Mason Jar Press, 2021

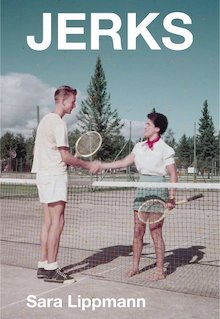

Sara Lippmann’s Jerks is a book you can indeed judge by its cover. While the retro photo of two tennis players shaking hands is comical and fun, an undeniably rich story is packed into the image, which hints at hidden depths. Are these seemingly civil people as nice as they appear? The image neatly sums up Lippmann’s collection: It’s funny, but beneath the crackle of her electric prose is an entire macrocosm.

The goal of all short fiction, of course, is effective compression. Lippman’s mastery of this art is apparent from page one. The collection opens with “Wolf or Deer,” about a fourteen-year-old girl at summer camp as her parents separate and she develops an interest in a twenty-something gardener. The language is concise yet so vividly descriptive that it evokes nostalgia, even for those of us who never attended camp: “We were 14: bad skin and braces and too much hair. Hand job lessons with the shaft of a curling iron. We licked juice powder raw, stained tongues a cherry red.” The story sets the tone for what’s to come: stories that are somehow simultaneously heartbreaking and hilarious.

In the next story, a group of tennis moms uses the reality show Polyamory: Married and Dating as a vehicle (or shield) for sharing their own sexual fantasies, including the narrator’s attraction to her daughter’s tennis teacher. The juxtaposition of these two stories — a young girl’s yearning for an older guy followed by a middle-aged woman’s desire for a younger man — is intentional and effective. With these two tales of longing Lippmann paints visceral portraits of desire, how we often want what we cannot have.

These first two stories set a pattern. Juxtaposing tales of adolescence and adulthood, Lippmann weaves a tension between youth and aging. The younger narrators want what’s up ahead. The adults, if not exactly wistful for youth, seek to quell the restlessness that accompanies being settled; many of Lippmann’s adult female narrators feel stuck in domestic life and yearn for more. As the narrator of “No Time for Losers” says: “My body is no longer young but it is a body that has served me, as much as a body can, as a repository for memory. It is a body whose want knows no limit.”

A few stories consider what it means to survive. In the title story, a Brooklyn-based couple makes beef jerky for holiday gifts. While the narrator contemplates the futility of everything and her husband is drawn to self-sufficiency, their six-year-old is budding breasts from “who knows what’s out there.” It’s one of several stories that creates friction between our daily grind and threats to our very existence, like climate change.

One of the most cutting stories is “Neighbors.” In one long breathless paragraph in the second person, Lippmann examines how our pasts intersect with our current struggles, and how where we live can merge the two. Lippmann crams so much into this three-page paragraph: despair, despondency, resentment, and, of course, her trademark wit. She writes:

You buy the crappiest off-brand aluminum foil because you don’t wish to outlive it. The glint of Freddy Krueger’s hands once sent you running from sleepovers. Children tossed your lovey in the oven. This is your horror story. Violence is everywhere. The neighborhood has changed, no judgment, only of course there is. Why should anything stay the same? Check out the hair and shoes on the actor across the street who gets drunk on his porch and watches you. Some people are home. You’ve been home for years. Thank God for squirrels.

This story is a good example of another thread running through this collection: the battle between the mundane and our desire for something extraordinary, anything outside of our usual humdrum lives. Lippmann shines light on the humor in that fight, how even an unexpected fortune can sting and how sometimes, the only thing we can do is laugh.

There’s much to admire in these eighteen stories: the electric witty prose, the character depth achieved in mere pages, the way Lippmann tells expansive stories in such condensed form. In the heart and relatability of each story, we recognize our own fumbling desperations. Like the cover image, these stories full of humor reveal how our desires can sometimes bring out the worst in us — how maybe, under the surface, we’re a bunch of jerks.

+++

Sara Lippmann is the author of the story collection Doll Palace (Dock Street Press). She was awarded an artist’s fellowship in fiction from New York Foundation for the Arts, and her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Millions, Fourth Genre, Slice Magazine, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Diagram, Squalorly and elsewhere. Raised outside of Philadelphia, she teaches in Brooklyn where she lives with her family and co-hosts the Sunday Salon NYC.

+

Rachel León serves as Reviews Editor for West Trade Review and Fiction Editor for Arcturus. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Fiction Writers Review, The Rupture, Entropy, Split Lip Magazine, and elsewhere.