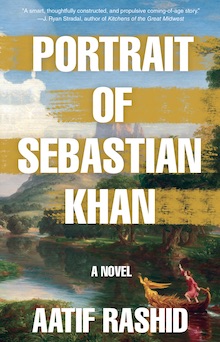

7.13 Books, 2019

One of the most striking qualities of Aatif Rashid’s debut novel, Portrait of Sebastian Khan, is its ability to lay bare misunderstanding, in the moment it appears. This is not just about confusion, although many characters experience bewilderment throughout the narrative, but about willful misunderstanding or misinterpretation. Rashid tips the reader off clearly about the significance of this feeling from the prologue, when we meet Sebastian, gazing at a painting and reading his own feelings into it. Sebastian studies art history — to his father’s dismay — at UC Berkeley, which serves as both setting and timeframe to the narrative. Early on, Sebastian eagerly joins the Model UN team, not so much due to his interest in learning about global issues, but more because of the artifice. He “like[s] it precisely because it’s fake. …It’s all of the glamor of international diplomacy without any of the responsibility.”

It makes sense that MUN is the backdrop for this startling coming of age story. Sebastian, who enjoys it specifically because it is playing at something he isn’t — and has no desire to be, unlike many of his teammates — spends much of the novel leading his girlfriend Fatima along a path she misunderstands because he wills her to. He is the somewhat-doting, mostly-appreciative boyfriend in Berkeley, but when traveling for conferences, cheats on her with an increasing (and alarming) lack of concern and empathy. Initially this is just when he crosses that line of locale, but as he sinks into desperation about the impending doom of graduation, he continues his affairs at home. At this point even those around him, who sort of smiled benignly at his prior indiscretions, cannot condone what began as inconsiderate and has become outright cruel. Fatima sees them as moving in together, getting engaged. There is something like love in Sebastian’s feelings for her, but not what she perceives and not the feeling he chases.

Sebastian is a delicious protagonist (something I’m sure he would love to hear). Often a jerk, often pretentious or smug, always quick-thinking and very intelligent — if persuaded of his own beliefs — it is easy to enjoy judging him. It is also easy to feel for him. His anxiety about leaving the safe bubble of Berkeley rings true to anyone who has ever struggled with liminal spaces in life. His friends find it ridiculous that he is so preoccupied with a local homeless man and doomsday believer, who neatly composes a sign on his whiteboard every day, counting down until THE END, but to Sebastian, who perhaps rightly senses that his freedom to be irresponsible whilst claiming independence is ending, he is a telling figure.

Part of Sebastian’s fear that he is losing his freedom is also tied to Fatima, who is much more deliberate creature than he. Highly driven and invested in her future, Fatima hopes to go into tech and quickly settle into a comfortable, stable life with — from Sebastian’s perspective — little to no adventure. Despite coming from the same faith, Fatima is religious and Sebastian really only taps into his faith when he embodies it as a character in Model UN. Fatima abstains from many of Sebastian’s favorite things, chief among them alcohol, sex, and general debauchery. These major differences in their preferred activities, which should indicate to both of them the mismatch between them, simply serves to enable their mostly separate lives.

The people Sebastian surrounds himself with challenge and support him in troubling ways. While he positions Fatima as his partner, the most important person in his life is truly Viola, his devil-may-care, brilliant and lewd best friend, who is constantly manifesting new flasks of alcohol and pushing him towards women to fuck. Imogen, a tightly-wound and highly ambitious (but lesser-valued) member of the Model UN team, is constantly at his throat about how he doesn’t care enough, how everything is a joke to him. Nonetheless, in spite of figures like Fatima and Imogen — with whom he ultimately develops a sexual relationship — Sebastian is used to getting his way with women.

One who really knocks him back is Helena, a fellow art historian who has her whole career (museum curator) planned out. A “modernist, through and through,” she enchants Sebastian after listening to him interpret Beata Beatrix, a Pre-Raphaelite painting — his favorites and his specialty. “I’ll admit, it is quite beautiful,” she says, and Sebastian imagines her less as a human, but as a comforting beacon of feminine warmth. Looking for her, later, in a club, he reflects on other students dancing sexually:

Before, if he were searching for [past lovers], such unbridled sexuality would have fueled his roving eyes, [but] he now finds this open display of lust distasteful, a reminder of the basest level of desire from which he knows Helena is separate. She isn’t just a body…craving carnal pleasure. She doesn’t sweat. She glides down museum halls and speaks in calm, comforting tones about art. She glows with divine light.

While he decides that Helena isn’t just a body, his separating her from humanity that sweats serves to dehumanize her just as much. Instead of making her a sexual object, as he usually does, he makes her almost holy, otherworldly. So when she humiliates him in front of other delegates, his new fantasy of purity is destroyed by human cruelty. “What’s wrong with the Pre-Raphaelites?” he asks, hurt by a comment she makes. “You mean besides the fact that their entire movement is just one big male-gaze circle-jerk?” she responds. And just as quickly as he became enamored of her, “in a flash, her divine light disappears.”

One of the most intimate moments Sebastian experiences is with Fatima, visiting his mother’s grave on the anniversary of her death. “Do you think I’d be a better person?” he asks her, “If she were still alive?” Fatima assures him of his goodness, but the closeness of the moment is ruined soon after, and Sebastian plummets away, looking for validation that his vices are desirable. Asking such a question of virtually any other character is unthinkable — perhaps Viola, but not in earnest. Something about the cemetery, a liminal space on the threshold of death, stirs this in him. Death, THE END, and the uncertainty of the future all hover over the pair in this moment. Fatima’s certainty in Sebastian is so strong, but her confidence in his goodness, her willingness to rewrite the narrative of who he is, cleaves them from each other. Her certainty can’t be comforting because Sebastian knows and embraces it to be untrue. Almost as if to prove it to himself, he proceeds with an affair so recklessly that Fatima quite literally walks in on it.

While Sebastian’s time at Berkeley ends, and with it, virtually all of his meaningful relationships, his fear of THE END of life as he knows it is abated, and the novel ends on a cautiously hopeful note, one sown from humility and Sebastian’s first desire to take on “real adult” responsibility and experiences. Showing real growth over his time in college, the last few pages return Sebastian to the painting he first saw years before, in the scene in which Rashid introduces us to Sebastian as a mis-interpreter. Seeing it, Thomas Couture’s The Thorny Path (1873), with a new mindset, Sebastian is chilled, but also inspired. One gets the sense that he hasn’t completely actualized or understood the full range of his experiences, but perhaps that is the best place to be after the comfort of college, on the precipice of the next chapter of life: ready to grow, to seek progress, to look for truth.

+++

+