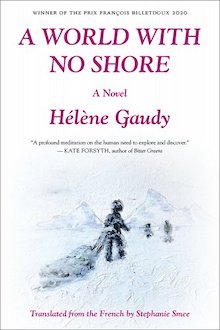

Zerogram Books, 2022

In 1887, three men disappeared while attempting to reach the North Pole by hot air balloon; thirty years later their remains are found on a bleak, frozen island along with rusted canisters contain photographic film. Some is undamaged enough by its three-decade-long incarceration in ice to allow experts at the Swedish Royal Institute of Technology to painstakingly develop the photographs. In A World with No Shore, Hélène Gaudy imagines the three men into an existence that feels at times as ephemeral and blurred as the photographs developed in 1930. She weaves their story with hesitant delicacy and deep respect, verging on obsession; her intensity matches their own.

The palimpsest of their figures—part tailored dandies who packed champagne and whose balloon was made of pink silk, part beard-swamped, snow-blackened, ice-bitten lost explorers—swims tantalizingly before our eyes. Gaudy’s historical accuracy is compulsively detailed; every scrap of story, like the frozen remains of their clothing, which was cleaned and polished and analyzed and recreated, is carefully laid out. The elements of costume, equipment, food, sights, sounds, weather are all displayed, discussed, curated. She reads everything ever written since their disappearance, and she acknowledges that the unknown, in certain people, evokes obsession, firing the imagination of anyone who scratches the surface. “[T]here are mysteries to be unravelled, lives to be imagined,” she writes. There is “an underground chain” of “scientists, computer experts, writers, the curious who in that enquiry find some convoluted way of looking deep within themselves, scratching where they didn’t know there was a wound.”

We are present throughout this journey; we see the actors, the light, the costumes, the slow sad death of the pink balloon whose fate was sealed by needle pricks and all the layers of varnish that could not stop its imperceptible deflation, and eventual abandonment, buried under snow. The travelers sing drunkenly on the twenty-fifth birthday of one of them, a man named Nils; they sing again on the day the new Swedish king is crowned. They consume so much bear-grease they stink of it; the bear skins they sew into increasingly bizarre costumes. Over their shoulders we read their notes on the movement of ice floes and letters home to a sweetheart. Gaudy’s masking of certain details mirrors the snow-blindness she imagines slowly overtaking the expedition’s leader.

But this book is so much more than the story of a doomed expedition.

It is, first of all, a love story. Anna waits for Nils to come home and marry her. When it eventually becomes clear his return is as unlikely as his flying in a balloon across the North Pole, she marries an Englishman and moves country. Thirty years later, when the bodies are discovered, she is stunned to see the face she loved staring out from a newspaper page. The shock abates, but she does not attend the state funeral. She sends a wreath, “to Nils, with love from Anna, one last time” and hatches an astounding plan from which no one, not even her husband, can dissuade her. When she dies at the end of the 1940s, her body is to be opened, “her heart removed from her chest and burnt, its ashes deposited in a silver urn right next to Nils’ remains, in the same grave, in Stockholm’s Northern Cemetery.”

Among items recovered from the place the bodies were found was a cache of letters Nils wrote to Anna, letters she did not see for thirty years. In one, he describes a dream he has not long before he dies (probably killed by a polar bear, still wearing the locket with her likeness he’d worn since leaving Stockholm). In the dream, he is running to meet her in Stockholm. She is out of reach, just beyond his outstretched hand. Writing from the ice floe upon which the stranded trio must now winter—hopelessly off course, running low on candles, and with a paraffin stove that’s beginning to malfunction—he remembers the streets of the city. His birthday, a day that started with songs and speeches, was marked by him falling into freezing water and ends with cake and chocolate. He concludes, “well then, that was foolish.” For her, and perhaps us, eavesdropping on a letter never intended for publication, the words must have rung with heartbreaking irony.

Along the way Gaudy muses on landscape, exploring how cartography can become part of the body as elements etching themselves onto it, changing the colour and texture of skin, hair, even teeth. She suggests that the landscape of the story is as alive as the three men attempting to cross it. She points out the hubris of attempting to conquer inhospitable and utterly foreign nature and raises questions about the nature of travel. Who are you when you are no longer in your home? What cultural baggage do you carry or leave behind? She examines the experience of those who go, and why, and those who stay behind. The rejoicing over the coronation of the new king by three men—blackened by ice burn, shuffling in bear skins, drinking champagne and raising flags just days before they die—is as surreal an image as one could imagine.

+++

Hélène Gaudy lives in Paris. She was born in 1979, studied at L’École supérieure des arts décoratifs in Strasbourg, and joined a literary group that publishes as the Inculte collective. She is the author of six novels—most recently, Une île, une forteresse (2016)—and a dozen books for children.

+

Stephanie Smee left a career in law to work as a literary translator. She recently translated Pascal Janovjak’s The Rome Zoo (2021).

+

Educated in the West Indies, Saudi Arabia, Scotland and Belgium, Elizabeth Smith studied modern languages at Durham University in England. She reads anything she can, especially pre-war books by obscure women and modern European writers. She lives in an old house on a small island where she often pretends it is 1936.