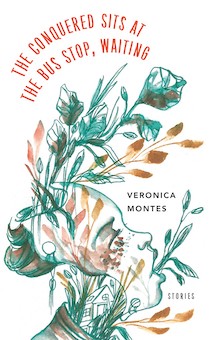

Black Lawrence Press, 2020

To be conquered is to be defeated, beaten, vanquished, crushed. The eight stories in Veronica Montes’ chapbook The Conquered Sits at the Bus Stop, Waiting are peopled by characters overwhelmed in some manner — by grief, by the desire to be seen, by the ceaseless march of time, by aging. But although Montes’ characters may be beaten down, they are not quite beaten yet. They cling to a teensy bit of hope, as suggested ever so slightly by the word waiting in the title.

An ethos of fierce smallness pervades the collection, making it distinctly appropriate for presentation in chapbook form. The diminutive chapbook has a powerful history of disseminating ideas to those who would otherwise lack the means to access them. The literary wares peddled by the “chapmen” of early modern Europe threatened those who held power while offering relief to those thirsty for knowledge. Powerful and accessible, the chapbook suits these stories of seemingly conquered women who nevertheless find their voices and their strengths.

Everything that threatens to conquer these characters is ubiquitous for readers as well. Nobody can escape aging, for instance, a theme that presents repeatedly. In “Lint Trap,” a mother imagines what she could create with the lint she routinely empties from the dryer’s filter. She cycles through family-focused ideas — dolls, tooth fairy pillows — until she finally hits upon knee pads and headbands for youth sports. As she imagines the celebrity she might earn from her “domestic ingenuity,” her thoughts darken. With grim humor, she reflects on how she might repurpose her collected lint to confront her aging body: “Could she prop herself against it to remain alert from three to five in the afternoon? Could she use it to plump the lines that have formed on either side of her mouth to refill her once magnificent breasts?” In the story’s last line, she wonders if she could use lint cushions “to muffle her screams, to plug her ears,” and whether they could buffer a “long and graceless fall.” Many people simply empty the dryer trap and move on, but Montes hits a nerve that will resonate with anyone trapped by mundane tasks, particularly those of motherhood. Yet despite the story’s gloomy end, it is clear that the narrator’s imagination will buoy her. With age comes knowledge and experience, and “Lint Trap” provides a reminder that these are complex moments. Astute wisdom and imagination are at play here, along with time.

Themes of motherhood and aging re-appear in “Ruby,” a story in which the title character, a teenage girl, flirts covertly (or so she thinks) with her boyfriend in front of her mother. The juxtaposition highlights the thrill of young love — one character remembers as the other experiences it. Ruby’s mother intuits, as mothers often do, that her daughter is up to something, though she doesn’t fully know what. In fact Ruby is up to something. In conversation with her boyfriend, she quietly emphasizes suggestive words in a kind of word play/foreplay until, unable to stand the sexual tension any longer, they bolt for his car under other pretenses, “puppy chasing puppy.” The mother says nothing. She is not surprised, after all, for she “remembers boys like this, the midnight phone calls, the musk of them.” The heat between the pair is well rendered, but the last moment of the piece poignantly frames that heat as another aspect of motherhood: the mother knows that there are some paths children must tread without their mothers. This journey of sexual awakening belongs to Ruby alone. When the lovers leave for the boyfriend’s car, Montes writes, “…and that is the last time that Ruby’s mother sees her because Ruby never comes back, not really. The girl who returns to the house is another creature altogether, blind and groping and fettered to an enormous, feral love.” The mother, no longer gripped by such love, “sees” her daughter, but her daughter, who returns from the experience “blind and groping,” sees nothing her mother sees, making their separation complete.

Many of Montes’ stories deal with separation. In “Ocean of Tears,” a woman struggles against overwhelming grief following her father’s death. A mermaid-like woman in a dream counsels her that she must “…cry an ocean’s worth of tears. Then you must cross the ocean in a boat of your making. When you reach the other side you’ll find a door. Open it, and this will be finished.” Even though the bereaved woman has already cried to the point that her eyes were “swollen shut,” she begins with difficulty to make the boat. A group of boys assists her, though she reminds them she must do it herself. After her journey across the water, she “arrived home at night, tunneled into bed, and cried until she fell asleep. It was like that for many years; it was like that forever.” When she finally reaches the door to which the mermaid-like woman directed her, she cannot open it, and she returns home without completing this final step. This ending reminds us that grievous loss is something one often does not, and perhaps cannot, get over. The narrator says, “It was easy to cry an ocean of tears, but building the boat proved difficult,” an honest recognition that staying afloat in the midst of grief is a challenge.

Although the narrator of “Ocean of Tears” waits for men to respond to her grief, none of the story’s male characters — an unhelpful optometrist and the boys who help her build the boat — bother to inquire about its source. A similar quiescence crops up in “The Sound of Her Voice,” a story about a woman with a husband whose face “disassembles itself” when he attempts to listen to her, “and the pieces do not slide back into their proper slots until she stops making sounds.” Blaming herself for this breakdown, the wife considers other ways to communicate. “Also — did you know this? — gestures are an effective way to speak with babies who don’t yet vocalize. She keeps this in mind for the future.” Like the inclusion of the hope-filled word waiting in the title of the book, here is a nod to the idea that perhaps the husband is the one who has yet to learn to fully communicate. This woman begins to understand that the breakdown is not wholly her fault. It takes two people to converse, after all.

Montes’ command of the text is subtle and gorgeous, a lyricism of emotional intention. Putting her new communication plan into practice one night in “The Sound of her Voice,” the narrator “places her cheek over her husband’s heart” in an attempt to send the signal for desire. She observes that the sound of “his heartbeat feels like a tiny punch, punch, punch against her face” which “makes her laugh (to herself).” The contrast between tenderness and violence is striking. Just as the reader expects this heartbeat punch to strike the narrator’s ear, Montes lands it against her narrator’s face, creating a wholly different emotional and visceral experience. Something similar happens in “The 38 Geary Express,” when a creepy bus rider sends a note to a young woman who is also on the bus: “I have been watching you do you notice do you like it.” The intentional lack of punctuation forces both the reader and the girl into an uncomfortable tension.

Emotionally nuanced, attentive to diction and laced with hope, Montes’ powerful stories are aptly suited for presentation in chapbook form and offer a clear-eyed view of the realities of everyday life.

+++

+