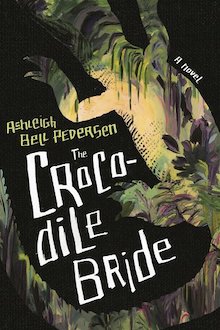

Hub City Press, 2022

One description of Ashleigh Bell Pedersen’s debut novel, The Crocodile Bride, might begin: Sunshine Turner lives in the town of Fingertip. Without knowing more than this, a reader can’t help but consider the metaphoric possibilities. Sunshine: a joy, a light to cure the darkness, a vital ingredient to life. Turner: someone who changes course or causes a shift. Fingertip: the end point, a nexus of sensation, an indicator.

Pedersen’s choice of names is no accident. The Crocodile Bride thrives on metaphor, on figurative language, and on stories that represent truths too difficult to speak directly. The layering is so rich, the slipstream from metaphor to reality so seamless, that at points in the novel, the reader might be confused as to whether they’re reading the “real” narrative, or the stories-within-the-story. By the end, the line between the truth and the stories seems to have blurred.

The novel unfolds primarily during the summer of 1982, when Sunshine, approaching her twelfth birthday, senses trouble: she feels stones in her chest. Further portents of calamity include dwindling food and cash at home; the impending move of her closest friends, her Aunt Lou and cousin J.L.; and the “storms” that her father Billy brings home ever more frequently. These storms, worsened by Billy’s heavy drinking, sometimes awaken “spiders” — his hands, roving unpredictably. Seeking explanations, Sunshine turns to symbols and stories:

Later that summer, Sunshine would decide that the stones were to blame for all that happened. They were, she would eventually see, the first of several curses. She would connect the signs she had missed that day like weaving string for a cat’s cradle, finger to finger to finger: the two stones. The set of red dust boot prints across the floorboards. The unseen ghost in the tangerine living room and the too-much-bourbon.

Like her father and her aunt, Sunshine has been raised on stories, and she can’t help but think in metaphors. Stories help her to bear loneliness and to make sense of her circumstances. For example, Sunshine and Billy dub the planks forming the entrance to their house the “Bridge to Terabithia.” The name, of course, refers to a book in which a boy and girl find solace and magic in a tucked-away private place; Sunshine and Billy similarly hide secrets in their story-filled abode. Here, Sunshine can convince herself that her dead grandmother is watching over her, and that by shopping, cleaning and cooking, she can prevent Billy’s storms. For his part, Billy can tell himself that his behavior is not out of line, and that lies are justified in order to maintain calm.

Though Billy received the gift of storytelling from his mother, from his father he inherited darker tendencies: depression, addiction, and a willingness to assault. Aunt Lou, meanwhile, leaves the house of her mother’s failed marriage only to land in one of her own. Catherine, Sunshine’s grandmother, was herself the product of a domineering father and a frightened, trapped mother. The characters seem doomed to live out their parents’ stories. Even geographically they circle like a hurricane around its eye: Catherine left Tennessee for Louisiana, and Lou left Louisiana for Tennessee only to end up, after her marriage failed, back in Louisiana.

In a story that Catherine recounts to her children, the yellow house on stilts where Sunshine and Billy now live came to rest on Only Road due to a bad storm. Using brooms as oars, Catherine navigated the house to land, while Billy employed a slingshot to kill an alligator that tried to make its home on the living room sofa. In a story told to Sunshine as truth, an alligator lives on one bank of the nearby lake, so Sunshine must promise never to swim beyond the yellow rope, lest she tempt the alligator.

The novel’s title derives from another story, shared piecemeal throughout the novel, about a greedy crocodile who eats everything in sight — boats, humans, jewels — until a girl with healing hands makes him a deal to save herself, and they become bound to each other.

The stories passed down are echoed by the narratives of the four generations depicted in this novel. Themes repeat: storms, trapped women, the dangers posed by moody and powerful men. As men turn violent, women and children become afraid, but they aren’t always able to flee. Not all stories provide escape.

Aunt Lou understands the burden of story. She resists telling Nash, her boyfriend, about her background. Instead she wishes for a map, so that she might convey her history less traumatically:

She could show and tell each painful part of her life, each meaningful smell and color and sight and sound, without ever having to crack open any part of herself in the process, without having to feel a single bit of the pain she was asking Nash to witness, without having to risk being swallowed by it.

The word “swallow” recalls the stories of alligators and crocodiles, and I suspect this is Pedersen’s intention.

What, then, of the heroine? The reader roots for Sunshine, a girl of plentiful imagination but few prospects. She is a victim of circumstance, born to a line of alcoholic and abusive men and to women who can’t manage to free themselves. Yet she loves Billy, who has redeeming qualities and who loves her in his way, even as he frightens her. Like Lou and Catherine, Sunshine recognizes the contradiction inherent in loving someone who treats her badly:

But if one thing loves us — a person or a crocodile — then we stay alive, and so the crocodile bride went on living in her little red house.

Pedersen’s novel — a rich layering of tales told, lived, and imagined — is a reminder of the power of story: to explain difficult truths, to illustrate possible outcomes, and even to offer a path toward a better life.

+++

+