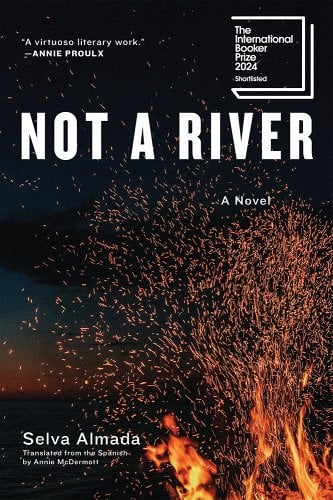

Charco Press, 2024

Set mainly on an island in the Paraná Delta, Selva Almada’s Not a River, the final entry in a loosely connected trilogy, tells the story of a fishing trip gone wrong. On the trip are three men coping badly with a shared tragedy. Their trip repeats one from twenty years earlier, except old friends El Negro and Enero are no longer joined by their third musketeer, Eusebio; he died on the island, and now his son Tilo stands in as substitute.

Like the island, Eusebio’s absence is a tangible presence throughout; without him, all three men feel like “a part of [them], real and concrete had to die as well.” This is literally the case for Enero, who loses a finger soon after Eusebio’s passing. For those left behind, his absence constitutes a dissipation that extends well beyond metaphors of loss.

The tragedies in Not a River are often met with denial. Unable to come to terms with Eusebio’s death, Enero flirts with girls and shirks his problems, often wearing the expression of “a little kid who’s screwed up.” Watching Tile, he falls prey to illusion, wanting to repeat the past and hoping to catch a glimpse of Tilo that will allow him to feel that Eusebio is still around:

If he didn’t know it was Tilo he’d say Eusebio had come back. If he couldn’t see his own bulging belly, his pudgy hands, his stump, his greying chest hair, he’d say Tilo was Eusebio, who hadn’t yet died. That the three of them were fishing again, just like back in the day.

A literal child at the time of his father’s death, Tilo’s grief is painfully acute. At Eusebio’s funeral, Tilo lays under the casket wondering whether his father is actually inside, wanting to believe he has only disappeared. Later, Tilo joins his cousins as they laugh and kick dirt onto the coffin.

Sharing the spotlight with these characters is Siomara, a local of the island. While she is only tenuously connected to the main characters—her brother and daughters bump into them—she is in the depths of misery. Her trauma—which no one, including Siomara herself, is eager to confront—reignites a childhood obsession with fire. The house she shares with her daughters is slowly being stripped of its furniture; starting fires is a way of “getting rid of her anger, pushing it out of her chest.” Sometimes the urge is so strong she resorts to burning whatever is at hand. El Negro, Enero and Tilo spend their time fishing, while Siomara works methodically: burning furniture, cooking, throwing food away when her daughters don’t come home.

The long repetitive days chronicled in Not a River paint a picture of worlds rocked by grief. The present is reduced to little more than a vehicle shuttling between a lost past and the next world. Almada’s shifts in time are so seamless they can be hard to discern. Her dialogue, in contrast, is fragmented:

Right.

She said.

You wait here.

She said.

And you come with me.

She said.

The girl followed her, miserable and ashamed.

Foregoing all punctuation in regards to direct speech, the dialogue is akin to poetry, prompting the reader to linger on almost every line. The result is a tension that stretches across the whole book, and the violence that bookends the story is almost to be expected, though it is no less effective because of that.

A painful portrayal of how grief ruins people, Not a River is is a book of disappointments, cruelty, and despair. As this economical novella drifts seamlessly between past, present, and the afterlife, it’s not always clear where the spotlight is hovering; the forks in this river can be hard to sense. But as Almada battles all of this sadness, she guides the reader through. Her clear and penetrating understanding of misery renders this difficult story a comfort.

+++

Compared to Carson McCullers, William Faulkner, and Flannery O’Connor, Selva Almada is considered one of the most powerful voices of contemporary Argentinian and Latin American literature, and one of the most influential feminist intellectuals of the region.

+

Annie McDermott’s translations include Mario Levrero’s Empty Words and The Luminous Novel, Feebleminded by Ariana Harwicz (co-translated with Carolina Orloff) and City of Ulysses by Teolinda Gersão (co-translated with Jethro Soutar). She has lived in Mexico City and São Paulo, Brazil, and is now based in London.

+

Colm McKenna is a bookseller based in Berlin, Germany.