Our editors share a few of the most memorable books they read in 2021.

Michelle Bailat-Jones, translations editor

In 2021, my reading life was ruled by three different kinds of hunger: first, a continuation of my post-pandemic appetite for comfort reading and old favorites; second, an intermittent but intense craving for books that tackled issues of climate and conflict with ingenuity, sharpness of vision, and a measure of grace; third, a yearning for books that explicitly and carefully worked to unearth beauty where it seemed least likely to exist. The books I loved this year were often unsettling in some way despite my desire for a tilt toward light rather than darkness. Here are the translations, mostly from 2021, that I feel did this difficult work, along with one favorite comfort read:

Wild Swims by Dorthe Nors (Graywolf Press, 2021), translated by Misha Hoekstra. Here are fourteen short stories that crisscross borders, both emotional and geographic, while exploring and inhabiting various threshold zones, either directly or by allusion. Often darkly comic and unsettling, Nors’s work is always intense, always intuitive, and rich with thought.

In Memory of Memory by Maria Stepanova (New Directions, 2021), translated by Sasha Dugdale, is a family history in the simplest sense, but the book isn’t simple at all. It’s very long, but a fascinating excavation, a book to take slowly. I was entranced by its leisurely meanderings through so many lives and locations and events. It’s a book that celebrates — quietly — the ordinary extraordinariness of human lives.

A Leap by Anna Enquist (The Toby Press, 2009), translated by Jeannette K. Ringold, is a virtuoso performance. Embodying a series of historical voices, Enquist sweeps through situations ranging from domestic tension to high war drama in a pure voice exercise that is much musical as it is technical. I can’t stop thinking about these stories and the minds she burns onto the page.

The title of The Death of a Beekeeper by Lars Gustafsson (New Directions, 1981), translated by Janet Swaffar and Guntram H. Weber, may sound grim, but there is no gentler book than this one. I’ve read this journey through the mind of a schoolteacher/beekeeper confronting his mortality several times, and it gives more on every re-read. I offer as proof the opening lines from the narrator: “Kind readers. Strange readers. We begin again. We never give up.”

+

Lacey Dunham, fiction editor

Mary Oliver, of course, requires no introduction. This year, straddling the so-called “normal” and the so-called “new normal,” I found myself drawn again and again to the outdoors, a place where I have often found solace. In Upstream (Penguin, 2016), a wide-ranging collection of new and old essays, Oliver, known for her poems that encompass the natural world, turns her keen observation to everything from the industrious spider in a rental house and an injured bird she brings home to rehabilitate to Whitman’s poetry and Poe’s female characters. To say her collection was an unexpected balm to my year might sound overblown, but as I read slowly, pleasurably, through her essays over the course of many months—often picking them up after returning from my own patch of woods and trails in my otherwise bustling urban city — I felt renewed.

+

Diane Josefowicz, book reviews editor

Veering between outrage and paralysis in the face of our ongoing national problem of accepting various political, social, and epidemiological realities, I spent the year searching for stories that put maximum pressure on narrative form in order to get a grip on particularly jolting changes of state, of identity and belonging, of who’s in and who’s out..

At its flinty heart, And the Bride Closed the Door by Ronit Matalon, translated by Jessica Cohen (New Vessel Press, 2019) is an experiment in the narrative possibilities of defiance. On the morning of her wedding, a bride locks herself in her room and refuses to come out. In her refusal, she acts like an explosives expert, deftly blasting open huge spaces into which two families, whose merger she is expected to effect, instead spin and drift. Despite her refusal to converse, Margie gives hints as to the sources of her discontent: a scrawled “sorry” on a sheet of paper posted at the window, a cryptic poem slipped beneath the door which, by remaining obstinately shut, becomes productive of a great deal — hilarity, grief, longing.

Saturation Project by Christine Hume (Solid Objects, 2021), the only book I gave to another writer this year, recasts the Greek myth of Atalanta in terms of the difference between productive anger and mind-obliterating rage. Left for dead as a newborn and rescued by a bear that has lost her own cubs, Atalanta is finally raised by the same hunters who killed the cubs in the first place. Atalanta not only survives many dangers but also, and more importantly, endures being changed by them. Refracting the myth through elements of essay and memoir, Hume suggests an oscillation between the deliberate use of strength and an outright ferocity that eliminates thinking entirely. Breaching this boundary results in a catastrophic loss of individuality, of one’s own internal hum. A final section, on “wind,” is about more or less violent disruptions that arrive from without — a tornado of fake news, say, or an airborne plague.

The title of Prosopagnosia by Sònia Hernández, translated by Samuel Rutter (Scribe, 2021) technically refers to a difficulty recognizing faces. But it is also the name of a game confected by the teenaged girl at the center of this short novel, who discovers that she can hold her breath until no longer able to recognize herself in the mirror. One day, she tries this trick while looking at a painting and faints. Sent home from school, she soon finds herself within the painter’s personal orbit, alongside with her unhappily status-seeking mother, an aspiring journalist and celebrity hanger-on whom the daughter both despises and, of course, resembles. As mother and daughter negotiate their present situation and their future possibilities, they are drawn more deeply into the strange and occasionally brutal world of the painter, who is not exactly who he appears to be, either.

Shatila Stories (Peirene, 2018), edited by Meike Ziervogel and translated by Nashwa Gowanlock, is a remarkable novel-in-stories about Syrian refugees living in the Shatila camp in Beirut. Over the course of a three-day workshop and months of subsequent collaboration, Ziervogel worked with nine refugee writers — ranging in age from eighteen to forty-two, and all living at Shatila — to weave their stories into a complex but unified narrative. The fact of this book’s existence seems like a miracle on its own. Violence, disease, and death are omnipresent in the camp, deepening the trauma of displacement; in the workshop classroom, there are no computers or even fans, and a dance class proceeds noisily the other side of a thin dividing wall. Still, the participants write, revise, and write some more. The result is an astonishing statement of ferocious resilience: “Spare us your good intentions, your quiet pity. Instead, look up and raise your fist at the sky.”

+

Steve Himmer, editor

In 2021 I had a hard time with high-stakes plots. Anything I picked up to read that set in motion grand circumstances and definitive causality and characters taking bold, decisive action on a big dramatic canvas was likely put down after very few pages (or turned off after very few minutes). I suspect it was a result of my constrained pandemic lifestyle and the generally overwhelming state of the world — the exhausting pace of the news cycle, and the constant escalation of irrelevant disagreements and inarticulate tweets to scorched-earth combat. Fiction and nonfiction alike that promised to know how the world works felt unconvincing and almost insulting. The “escape” I wanted wasn’t imagining a fantasy world but imagining the world in which I thought I was living not long ago, a world with space and time to stop and make sense of where you are before everything changes again. I was drawn instead to tightly-focused idiosyncratic experiences, often grounded in place and in the experience of one character or writer looking closely at their own particular world, and trying to remain themself in that world despite buffeting forces beyond their control. So here are a few books that drew me away from the noise for a while, books that felt more like a slow, attentive walk than a breakneck dash to destruction.

Brood by Jackie Polzin (Doubleday, 2021), with its willingness to be small to explore bigger things, found me early in the year when I needed to read it. It felt quietly radical in declaring that this much — a few backyard chickens, a marriage, some significant but not action-packed choices — is enough to make art at a time when (it seems to me) we’re pushed from many sides toward louder, more declarative, more comprehensive “aboutness.” The novel’s tight focus and insistence on everyday tangible immediacy let the narrator and at least this reader simultaneously avoid and engage the heavy things in life and death that weigh on us all.

Vloed by Lucia Dove (Dunlin Press, 2021) is a deft, subtle demonstration of the possibilities of hybrid form. Exploring the shared experience and legacy of a 1953 flood impacting both the Netherlands and the UK, Dove’s combinations of poetry and prose, personal and historical, and visual and textual offer not only a rich sense of that event and its lingering presence — and its echoes through her own transnational life between the two countries impacted — but also an awareness of their ultimate unknowability. Instead of making claims to definitive understanding Vloed becomes as curious and compelling a liminal space as the land bridge that once connected the water-separated nations it ties together.

One of my constant frustrations as a reader and viewer is the lack of stories about people spending time outdoors not because they’re trapped and pursued, or finding dead bodies and seeking the killers, or being attacked by the natural world in some way. I want to see characters going outdoors because they like being there, not as a threat but as a setting for all the complexities of human and inhuman lives. The Paper Lantern by Will Burns (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2021) gave me that more than anything else I read this year. Its narrator, his already constrained life stalled completely by the lockdown of COVID when it closes the English pub operated by his family, walks his local landscape with all its layers of history, ecology, politics, culture, and memory, and for me that was much more like being in the world as I know it and want to explore it than more forceful fictions of murderous, menacing wilderness could ever be.

Subdivision by J. Robert Lennon (Graywolf Press, 2021) does things that if someone told me they were going to happen I’d be suspicious because they would sound like impossible and frustrating twists. But this novel sticks the landing and then some. As its unnamed narrator tries to find her way in a strange new city, encountering increasingly mysterious people and events (and a birthday party that has become one of my favorite fictional scenes), the slow build up of both understanding and risk — and the skill with which Lennon manages that — gives emotional weight to things that I wouldn’t have expected to become so moving and emotionally complex. It surprised me in the best ways and is a novel I know I’ll read again both to enjoy and to learn from (I hope!) as a writer.

Temporary by Hilary Leichter (Coffee House Press, 2020) was so good — and so delightful! — at confounding my efforts at interpretation. It demanded to be taken literally, allegorically, poetically, mystically, politically and otherwise one after another like a worker expected to adapt themself to new situations over and over. Which happens to be what the novels about as its eponymous temp bounces or is bounced from job to unlikely job in a system that put her ability to remain herself — or any self — at constant risk. That unsettled, unsettling quality created a resonant, lively experience because even though I could never put my finger on quite what to make of the novel I never stopped wanting to try or to engage with the cascading absurdity and strange familiarity of its events. The more unlikely the fortunes and misfortunes of the protagonist became the more it felt to me like the ordinary state of being alive and I was grateful for it.

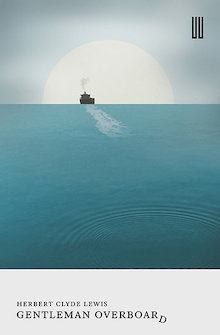

Finally, and this one just snuck in under my reading wire, Gentleman Overboard by Herbert Clyde Lewis (Boiler House Press, 2021) is the first title in a new series of rediscovered books and an auspicious launch to that line. The story is simple: a wealthy, successful man falls from a ship and is left behind treading water in the Pacific, waiting for rescue. Lewis’ balance of tight, sensory focus on the experience of those hours adrift and the thoughts of the protagonist, along with restrained awareness of what’s happening elsewhere, give remarkable pathos to a character who might become a cliché of privilege in other hands. It’s a novel deserving of this rediscovery but it shouldn’t have disappeared in the first place, and the tragedy of Lewis’ own erasure from cultural life by the Hollywood blacklist gives the novel another layer of resonance in our own fraught moment.

+++