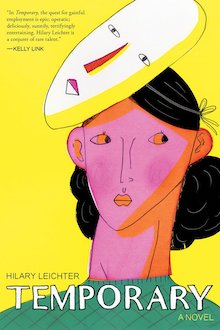

Coffee House Press, 2020

I read Hilary Leichter’s debut novel Temporary when I am twenty-one and looking for a job post-graduation. Indeed.com is my top searched website as well as my most-loathed enemy. When I type in keywords like “writing” and “social media” and “graphics” and “Chicago,” the ARC of Temporary winks at me. I glare back and ignore it in favor of applying for an entry-level job that requires five years of experience.

But Temporary is hard to ignore for long. The fabulist novel follows an unnamed, first person narrator as she navigates her way through a world where “there is nothing more personal than doing your job.” As a temp worker bouncing from job to job, her main goal — as was the goal of the first ever Temporary, created to give the gods a day off — is permanence, a concept that seems both illusive and nonexistence, since almost everyone she meets is filling in for someone else, too. The temp jobs range from almost believable (rearranging a closet full of shoes) to mostly absurd (opening and closing a set of doors every forty minutes) to strictly fantastical (filling in for a barnacle stuck to a rock). Accompanied by the ghost who lives in her necklace as a result of a past assignment and a collective of boyfriends, Leichter’s protagonist reads both as a deeply individual character and as a stand-in for twenty-something women struggling in the gig economy. As I edit cover letters between chapters, it feels like she specifically stands in for me.

Though it exists in settings of pirate ships and blimps, Temporary never becomes a madcap adventure story; an undercurrent of family and belonging grounds the novel in resonant, authentic emotion. Though temps are not expected to form lasting relationships the narrator resists this at every turn, forming close attachments to those she is impersonating and the people working around her. “And is this what it means to belong?” she asks herself, belowdecks of her temporary pirate ship.

It’s a question I’ve asked myself before, half-awake, on occasion, with my hands propped behind my head: Once after meeting a new friend. Again in the sweaty nook of my favorite boyfriend’s elbow, the discomfort of his sleeping position somehow only further proof of acceptance and inclusion.

Temporary searches for permanence everywhere: in jobs, in friendships, in romantic relationships, even in exile. It asks for it in obedience and subordination and in following the rules of capitalism. Finally, it asks for it in something else.

Despite its strikingly individual absurdism, Temporary manages to feel at home with books like Halle Butler’s The New Me and Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman as each follows young women struggling with personhood under capitalism. “She felt lucky to have coverage on her sick day,” narrates a bank robber whose bank-robbing duties are being filled by a temp,

and that word, coverage, was a word she liked — the shirt that covered her shoulders, the blanket that covered her body, the sleep hat that covered her head, the roof that covered her hat, the sky that covered her roof, the universe that always covered her ass, so lucky was she.

The postmodern world of Temporary means that anyone can be the bank robber for a day, and anyone can face the consequences of her actions. Belonging, to the narrator and her world, is filling in for someone else so well that she becomes them permanently — it doesn’t matter whether she becomes a murderer’s assistant or on a pirate ship or as a girl-on-the-street handing out pamphlets. Identity, along with job security, is constantly in flux.

These identity crises are coupled with the book’s lyrical prose. Leichter’s thoughtfully repetitive sentences reflect the idea, endorsed by capitalism, that capitalist systems can only be escaped momentarily through the freedom to make small decisions for yourself, often in relation to consumable beauty. “The job was in a lovely little house with a lovely little door,” Temporary’s protagonist remembers from her first job for which, as a child, she was required to open and close a set of doors every forty minutes. “The instructions were laminated and taped to the inside of a kitchen cupboard, which, being a cupboard and not strictly a door, I never had to open or close again if I didn’t choose to do so.” Later, in similar style, she imagines her boss engaging in ritualized self-care — waiting for newly manicured nails to dry — after firing an employee: “There’s a certain power in this voluntary immobility, Farren thinks, smiling. I don’t have to move if I don’t want to! My hands are as soft as my sheets! I take care of myself, she thinks.” The characters in Temporary are confined stylistically as well as literally, described in a circular pattern of thinking, obedience, and dreams of escape.

Though the fantastical settings and the mythical interruptions of the First Temporary may be too cutesy for some readers, prolific short-form writer and interviewer Hilary Leichter has a shining debut novel with Temporary. By taking a step back from real-world capitalism, her critique becomes even more effective. As I recognize myself within Temporary’s pages, I can’t help but wonder: what would I give up in exchange for permanence?

+++

+