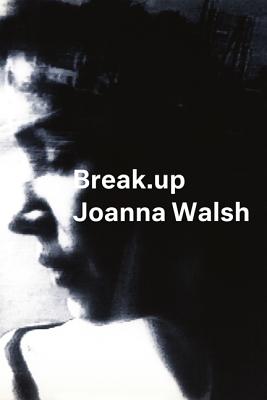

Semiotext(e), 2018

I’ve been dipping in and out of Geert Mak’s mammoth In Europe (translated by Sam Garrett) for the past couple of months. Crisscrossing the continent, Mak follows many strands of the twentieth century: what led to conflicts and what resolved them; which cities were in ascendance and which in decline; what forces rippled across the borders of nations. I wouldn’t usually begin a review of one book by describing another, but the experience of setting aside the long-term reading project of In Europe for a couple of intense, rapid days spent with Joanna Walsh’s new “novel in essays” Break.up seems to require it.

It also requires acknowledgement that while I’ve never met Walsh, I have published her writing here at Necessary Fiction and we are, perhaps, “friends” in the manner of strangers on Twitter. With a different book that preceding fondness, albeit at a digital distance, might prevent me from offering a review. In this case, however, such connections seem inbuilt to the project.

Break.up follows narrator “Joanna” as she travels from London to Paris, Rome, Sofia, Berlin, Amsterdam, and elsewhere on a switchback of Europe. It’s a travelogue, on its surface, but also the record of recovery from and reflection on a recently imploded romance. The affair itself took place mostly online, disembodied, so there’s also a ghost story here: she is haunted by the loss of something that was rarely “present” in several of that word’s meanings. Where Mak is both trailed by and trailing the phantoms of big-H History, Walsh explores a personal past only ever as distant as her new, shiny laptop cum travel companion:

The married state they still say in some wedding services, a solid state, the opposite of action. There are no moving parts in the solid state disk that runs the new laptop I have brought with me. It stores data “persistently” and constantly rearranges its memory in a non-linear pattern, recycling the past as the present. Its information cannot be permanently overwritten, except by special procedure but when it breaks, more often than not, all data, the whole story, disappears. I can’t begin to describe the silence at the heart of marriage, and I’ve been there.

Instead of a Europe of major dates and grand figures, Joanna’s is a continent of loose associations and friends of friends. There’s a drifting quality to her travel, a lack of explanation as to quite how her route has been chosen, that suggests it is as straightforward and as complex as going where she knows someone or knows someone who knows someone willing to put her up. Her trip is an embodied, offline performance of the drift many of us perform every day when we descend into the warren of being online, never quite knowing where and via which links we’ll end up.

Break.up’s Joanna — and again, this question of how to read the narrator’s and author’s shared name is no more or less than how we learn to “read” anyone we know only online, through “the airless twitter in which people have no husbands, wives, families” — is both in the places she travels and distant from them via email and memory alike. The book explores that distortion of being within and without simultaneously but never at the expense of simplifying or demonizing the digital: yes, traveling with a smartphone is different, but is that a difference of type or degree? Could we ever truly leave home behind when we traveled, or was “being there” always as tangled as the notes I tried to thumb-type on my own smartphone while reading Break.up on a crowded train car, so it would sync with a paired app on the laptop just inches away in my bag and have those notes waiting for me where and when I sat down to use them, but now can’t decipher:

Of being and not being in places, digitally or never leavidddd((ei ong at Germain for Paris, of brexit

The ghost of me-the-reader has let down me-the-reviewer, but he still haunts what I’m trying to say just as the past haunts the present on Joanna’s travels:

From Thessaloniki I meant to continue by train but found the railway system collapsing: price rises, staff laid off. With more miming, more scribbles, more silent offering Euros and pointing to maps, I crossed the city by bus to the coach station only just in time to catch that day’s one connection. All morning the Sofia coach followed the railway. Ghost carriages, orange with rust and graffiti, clogged the track. […]

And suddenly there was a sign for Sofia. I’d been asleep. The railway was gone and we raced tram lines into the city, the coach shaking, I didn’t know why. Wait. Yes: we were on cobbles, the present rattling over the past.

Break.up develops in fragments, reminding me at times (quite happily) of recent hybrid novels by Olga Tokarczuk and Dubravka Ugrešić. The book’s most present momentum comes from travel itself, from setting out toward and arriving at destinations. But just as in actual travel the thoughts and threads that spin out along the way are what make the trip, considerations of boredom and André Breton’s Nadja and the narrator’s own former marriage preceding the more recently broken romance. Those considerations and concerns are often marked by quotes and citations, not as footnotes or endnotes we readers might ignore but as insets shunting the present paragraph off to one side, insisting we pause for a moment and take aboard the stowaway texts as fellow travellers. And as in the passage above about laptops and marriage, those threads loop and echo, recurring and resonating across the book. The form is the experience, as with the once-common aerogrammes recalled by the narrator that folded to become their own envelope after the page had been written.

Walsh’s novel asks questions that aren’t necessarily “new” — about, for instance, the relationship between events as they happen versus how we imagine then remember and reconstruct them. But they are inflected differently for a networked age as she asks them through a hybridization of genre and form, and of author and character, that makes such questions more than academic: they are the stuff of our modern lives, of modern travel and modern romance, complicating the reading and writing of literature as they complicate everything else. I can already hear the echoes of Break.up as they will sing in my memory when next I travel to some of the same destinations “Joanna” visits and upon which, presumably, Joanna the author also set foot. I will perhaps be unable to resist rereading these pages in the very places they describe and deflect, complicating its questions still further, but isn’t that always the promise of travel and reading and writing alike?

+++

+