tr Celia Hawkesworth

Peirene Press, 2022

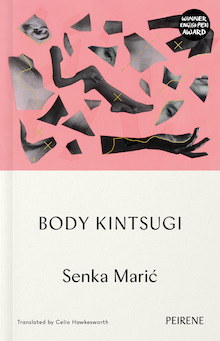

The centuries-old Japanese artistic technique known as kintsugi involves repairing shattered objects with liquid gold. Kintsugi translates roughly, and poetically, to “golden joinery.” Imagine ceramic vessels spiderwebbed with gleaming yellow: broken dishes are not only made whole again but enhanced, interwoven with lustrous precious metal. In her autobiographical debut novel, Body Kintsugi, Bosnian writer Senka Marić traces the scars that result from a breast cancer diagnosis and subsequent, increasingly invasive treatments. As Marić’s narrator faces her body’s vulnerability and her spiritual indestructibility, she discovers that these essential qualities coexist and even rely on one another.

Marić’s first book translated into English, it is utterly immersive and propulsive, with a style and structure that defy comparison. Hawkesworth’s fluid translation showcases the unique qualities of Marić’s poetic and intimately second-person prose. She writes, and Hawkesworth translates, as if they’re telling you a story about yourself; the narrator’s circumstances could easily be the reader’s. One chapter begins, “You knew on that day, sixteen years ago, when your mother’s diagnosis was confirmed, that you’d get cancer?” The next: “You were a sad child?” There’s a pause, a moment of uncertainty, and then: “That’s how it seems now.” The protagonist probes her audience. Now, remind me how it was… she seems to say, as if her readers already understand her, as if they are equally expert about her past.

Interspersed with the core narrative—of family life and hospital visits in Zagreb and Sarajevo—are technical passages about anti-cancer drugs and their side effects. These passages, which read as if they have been excerpted from warning labels, contrast powerfully with childhood memories and haunting dream sequences that feature cloaked ancestresses alongside familiar women of Greek mythology: Medea, Medusa, Penthesilea, and the Amazons.

Through these interstitial dreamscapes and reflections on childhood, Marić examines her narrator’s relationships to fear and care. When she is still small enough to fit under her grandfather’s desk, the narrator is overwhelmed by her fear of a black-and-white bogeyman who waits behind the curtain at the bottom of the stairs, a fear only remedied by the presence of her grandmother. At eleven, the narrator finds the hallways of a new apartment resemble “the intestines of an enormous animal” in which she has been swallowed. Her fear surrounds her “like tar,” and it is the old woman from the first floor who soothes her by offering sweets and stroking her hair.

When the narrator’s childhood bogeyman returns as an invasive cancer, both physical and emotional care are more difficult to come by. Her husband leaves just before she discovers the swollen lump between her breast and armpit. A lover offers only the occasional pleasure. In her dreams, the gods and ancestresses insist, “You can die in a million ways, but it doesn’t mean you won’t stay alive.” Care must come from within; it takes the form of stubbornness, determination, resilience in the face of slim odds and bodily horror. Marić describes the procedures to which her narrator is subject––and their side effects, their aftermaths––in direct, gruesome detail, refusing to shy away from the all-consuming reality of illness.

With each new operation and therapy, Marić leads the reader through the stages of a body’s transformation while presenting a mosaic of the protagonist’s past through the parts of her body. Marić’s protagonist is a woman at forty-two connecting shamelessly and with immense clarity to the experiences of her past selves.

In Bosnia’s patriarchal society, the narrator’s body in girlhood feels to her like a vessel in which she is trapped. She climbs out at certain moments—as when fighting her younger brother’s bully—only to be imprisoned again by the admonishing gazes of her parents: “They summon you back into the good little girl from whom you had tried to escape.” She recalls the way her grandfather held her foot to comfort her as she fell asleep and remembers when her alcoholic father lost his left toe and right leg. At eight, she came across a stash of pornography and for the first time learned how bodies can be entwined, a memory recounted with Annie Ernaux-like meticulousness and honesty:

The double bed is pushed up against the wall. There’s a bedside table on the right-hand side. On the right-hand wall, beside the door, there’s a wardrobe, and, behind you, and window. You don’t remember whether there’s anything else in the room. You do remember that the walls were pink and the bedside table white … You know this has to be a secret. You quickly put it all back where it was, frightened by the warmth between your legs. By that awakened centre of yourself. You clench your fists waiting for it to pass … And you run away. And then you persistently forget. Although you return to it still more persistently. To enjoy the warmth in your body and hate yourself because of it.

After an operation, one of many, Marić’s narrator observes, “Pain can’t get to you any more… It’s temporary, you are eternal.” She endures, waits, survives. With stomach-churning honesty and deep lyricism, Marić’s Body Kintsugi maps how an individual can be broken and remade by pain. Only when her narrator is “criss-crossed with scars” and “everything seems to have cracked” does the opportunity for beauty arise. This body is “enchanting, beautiful and soft, self-contained,” a body that has been “perfectly sculpted through all your defeats, and your victories,” where “the scars scrawled on it are a map of your journey.” In Marić’s novel, chemotherapy, surgery, and her narrator’s strength are a form of kintsugi: fragments of a body are made beautiful, repaired with gold.

+++

Senka Marić was born in southern Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1972. She is the author of three poetry collections and two novels: Body Kintsugi (2018), and Gravities (2021). She is also the editor of the online literary magazine Strane. Body Kintsugi was awarded the Meša Selimović Prize for the best novel published in 2018 in the region of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro.

+

Celia Hawkesworth taught at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL, from 1971 to 2002. She began translating fiction in the 1960s and to date has published some forty titles. Her translation of Ivo Andrić’s Omer Pasha Latas won the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation prize in 2019.

+

Regan Mies lives in New York, where she is an editorial assistant and recent graduate of Columbia University. Her reviews and short fiction have appeared in Necessary Fiction, On the Seawall, Litro Magazine, Quarto, and Columbia’s In the Margins.