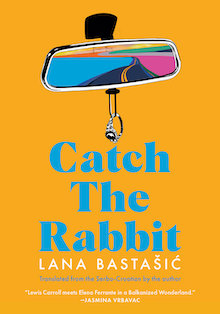

Restless Books, 2021

In Lana Bastašić’s tale of two school friends who meet after several decades to drive across Bosnia, a phone call from an old school friend jolts Sara, a Bosnian now living in Dublin, backwards in time to the Balkan wars. Lejla, who has changed almost everything about herself including her eye colour, imbues every scene with recklessness and opacity; whilst Sara, who narrates, seems unable to pin down the details of the trip on which she finds herself. Instead, she succumbs to the ride, which she intersperses with flashbacks to their schooldays.

The story itself is secondary to this beautifully written, dreamlike account of a journey. Though much is left unsaid, and what is revealed frequently confuses and contradicts, the novel is a backwards unfolding of two lives scarred irrevocably by the Bosnian war. Bastašic’s imagery is cinematic and kaleidoscopic, and so the conflict appears symbolically in crosses that “sprang up and spread like weeds: in backyards, on rear-view mirrors, around our chemistry teacher’s fat neck or tattooed like on Mitar’s dad’s biceps.”

Sara was born the day Tito died. Her journey zooms in and out of time, giving glimpses of the war’s horrors and atrocities through her schoolgirl eyes — the killing of dogs, the changing of names, and the disappearance of Armin, Lejla’s brother. Sara admits she “invented stories,” and we are never entirely sure what is true and what is not. Like a child processing trauma, she revisits certain thoughts and themes obsessively, reframing memory in a way she hopes will make sense of what has happened to her, and to countless other children, during wartime. She acknowledges that she “started writing” because she “needed to have something under my control, to be a god of certain small worlds … as long as one word followed the other, there was no point in stopping and considering the question of responsibility.”

Like most road-trip novels, the fascination lies in the journey rather than the destination, and this warren-like journey, echoing the rabbit that symbolises their hunt, is mysterious and compelling. The quarry is Lejla’s brother, missing for decades, with whom Sara had, as a schoolgirl, been in love. As Leila cannot drive, she summons Sara, across time and distance, to chase him down by car. From that first phone call, Lejla is an extraordinary character. How she reaches Sara’s Dublin mobile after years of silence is never explained. She frustrates: Her personal habits are disgusting, and she rarely answers a question. She “would sneak between two sentences like a moth between two slats of a venetian blind.” She sticks her chewing gum onto the back of Tito’s armchair in the AVNOJ Museum, and so the reader must accept her: equivocal, iconoclastic, and impossible to pin down.

Bastašić, like Beckett and Nabokov, translates her own work. Straddling two languages, her writing is surreal and rich. Words and language are like extra characters. When Sara answers the phone on St. Stephen’s Green, she says “yes in a language not my own.” Considering how she will tell her lover that she must go to Bosnia, she will plan “the words in a foreign language, weave and twist them so tightly that not a speck of light can slip through the threads.” The second person is used frequently, inviting the reader to eavesdrop on private conversations with Lejla. The theme of language is woven cleverly throughout the book, from the game the girls had played as teenagers, guessing each other’s obscure book quotes, to Lejla suddenly claiming to a landlady that Sara only speaks English. The story bristles with surreal metaphors, several to a page. A church shines “like a freshly polished coffee grinder”; “the heat squeezed into the car like a terminal illness.” They add to the impression of the author trying to make sense of the things that happened to her, to Lejla, and, of course, to Armin.

Identity is fluid and changeable, adding another layer of uncertainty to Sara’s memories. Names change: Armin, accused of killing a neighbour’s dog, becomes Marko before he disappears. Lejla removes the ‘J’ from her name, dyes her hair, wears coloured contact lenses, changes religion. Sara has created a new identity for herself in Ireland. Throughout the trip, darkness falls, heavily and unexpectedly, at odd times. Sara, driving across Bosnia, finds time distorted; the numbers on the car clock and Lejla’s old-fashioned Motorola screen are elusive and elastic. Sara’s dreams are vivid and strange. Death is everywhere in dead animals — the rabbit, a sparrow, a pig, dogs. The story itself feels constantly out of reach; perhaps on the next page, round another corner, in the morning, we might understand what happened, what is still happening.

This is a haunting book. Both girls hang around in the reader’s heart and imagination long after the last word. Like the Balkan conflict itself, the story is endless, looping, at once unreal and very clear. The flags in the AVNOJ Museum “lay flaccid, free from rogue winds — nothing could wave them anymore,” yet the war will stay with Sara and Lejla. Whatever countries they go to, however much they try to change themselves, it is in their bodies and memories, and that, perhaps, is the real story.

+++

+