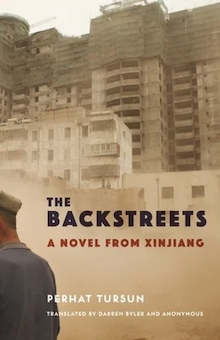

Translated by Darren Byler and Anonymous

Columbia University Press, 2022

How many ways can a human being disappear? Existentially: in the uncaring maw of an anonymizing city. Sensually: being completely disconnected from other humans. Noirishly: disappearing from sight. Physically: taken away, made not-human, by some vast and uncaring system.

All these possibilities are explored in Perhat Tursun’s novel from Xinjiang, The Backstreets. Tursun started writing The Backstreets in 1990, just as the modern history of the Chinese state and its vast Islamic western province began to collide. The novel is being published now, just as the Uyghur people are being ground to dust by the massive power of the state. Tursun’s culture is disappearing, person by person and all at once.

Translated by Darren Byler and a Uyghur writer who has remained anonymous for safety, Tursun’s novel takes place in the city of Ürümqi (spelled Ürümchi in the book). A regional capital built by colonial powers from the coastland in the 1700s, Ürümqi is the furthest city from any coast in the world. It’s remote. It’s enormous, compared to the relatively unpopulated countryside. And in Tursun’s novel, it’s a place of alienation and despair.

The story is told entirely from the disjointed point of view of a nameless narrator as he wanders the city’s streets looking for a place to spend the night. He is Uyghur in Ürümqi, near his village, which makes him an ethnic minority despised and distrusted by the Han majority. He is obsessed with numbers and searching for meaning. But meaning is impossible to find.

The narrator has obscurantist tendencies — he tries to reconcile strings of numbers to reveal prophecies, and he makes sure to leave all rooms with his right foot first. These might be superstitions, but they are also a way of establishing control, finding patterns, drawing in the meaningless.

He also repeats several sayings, none more than this one: “I don’t know anyone in this strange city, so it is impossible for me to be friends or enemies with anyone.”

That’s certainly half-correct, but as we see, being alone in a city built to colonize your people makes you everyone’s enemy.

The narrator is looking for a bed, trying to find an address in the anonymizing backstreets. He wanders through the “fog,” a choking winter pollution out of which emerge shapes of buildings and the forms of people. Tursun uses several arresting images for the lit-up windows in the fog: “the spit of a man whose teeth are bleeding”; “gloomy gashes on the body of a man who had been beaten to death”; “the eyes of a cat that had been aroused”; “the eyes of a dog looking at a bone in the hand of a person.” In this fog, monsters abound. Grotesqueries fade in and out, refusing to give directions. People seem huge and then tiny, distorted when they are not fading away. It’s not clear whether they’re unseeing or the narrator is just unseeable.

This surreality carries through the book, which has a physical cling, an itchy scent. Odors pervade the streets, repulsing the narrator even as he says that “a person’s imagination has a tendency to be strengthened by disgusting odors, pain, and hunger.”

Is he imagining things? Is he imagining latent violence in every encounter? Is he imagining the incomprehensible hatred directed toward him? It’s hard to say that he is, and he seems to understand that. He recalls stories from his father:

My father always told me these horrific stories. Like how someone broke his own kid’s leg after the kid let a sheep’s leg get broken while he was watching them. Or how someone stomped his kid’s head into the mud and abandoned him after the kid let a donkey cart get stuck in the mud. Somehow, these things seemed to belong not to the past but to the future.

Tursun’s narrator is right. Riots did overcome the city, and violence ravaged the Xinjiang homeland. Millions disappeared into concentration camps where the vast bureaucracy of a modern state mixes contemporary anti-terrorism talk with the odorific language of mutual brotherhood while using torture to establish ethnic nationalism. The events of the novel take place in 1990, but in the fog, the story transcends time as the narrator moves toward a horrifying present.

Tursun himself is among the disappeared, swept up into camps for no reason. His anonymous co-translator was also arrested, perhaps because of the translation, or for some other reason, or for no reason at all apart from the fact of their existence.

On the surface The Backstreets is largely apolitical. Although the disappearance of thousands of people is the tragedy of Xinjiang, the tragedy of one person remains the thrust of the story. But Tursun surely felt the mechanisms of vanishing around every corner and through every encounter, through bared fangs and rotten breath of sneering superiors. His narrator disappears alone within a choking, blinding city in which he is despised simply for being. At the same time, his vanishing is also the vanishing of many bodies, many souls. The narrator knows that the vast politics beyond his solitary life have a crushing physical weight. His fate points to a future of dimmed-out skyscrapers just out of sight of blinded and brutalized prisoners.

In a sorrowful passage that could sum up the book, the narrator reflects on his current neither here-nor-there existence within the terrible history of his oppressed and brutalized people: “The fog kept infiltrating my body and gave me a heavy, cold reverberation in my dark interior. My body was turning into mud. Water and earth were mixing together, but there was no sacred breath in me.”

+++

Perhat Tursun is a leading Uyghur writer, poet, and social critic from the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region. He has published many short stories and poems as well as three novels, including the controversial novel The Art of Suicide (1999), decried as anti-Islamic. In 2018, he was detained by the Chinese authorities and was reportedly given a sixteen-year prison sentence.

+

Darren Byler is assistant professor of international studies at Simon Fraser University and the author of Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City (2022). His anonymous co-translator, who disappeared in 2017, is presumed to be in the reeducation camp system in northwest China.

+

Brian O’Neill is an independent writer out of Chicago focusing on books, international politics, and the Great Lakes. He blogs infrequently at shootingirrelevance.com, and can be found tweeting on books, politics, and baseball @oneillofchicago.