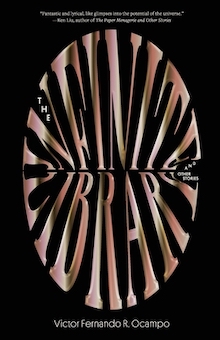

Gaudy Boy, 2021

For the diasporic characters in The Infinite Library and Other Stories, the library and its infinite potential symbolize a visionary escape into a kind of afterlife where polyglotism and complex transnational backgrounds are inevitable facts. Victor Fernando R. Ocampo’s collection is simultaneously a meaningful addition to the genre of speculative fiction and a powerful manifesto laying out the possibilities of Southeast Asian literature.

Although each of the collection’s eighteen stories can be read as a stand-alone, all exist in the same universe. One story’s narrator will pop up as a footnote in another story. The Cafuné brace — a telepathic device in the brain whose name derives from a Portuguese word meaning “to brush a hand through a loved one’s hair” — appears multiple times. Like a good mythology, the collection is ordered carefully, so each story builds on those preceding it.

Ocampo, who is Filipino and has lived in Singapore since the early 2000s, expertly wields the multiplicity of a modern transnational identity, making it a boon to the short story form. His narrators inhabit manifold time periods, nationalities, languages, and sexualities. He stretches the boundaries of the short story by deploying techniques that are epistolary, academic, and poetic. And he explores the possibilities of the Filipino diaspora, whether in an alternate timeline, across the world, or in space.

Ocampo refuses to dilute his compelling universe by explaining it to an outsider audience. A dozen languages pepper the stories to dizzying effect; he also draws on kaomoji (Japanese emoticons) and l33tspeak. For readers unfamiliar with the history, food, or languages of the Philippines or Singapore (or Catholicism, for that matter), appreciating the stories will involve Googling. But for those who engage actively with the text, rewards await, each one rich as a slice of pan de coco.

“Mene, Thecel, Phares,” the opening story, reimagines the life of Filipino writer and activist José Rizal, who was executed in 1896 by the Spanish for his anti-colonial writings. The narrator moves to Germany to avoid persecution, only to feel there “the oppressive insecurity of a brown body in a sea of infallible white.” Ocampo ends the story in three different ways, provoking the reader to wonder whether, in a parallel universe, Rizal might have lived a different ending for himself.

A clear standout is “I m d 1 in 10” — translation: “I Am the One in Ten” — written almost entirely in l33tspeak (you actually get used to it). The narrator and his parents work their entire lives so he can leave home and make it into one of the utopic “New Cities.” The journey is fueled by self-delusion. In one scene, he breaks up with his boyfriend after polling his social media network. The poll results encourage a conformist lifestyle based on social climbing:

My survey said d@ I shld dump my boyfriend, which I did d@ same evening. He tried in vain 2 tell me hoW much he <3d me but somehoW d@ wasn’t worth as much 2 me anymore. I needed 2 prove 2 myself d@ I could b like every1 else. I quit <3 cold turkey. Still, my ex didn’t understand what happened. He made a very public, very n00b threat 2 take his life. Un4tun@ely 4 him, I was already plugged in 2 my new social world. All I wanted now was 2 b part of d SWARM.

Although the narrator feels guilty upon learning of his ex’s suicide, he convinces himself that everyone has to make their own choices and moves on. This confidence proves unfounded. After finally achieving the dream of moving to a New City, he realizes that he is wholly expendable. As an allegory of Asian immigration to the West, in which immigrants sacrifice familiar routines and traditional values only to find that they’re considered subhuman, the story is painfully spot-on.

In the Delaney-esque “Brother to Space, Sister to Time,” three siblings hurtle toward a black hole. Their home is in danger, and they are fighting an enemy that poisons their minds, turning them against each other. The spaceship action can be tricky to follow, but the pieces come together in two endings. One is written from the narrator’s fantastic perspective while the other is from the perspective of the more sober siblings. Both are equally moving. The reader is left with the mournful sense that some families dole out both love and pain in equal measure.

Although each story contributes to the lore of the Infinite Library’s universe and presents speculative food for thought, there is some unevenness in the collection. “How My Sister Leonora Brought Home a Wife” feels incomplete, with most of the story told in the title. “A Secret Map of Shanghai” waxes poetic on the intersection of colonialism and the body but teeters on the brink of orientalism. “Dyschronometria, or The Bells Are Always Screaming” explores the concept of temporal loops through intriguing vignettes but relies heavily on the cliché of the yelling, religious mother.

This is a reader’s book through and through, and the final story, a two-page ode to reading, confirms it. “To See Infinity in the Pages of a Book” provides a lovely cap for a work that has reveled in impossible libraries. Sometime in the future, a crack in spacetime reveals an astronaut literally “falling into a good book”:

Inside the singularity, the impossible astronaut is not dead, they are reading. Before they get to that last book they will ever read in their life, there is yet another book that needs to be read. Between that penultimate book and the one they hold in their hand, there is yet another book and another demanding attention. In fact, between the astronaut and Death, there is an endless series of books with no beginning and no end.

The scene is a literary imagining of a mathematical limit, in which a line stretches infinitely toward a value but never quite arrives. Usually it is the writer who achieves a kind of immortality. But Ocampo shifts that power by bestowing it upon his readers. The story closes with the optimistic declaration that “those who fall endlessly into books never die. They are forever reading.”

+++

+