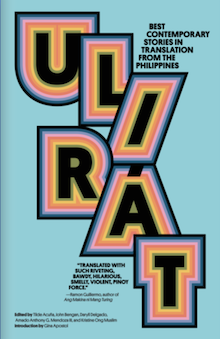

Gaudy Boy, 2021

Most Filipinos know at least four languages — English and Tagalog, the two official national languages, plus legacy Spanish and a more localized language (or two or three). This multiplicity is aptly represented in Ulirát, an unprecedented collection of short stories that includes translations from seven of the more than one hundred languages of the Philippines. Each language represents a community with its own mystical spirits and inside jokes, and an identity not fully captured by the word “Filipino,” and each story in the collection offers a unique take on those communities.

The linguistic multiplicity of the Philippines provides fertile ground for puns and other wordplay. So fertile, in fact, that even Gina Apostol, the brilliant Filipino-American novelist who provides the collection’s introduction, occasionally had to guess at the linguistic puzzles deployed by the contributors. For Apostol, these moments are sources of wonder:

There is a Waray word we used to say with great fun as kids, pachis, that’s long puzzled me… The –ch sound is not really in our alphabet. It often indicates a foreign origin. It was only as I researched the Philippine-American War that I understood. Pachis in Waray is a humorous, childish word for enemy, or betrayer. It comes from America: Apache.

Such sublime moments of discovery and connection, shadowed by horrifying historical backdrops, are what Ulirát offers on virtually every page.

For the culturally unfamiliar reader, Ulirát is an education. For instance: teks cards — with their cool, comic-like designs — are popular with children in the Philippines, who throw them into the air and guess which side will land facing up. Calamansi is a sour citrus fruit that, according to Wikipedia at least, is a hybrid between kumquats and “probably” mandarin oranges. Aswangs are shape-shifting mystical beings. A suyod is a fine-toothed lice comb. Carabaos are a type of water buffalo.

But cultural novelties and instances of sly wordplay are hardly the whole story. The writers of Ulirát blend folklore with tropes from the Western canon and brutal colonial history. Layers of references to different times and colonial regimes stack like sediment, threatening to bury the verbal fun and games. There are no fairy tale endings, just the effects of serial colonization and downstream capitalist economics. In “Voice Tape,” a mother lives in a different city than her family in order to pursue a middle-class opportunity; her experiences permit readers to see how American gatekeeping and bullying translate in other places. “[Her] voice […] in the recording was clear despite her muffled sobs: ‘Forgive me, Dear. I did not want this. They’ll kill me if I resist. Just think of the bright future ahead of us and our children. . . . My contract will be over soon.’”

Beyond economics, no story confronts its Western influences and their inescapability as directly as Roy Vadil Aragon’s “I am Kafka, a Cat,” which features a narrator who turns into a cat:

This is probably what I get from reading too much fiction, especially those of the magical realist and fantastical subgenre; the works of Kakfa, Murakami, and Gaiman; and of stories about cats. Perhaps I am now in a situation that most people would describe as Kafkaesque. But why be so literal about it? Is there really anything magical about my situation?

As with the wordplay described earlier, this tussling with Western literary canon is simultaneously tongue-in-cheek and barbed. The storyteller, lost in his Kafkaesque narrative, forsakes his identity and literally takes on the name of his creative forebear: “Kafka, a cat, that’s me. Kafka is more suitable than Ranilio — the name I was baptized with, my dad’s name — and my surname Callautit.” From that point, the narrator’s past identity is discovered to be meaningless within the hierarchy of local street cats. The allegory neither satirizes or contrasts the harsh realities of the human world, but simply holds up a mirror to them, crystallizing the oppressive brutality to which all these writerly fireworks ultimately refer: “Yes, of course, there is also racial discrimination among cats. If you’re a native cat who is ugly and scrawny, you have no right to live. No one will buy or pay for you… The Philippine cat truly arouses pity — it has no worth in this world.”

In a couple of stories, whimsy outweighs devastation. In “The Three Mayors of Hinablayan,” a memorable communal narrator affably shares the story of three mayoral candidates who each pick a reason why they deserve to win the election. Then they each proclaim the equivalent of “The other guys lost! No takesies backsies!” and attempt to wait out their opponents. It’s a stalemate where everyone loses, , which to many contemporary readers, will work perfectly as an absurdist political satire.

Ulirát, which is Tagalog for consciousness, provides a sharp and balanced look at the unique cultures of the Philippines and their myriad forms of survival. The collection’s emotional depth would be overwhelming were it not for the indelible joy these writers take from aswangs, carabaos, and other details of everyday life. In assembling a more comprehensive picture of Filipino consciousness, the collection proclaims the strength of the archipelago’s diversity of cultures and perspectives. Ulirát gives English readers an opportunity to pay attention.

+++

+

+

+

+

+