asks. “Why am I here?” When the Universe fails to help answer them, the Starman turns his attention toward Earth. Many twisty plays of time and space are eventually followed by a down-to-earth human narrative, born in grief, as a character named, like the author, “James Brubaker” addresses a friend who has died mysteriously, possibly by suicide, possibly by overdose, possibly at another’s hand.

This Brubaker (the first of several) is struggling, trying at once to face his grief and to turn away from it. In doubt about everything he knows about his friend’s death, he constructs and rejects alternative scenarios, invoking their past together, from childhood Star Trek fandom roleplaying Spock and Kirk, through lives as young men in college, finally as old friends catching up two or three times a year.

A second Brubaker arrives. He is a construct who knows he’s a construct; he also knows the first Brubaker is also a construct. As he questions everything the first Brubaker is up to, and everything he himself is up to, there are deliberate echoes of the Borges (or Borgeses) of “Borges and I,”a playful short story that provides the literary counterweight to the main narrative’s cosmic constructs.

All this architecture, however, is mostly smoke and mirrors with which Brubaker entertains his readers while propelling them through the novel’s unexpected twists and turns. These hijinks also, and perhaps more importantly, protect a third character named James Brubaker. This character, who is described as the “real flesh-and-blood James Brubaker,” shows up late in the book in order to narrate within ellipses as he confronts his grief, guilt, and confusion at the death of his friend.

Because, if we take the writer at his word despite his many encouragements not to, there really was a “beloved friend” who died, probably by suicide, and the grief of this loss and uncertainty is the source of the novel and its several narrators and slippery cosmologies. Nothing in the narrators’ claims and disclaimers is likely to satisfy the truly human James Brubaker by clarifying or relieving or releasing his grief. The friend remains lost, and ultimately the book itself may be a question without an answer. That is, the book asks not only what is grief, but what is its value if transformed?

From the start We Are Ghost Lit makes clear its mistrust of the transformation of grief through art, and yet as Brubaker masterfully constructs and deconstructs form to reflect meaning, even while dwelling in his grief and questioning the ethics of aesthetic transformation, exactly this transformation is the journey the novel takes.

The story’s underlying narcissism is indirectly acknowledged by the Borgesian narrator-in-brackets early on:

I know, I know—we’re working toward understanding the essence of our dead friend, of getting to the core of the idea of him. But that strikes me as frivolous, a way to prolong mourning while actively deferring a meaningful confrontation with grief. And that’s not saying anything about how solipsistic the novel feels in a time of great social upheaval. Is this really a time to not just turn, but intently stare inward, to obsess over a dead friend when there is so much more important work in need of doing in the world?

When the novel finally takes its surprising turn toward happiness, the solution it offers is ultimately a meeting with the self. But it remains unclear whether this meeting expresses wise self-acceptance and self-knowledge or is merely a surrender to narcissism, a solipsistic embrace of the self to the exclusion of all others.

More than a chronicle of solipsistic obsession, We Are Ghost Lit is a cosmic near-fairytale, a once-upon-a-time for an age of suicide and overdose, both personal and global, it is a cautionary tale, a warning—don’t fuck with the universe.

Is dwelling in grief a self-indulgent exercise or is it an act of generosity insofar as it effects, through imagination, a rebirth of the lost life? To answer this in the novel’s terms would lead to spoilers. Instead there is this insight, discovered by the Starman well before the action is complete:

Outside of linear time, all humans are always alive, always unborn, and always dead. But they’re always alive. Poor mortals! They exist forever but their perception is too limited to know it!

This vision of immortality must be asserted for the writer too—the living writer, not the written one. The point of “Borges and I” is that, like the Starman himself and his final, elliptical narrator, the living writer always and inevitably escapes the page.

+++

James Brubaker is the author of Pilot Season, Liner Notes, and Black Magic Death Sphere: (science) fictions. His work has appeared in Zoetrope: All Story, Michigan Quarterly Review, Hobart, Booth, and The Collagist. He lives in Missouri with his wife and cat, and teaches writing there.

+

Catherine Gammon‘s new collection, The Gunman and the Carnival, is forthcoming in 2024 from Baobab Press. She is also the author of four novels: The Martyrs, The Lovers; China Blue; Sorrow; and Isabel Out of the Rain. Find her @nonabiding on Substack and Bluesky.