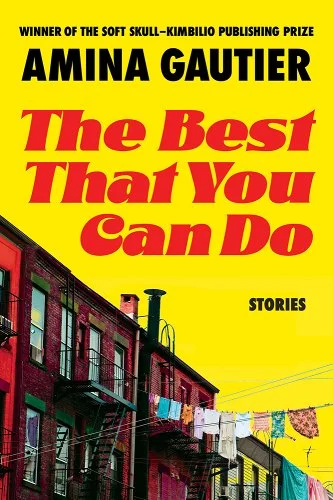

Soft Skull, 2024

The stories in Amina Gautier’s The Best That You Can Do, her fourth collection, pour forth in a headlong rush, with a rhythm as propulsive and natural as breathing. Gautier’s inhales and exhales can jump rope, or sit alone at a bar, or be held, clenched in fear, in an elevator full of white cops at a cop conference. The collection has a stiff breeze at its back, and it catches you bodily in its weather.

Fifty-eight very short stories, many just a page or two, operate in a kind of sketch realism. Taken together, Gautier’s gestural, suggestive, and symbolic impulses create a literary diaspora, as if the stories were a population, flung across pages, sharing origins, memories, and themes. If one story withholds traditional realization, another story, not so much linked as sistered to the first, fills in and fulfills it.

The Best That You Can Do is the arc of a life, from childhood to old age. The beginning wears its points of view, its “we’s” and its “you’s” in particular, lightly; childhood itself might be the narrator. Characters are mostly unnamed, recurring and capacious. They yearn to find a place, an identity, in contexts that repel them—Brownsville public housing, white people and white structures in general, an opaque Puerto Rico where a father vanishes. There’s an optimistic sense of working-it-out through memory, intelligence, and storytelling. A sixth-grade girl wins a scholarship to a prestigious private school that starts with summer “enrichment,” but “tuition costs more than your parents make in a year.” Will her neighborhood friends forget her? “Stop studying these kids,” her father warns. “They’re not going anywhere.” But the girl knows exactly where they’re going: “They’re scouring the streets for phone repairmen so they can cop telephone wire for double Dutch.” Gautier’s prose can move swiftly because she deeply knows this lonely girl, caught between cultures but with the gift of seeing herself bravely and clearly.

In a central stretch of very funny and often excoriating stories, an independent, successful, professional woman must contend with a cloying mansplainer, a lite misogynist—in other words, a much lesser male.

How can she guess that once she flies back to Chicago this man, sitting across from her so innocently buttering a roll, will inundate her with phone calls riddled with dull conversation? […] Calling every night without actually having anything to say, he talks to her as if they are an old married couple rather than two people who have been on only one date. He calls to tell her what he’s making for dinner. He calls to tell her that he’s fixing his fence. When she asks if there’s anything about her he’d like to know, he asks, ‘Do you wear high heels to work?’

“High heels” serves him up to us on a platter—I, for one, lift my little knife gleefully—but it’s that “innocently” that throws the scene into pathos. To add insult to injury, the woman’s sensitivity, autonomy, and success make her blameworthy, “high maintenance”: “Today’s black woman,” say her friends as they unfriend her, “wants too much.”

Romantic frustration and alienation give onto the section “Breathe,” presided over by George Floyd (Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor…without saying them, Gautier breathes many names), which takes on the routine, relentless antagonism and terrorization that Black people are somehow expected by white America to endure. Some of these stories twist toward dark humor, like “Tears on Tap,” which follows the wise, weary, beautiful, professional black woman to the “hottest, newest bar in town,” which serves “a pale pink drink with a one-inch head of foam”— white girl tears. “Certainly there was no shortage—every time a Becky got caught and called out for taking it upon herself to monitor and police a black body, she cried buckets—really, the owner could have gotten those tears from anywhere.”

The collection ends with an ingathering of moods, themes, and cares. The elegiac “Caretaking” makes a miniature novel. In a loose reversal of time within the larger arc, Mrs. McAllister, elderly and alone, with slurred speech and a frozen, alien body after a stroke, revisits the choice she made in her youth to honor a sister’s memory by caring for her family of origin rather than starting a new family with the man she loves. He loves her enough to let her go—and to return for her when it’s her turn to meet death. The final story, cast in the second person, serves to call all the you’s close, all the hearts cracked and cracked open—us. It’s not a spoiler to end with Gautier’s own words, which lift off the page and lodge in your opened heart: “You step over your body where it lies prone […] determined not to keep him waiting.”

+++

Amina Gauthier, Ph.D., is the author of three collections of short fiction: At-Risk (2020), Now We Will Be Happy (2014), and The Loss of All Lost Things (2016). Gautier is the recipient of the Blackwell Prize, the Chicago Public Library Foundation’s 21st Century Award, the International Latino Book Award,the Flannery O’Connor Award, and the Phillis Wheatley Award in Fiction. For her body of work, she has received the PEN/Malamud Award for Excellence in the Short Story. The Best That You Can Do won the inaugural Soft Skull-Kimbilio Publishing Prize.

+

Kirstin Allio is author of the novels Garner (2005) and Buddhism for Western Children (2018), and the story collections Clothed, Female Figure (2016) and Double-Check for Sleeping Children, which received the Catherine Doctorow Innovative Fiction prize from FC2 and is forthcoming in August.