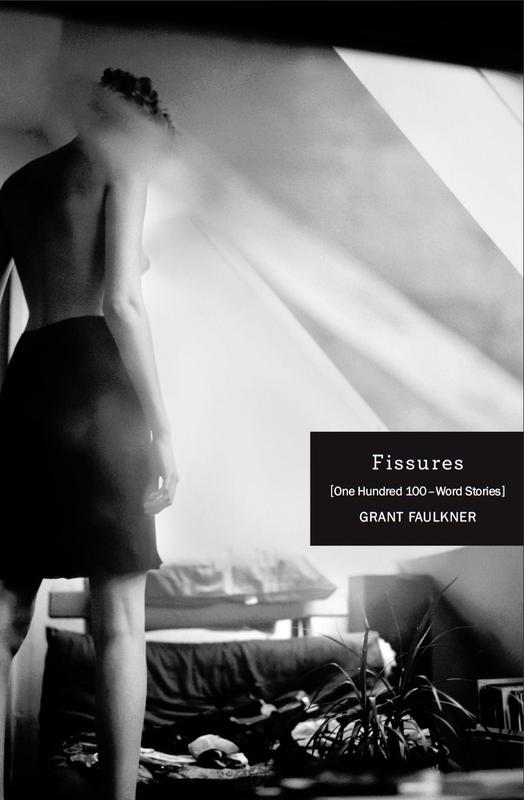

Press 53, 2015

Grant Faulkner is a contradiction. Executive Director of National Novel Writing Month, which challenges participants to complete a novel in one month, he also co-founded the journal 100 Word Story. He understands the value of both: the frenzy in pursuit of word count and the meticulous compression of story.

In Going Long. Going Short., from The New York Times Opinionator’s “Draft” series, Faulkner writes that flash fiction “communicates via caesuras and crevices. …it can perfectly capture the disconnections that existentially define us, whether it’s the gulf between a loved one, the natural world or God.”

It is these gulfs that Faulkner explores in Fissures, his collection of 100 stories of 100 words each. Fissures aches with countless stiff-lipped heartbreaks. The stories live in the space between words. This is, he argues, how we live. He writes in the preface:

We live in odd gaps of silence, irremediable interstices that sometimes last forever. … We all carry so many strange little moments within us. Memory shuffles through random snapshots.

And indeed, reading Fissures takes on the feeling of memory: glimpses, moments. They are scenes of impact and intersection, unencumbered by preamble or chronology. The meaning, what hovers in the air above the page, is vast.

Faulkner’s language is alternately beautiful and provocative, always precise, as is required with such a strict word limit. In “Take Four: Cocksam”, one of a series about Alexander, an underground filmmaker, another man recalls their first meeting, at a San Francisco brothel. While he waited, he imagined “Alexander’s whinnying red cock spitting at the girls.” It’s a jolt that tells us a lot about these characters.

While there is great diversity in subject matter and setting within these 100 stories (another series takes us to the Peruvian jungle), some of the most compelling feature Celeste and Gerard, a couple whose doomed love story appears throughout the collection. In “Souvenir,” Celeste emails “tracks of yearning, sexy songs” to the married Gerard. She imagines them popping up on his iPod in front of his wife, someday in the future. Celeste stakes a little claim to him, the memories of her these songs will evoke: “True lovers are expert in constructing penitentiaries. She’d hammer a nail into his hands for eternity, even as she listened to static.”

In “Drinking Martinis in Jelly Jars,” George and Margery have a cozy married life, with “boiled lobsters over a driftwood fire” and dozing on the sofa to Vivaldi. But when their dog Beau runs off, and Margery calls for him in a sing-song “Yooo hooo” that rankles, “George asked himself what call he answered to.” Faulker trusts his reader to understand this existential longing, this irritation with a presumably lovely spouse. At the end, still searching for their dog Beau, George “counted the women he’d kissed in his lifetime. Twenty-three. Never enough. Go Beau, he said under his breath.”

Fissures are not only found in romantic relationships, of course. In “Fatherhood”, Quentin touches the cracked face of a gold watch he gave his son:

He wondered what had caused the face to crack. A fall on the ice. A fight in a bar. An argument with a girlfriend. A father wants to know his son … What questions to ask?

Questions fall into the fissure between father and son. They live in the literal crack of the watch face. Quentin sees the damage but not the cause. He longs to know his son as a man, another link in their family’s chain, but is mired in silence.

In “Artifice”, Celeste and Gerard discuss museum guards, whether they are “enlightened,” “bored,” or simply “beyond the realm of passions”. Lying in their hotel bed, Gerard thinks:

The guards stared impassively into space, no matter the wild thrusts of the art around them. They waited, kept watch, much like he’d wait later that evening with his wife in the chaotic clatter of their house. … He was there only to make sure nothing broke.

“Artifice” demonstrates how much story Faulkner can deliver in 100 words: the comfortable intimacy of Celeste and Gerard; the staring guards, as disengaged as Gerard feels when home with his wife and their implied children. Lies are treachery but so is silence. The artifice of distance is employed by each of us at some point, or chronically. It is a survival skill that keeps us from getting what we need.

The ultimate disconnection, suicide, is suggested in the story “Making Music.” It begins, “No one heard that last faint guitar twang from Charley Dare’s studio apartment…” The narrator says, “If his parents would have listened to the cassette tapes they found when they cleaned out his apartment, they could have heard the song.” Perhaps the song would be an answer, not an explanation but a glimpse of their son as he truly was. But we know his parents won’t listen. Charley’s song won’t be heard. It will remain a “single lonely twang looking for something to cling to.”

In some of these stories the appeal is particularly sensorial, but these are never vignettes. In some, like “Shirley Temple”, the scene is so lushly conjured as to feel cinematic, and certainly the seed from which a longer work might grow. We have the world of a child in one moment:

I sat at the bar, my feet swinging from a stool. Jacksonville, 1972. The adults crowded into a circular booth in the corner. Men pinched women. Women squirmed in squirmy dresses. I smelled the chlorine on my hands as I listened to the cackles of laughter.

Faulkner takes a broader socio/political perspective in “The End of the World Will Be Broadcast.” Even at the literal end of the world, his characters seek connection as they watch from a distance: “The way the world was falling apart held beauty if viewed right.… He sat on his porch staring through his opera glasses.”

“Ambitious” is a word usually reserved for lengthy works, but it applies to Fissures because of how ambitiously Faulkner distills big stories and ideas into 100 words. They hold the larger story, the meaning, in the silent fissures. These are morsels to be savored, considered as they’re digested. Readers may wonder how many novels Faulkner may have seeded here and how many months it will take him to write them all.

+++

+