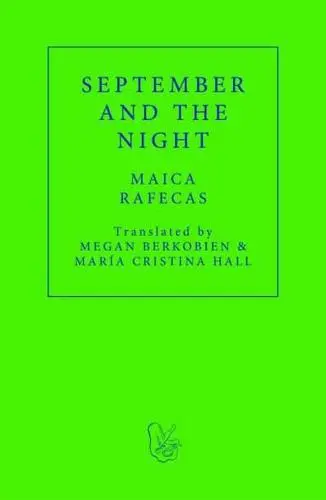

Fum d’Estampa Press, 2023

In coastal Catalonia’s wine country, families have owned vineyards for centuries. But the land was never completely devoted to grapes. Other crops have long provided sustenance and supplemented family incomes. As the monoculture that came with the twentieth century drove down profits, farmers took second jobs to support their vineyards. The death blow to the region—and the inciting action of September and the Night—is the government’s forcing families to sell their properties, which will be paved over to make way for a large Logistic Centre, a generic identifier for what ultimately means empty warehouses. While the Logistic Centre is an ever-present reminder of the threats that plague the area, the complication driving the novel is sexism of the culture, a force that runs so deep, it overrides the power of family.

For many, the sale of their land was fine. Maintaining a farm, working the vines, harvesting during the season, and fighting disease and climate change—all of these challenges were simply too much, at least for the men. This is certainly the case for the Llobeta Vineyard, owned by Magi since the death of his father, Grandpa Pau. And this is certainly true for his thirty-year-old son, a ne’er-do-well would-be poet named Jan. It is Magi’s daughter, Anaïs, who presents a problem.

Magi has neither the time, nor the interest, nor the commitment to tend to the grapes. What does he want? To go to work and come home without complications. The money from the sale will help.

Jan is unemployed and living with his father. He would like to return to a highly romanticized past, which means Samira, his longtime best friend and sometimes girlfriend. Otherwise, nothing is worth fighting for. Or, rather, it is too hard to fight for anything, even Samira. Samira, who grew up working with them in the vineyard, is off to Montreal on a fellowship to do graduate studies in anthropology.

The women are something else. Even Anaïs’ seven-year-old daughter has more strength than the men in the novel. But are they strong enough to combat the government’s takeover?

When Magi tells his children of the government’s plans, Anaïs commits herself to saving the vineyard. A forty-year-old mother recently separated from a husband who abused her, she owns a successful business, a design studio where she works on wine labels. Like the rest of her grandfather’s descendants, Anaïs sees the vineyard as something from the past. Unlike the men, however, she sees the present as a continuation. Her view embraces the land, the community, the history. Capitalism will destroy that.

One night, she slips from bed and out to the vineyard where she begins pruning the vines. Such is how her “little obsession” begins. She assumes care of the vineyard and takes up residence in a small building in it. In doing so, she begins to undermine the very foundations of her male-dominated world.

She has separated from her husband. But women don’t do that; after all, it was a good marriage. She has her own business designing labels for wine bottles, which she puts on hold while she takes over the care of the vineyard and the fight to keep it in the family. But women aren’t supposed to do that either; instead they are to care for their children. By working in the vineyard, much of the care of her daughter falls to her father and her brother. Her crimes mount. She collects bags of dog poop to spread in the vineyard. She collects the shards of pottery she finds between the vines. She catches glimpses of a mysterious old man in the vineyard.

Anaïs’s father reports her disruptive behaviors to the local authorities who, with bulldozers in the wings, have a psychological profile done on her. Her brother Jan supports his father, but only when it’s easy to. He meets Elisa, the social worker who was handed his sister’s case by the psychologist assigned to Anaïs, and repeats some of his sister’s “transgressions,” but he is busier objectifying Elisa than actually making his case. He complains about his sister in an email to Samira, rambling on about Anaïs’s “strange behavior,” how she must be “emotionally stunted,” abandoned by her mother and “orphaned by the land.” How else could she toss aside a husband?

He receives a 3,500-mile slap from Samira.

‘Stop with your bullshit! You should read over your texts before you hit send!’

‘What’s wrong? What did I say?’

‘Anaïs told you how sexist it was that you asked why she would ever leave a man who had “never abused her.” And you can’t take it. You’re trying to psychologize her.’

Samira tells him to get over his hang-ups and offers a means for doing so, in what amounts to a direct critique of all that Jan has lost. “You could start,” she tells him, “by paying attention to the land.”

His response reiterates the sexist underpinnings of the novel. But it also reveals that his romanticization of the past has nothing to do with the vineyard or the land other than as a means to a less complicated Samira. “Paying attention to the land?” he replies. “You’re crazy.” Later, as he sorts through his worries, he comes to a clearer articulation of the values his sister is challenging: “Family first, that’s right. There was a natural order to things: family before all else.”

The novel’s strength lies in its complexity. As Rafecas unwinds the motivations of her characters, she shows how their moral and cultural philosophies compete. In the series of contests that constitute the novel, there is little negotiation and even less compromise. Sadly, there are only winners and losers.

+++

Maica Rafecas (Llorenç del Penedès, 1987) is a social educator, anthropologist and publishing technician who has won numerous awards for her work. September and Night is her first novel.

+

Writers Megan Berkobien and María Cristina Hall frequently collaborate on translations from Catalan and Spanish.

+

Rick Henry has lived across the United States, but always returns to the sensibilities, landscapes, and histories of upstate New York. This is reflected in a number of novels and short stories including Lucy’s Eggs: Short Stories and a Novella (Syracuse UP), winner of the 2006 Adirondack Literary Award for Best Work of Fiction; Letters (1855) (Ra Press); and Colleen’s Count: Wednesday, August 16th, 1933 (Finishing Line Press). Find him at www.rickhenry.net.