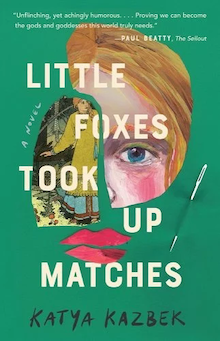

Tin House Books, 2022

Little Foxes Took Up Matches is set in Russia, and I am reviewing this liberatingly slippery novel just as war has spilled out from that country. Katya Kazbek, whose heritage is Russian, Ukrainian, Greek, and Jewish, and who writes in both Russian and English, might be the perfect indefinable author for such strange binary times, and her book comes at just the right moment.

Around the world, people are witnessing the slaughter of Ukrainians to satisfy a mad ambition, and they are rallying to the cause of Ukraine. But expressions of anger toward Russia are taking weird forms. There are gestures of meaningful solidarity, of pointless anger, of xenophobia, of group ideology, of staking identity. Tchaikovsky, who survived the Cold War, is absurdly being shelved; Russian vodkas (and even some non-Russian ones) are being dumped. What all of these movements, from tanks pouring into Ukraine to vodka pouring into sinks, have in common is that they are about binaries. Either Russia deserves Ukraine, or Russia deserves nothing. Either history is destiny, or it means nothing at all.

Into these binaries, these either-ors, comes Kazbek’s novel, a shattering memory-soaked look at poverty-stricken, ash-gray Russia during the horrible dissolution of the 1990s. It’s also a stunningly heartfelt story of a boy, Mitya, who dresses as a girl and has no idea if he is male or female, gay or straight, a wanderer or a homebody, or nothing. Or everything.

Mitya, who as a baby swallowed a needle and has carried within himself the idea of a sudden lancing death, is a child when the Soviet Union falls and a briefly-heroic Boris Yeltsin clambers onto a tank, stopping a coup and arguably setting the twenty-first century into motion. But first came the 1990s, when Mitya’s family lurches slowly from comfort to poverty, from employment to uncertainty, and from some peace to a measure of chaos.

For Mitya, this historical unmooring parallels an equally cataclysmic personal transformation. Kazbek sketches Mitya’s awareness of his sex, the strange dangly parts that a girl classmate doesn’t have, and his curious indifference to their meaning. He puts on makeup. He dresses as a girl whom he calls Devchonka, capitalizing the diminutive for “girl,” which his father, a veteran of Afghanistan, calls him insultingly. Mitya’s father is coldly dismissive of his child — though, of course, he is also widely disappointed with his own life and inability to find work, as a veteran whose nation no longer exists. Worse still is Vovka, a cousin who is a veteran of the Chechen war who, brutalized by that vicious conflict, in turn brutalizes others.

Although Mitya is timid, he is also brave. He tries to solve the murder of a homeless man who accepted him. He falls in with street toughs and mob-adjacent underground vagabonds, one of whom seems to be the first real homosexual Mitya knows. He goes to rock concerts. Most touchingly, he falls into friendship with an older girl, Marina, from Ukraine. She tries to help him navigate the police, the worlds of grown-ups and family. She herself is in Moscow looking for money, for love, for freedom from the stifling poverty and go-nowhere backwardness of Donetsk. That she’s from this flashpoint region and can move easily between the new borders is not lost on the reader.

Marina, kind and brave, searching and lost, careless and thoughtful, has no idea where her life is going. She is one of the most deeply sympathetic characters I’ve read in a long time, a true human being working through a time when being a human was a weakness. She has no real shell, and the reader is always terrified for her.

Kazbek weaves Mitya’s story with one of Russia’s founding myths, the fable of Koschei the Deathless, a malevolent figure. The Koschei is also a swallower of needles in some tales — swallowing a needle that winds up inside animals layered inside other animals like nesting dolls. But Kazbek’s Koschei veers away from traditional fables. This Koschei leaves the story and creates its own, fluidly moving between genders even as the great mythmakers try to box it in. What seems like an allegory seems more and more like Mitya’s own version of history.

That’s one of the lessons of the book: When faced with choices, when looking at forms, when a parade of ashen census demons force you to decide who you are based on what they want you to be, you can do something more powerful than saying no. You can shrug your shoulders and invent something new.

Kazbek spoke beautifully of this in a recent tweet about that shrug:

When you come from a much-suffering people — like my Greeks, Russians, Ukrainians, and Jews — when your gender, or lack thereof, and queerness, and rejection of xenophobia are a target on your back your whole life, you arm yourself with powerful tools: writing, magic, imagination.

The title of the book speaks to this position directly. At a concert, Mitya hears a confusing pastiche of lyrics: “Little foxes took up matches / and set the azure sea ablaze / it’s us the control point dispatches / To settle the impending craze.” Although Mitya knows the first two lines from a familiar children’s poem about rebellious animals, the rest seems promisingly original:

This mix of the old and the new struck Mitya. He didn’t understand exactly what was implied by the lyrics. But it all still made perfect sense to him, because he saw the power of words put together this way. It was similar to what he felt when he became Devchonka…. It was the feeling of truth and beauty conveyed through art, and Mitya realized he wanted nothing else in the world but to keep recreating this feeling.

That’s liberating. That’s exciting. The book is filled with these moments, heightened by their contrast with the realities of endemic corruption, police brutality, and soldiers wrecked by pointless wars. These realities make the need for beauty starkly clear.

In what might be the book’s most intimate and painful scene, Mitya observes his violent, sexually-abusive cousin, asleep during a brief period of trying to reform:

Vovka was sleeping there quietly, and because in the rush no one had closed the curtains, Mitya could see the lamplight from outside on his cheek. Vovka’s eyelashes were lit up by the yellowish glimmer. He looked young, innocent, just a boy, and Mitya felt sorrow in his chest. If only there was nothing that had come before, and this is all there ever was.

The heart breaks at so much wasted life. But things always come before. We can’t help the times we live in, or the nation to which we’re born; we can only find a way to navigate, to be ourselves in those times and to reject the simple choices we’re offered. Kazbek reminds us that there’s magic when either turns to neither; freedom rejects the or.

+++

+