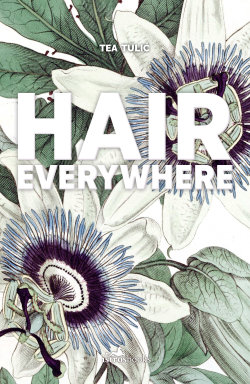

Istros Books, 2017

The book begins in childhood, as a guileless girl runs out the door with her pocket money, passing a slouched, drunk neighbor on the stairs. When she returns, the man is surrounded by figures in white coats, a blood-soaked hat sits abandoned next to his lifeless body, and his “chance for a new day” is wasted. Tea Tulić’s debut novel, Hair Everywhere, is a manifestation of our growing obsession with autofiction, setting down a deeply personal experience of bereavement. In a laconic, first person present tense, it tells the delicate and painful story of an unnamed narrator reconciling her mother’s lost battle with cancer.

The novel is written in fragments that rarely exceed a page in length. Like an intermittent sleep on a long train journey, you catch glimpses of passing landscapes, dreams and memories occur simultaneously, and you can’t quite recall where you’re headed. Published in Croatian in 2011, the book has a renewed life in Coral Petkovich’s shrewd and sensitive translation.

The narrative focuses on three generations of women—a mother succumbing to disease, a young protagonist coming of age, and a grandmother coming to terms with the death of her child. Tulić offers readers a privileged view into a matriarchal oikos, in which male characters exist only peripherally—including the father, whose defining feature is best summarized in the phrase: “Dad kept quiet about all this.” The women, however, inherit each other’s possessions and fears; their intimacy and indebtedness gradually mature into a relationship of mutual care.

The changing relationship between generations is best demonstrated in the series of threadbare conversations which occur between the adolescent protagonist and Grandma—two women at opposite ends of life, united by a common devotion to their daughter/mother:

“God won’t take me.”

“He would, but you won’t let him.”

“I don’t want to be a burden to anyone.”

“You’re still here for a reason.”

“To help the family.”

“Then, please, get up from the bed by yourself!”

When the narrator asks, “what is it that makes me you?” and adds, bitterly, “because I don’t want to inherit your feelings,” it is because she knows that it is already too late. The three generations of women are incarnations of each other—as Grandma loses her family members one by one, she laments, “I’ve been left all alone.” When the protagonist buries her mother, she sits down on the bed and thinks the same: “I’ve been left all alone.”

The philosophy of the cancer cell is infinite growth, but Tulić’s prose is an exercise in moderation, making it the perfect antidote. The lack of pedantic signposting allows the reader to slip into the role of I with ease as the chapters oscillate between birth and death, innocence and adulthood, past and future. While cigarettes, superstition, and the titular hair recur as serial motifs, death outdoes them all over the course of some 129 vignettes:

One day, Mum gave me money to buy tempera paints for school. I bought a hamster. I put him in an empty glass aquarium and watched him gather up carrots and green lettuce and carry them into the corner. When he finished his work, he climbed up over the stacked vegetables and ran across the carpet. Mum screamed:

“A mouse!”

“It’s an ornamental mouse,” I said.

We gave the ornamental mouse away after that, to a girl who had another such ornamental mouse. One morning, that one swallowed him.

An entire menagerie of childhood pets—hamsters, turtles, budgerigars, and dogs—die or disappear as the protagonist free-associates on her mother’s impending passing. Tulić treats death baldly, at times with a child’s tentative voice, and in a manner that reinforces it as a natural part of life, rather than force to be contested.

As her mother’s condition deteriorates, the protagonist becomes increasingly pensive and the chapters alternate feverishly between caring for her mother and her own development, which includes everything from giving up God for Murakami and Houellebecq, to a sudden distaste for the unkept people in the town market. Picking up a self-help book, she wrestles with a new imperative: Think about nice things. “And I think about nice things,” she states, “I buy myself a nice dress, I like myself in it, take it off, lie down on the bed and blame myself for buying it in these fucked up times.” Despite her regret, the book succeeds in doing just that—thinking about nice things, whether as a form of resistance or as a way of surviving.

The novel reads more like a stream of associative memories, duly chewed and contemplated, than a coherent narrative. While the progression loosely follows that of her mother’s illness—diagnosis, treatment, hope, loss—the protagonist’s unbridled train of thought ensures a sundry and surprising collection of ruminations. In that sense, it captures the nature of life and loss, in which loss is always tempered by the feeling of the sun on one’s face, or by the prospect of people—of children—which one has yet to meet:

These children carry beautiful names. And they laugh even when they cry. I make them go early to bed. They object. I kiss them. After ten o’clock at night all the women in my family are sleeping. Some under the pine trees, some under lamps. Barefoot or with shoes on their feet. They are sleeping, and sometimes they touch one another.

In the morning these children push their hair into my nose.

In what could have been a grueling, tragic account of cancer, Hair Everywhere achieves something more difficult: tenderness without pity. Tulić’s use of autofiction is neither egocentric nor exploitative of her experiences, but does precisely what a novel should do—it reveals something about our common humanity. She mines her own family history with a startling and mature emotional intelligence, producing an unblinking and largehearted collection of observations—on family, on women, and on growing up.

+++

+