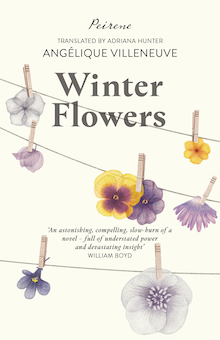

translated by Adriana Hunter

Peirene Press, 2021

Jeanne, expert crafter of artificial flowers, is on a tram in Paris in 1918. A soldier with horrific facial injuries enters her carriage, causing the crowd to “turn and flinch away … half-pitying, half-appalled … The whole structure of his face has been destroyed.” The passengers, electrified, react with horrified sympathy; children are exhorted to look on this brutal badge of patriotism; all around “intact faces” wear sad smiles “like monstrous grimaces.”

To these onlookers, this desperately disfigured young man symbolises the horror and violence of the war. But he has not died. His family is spared the presentation of a certificate lauding the supreme sacrifice by the mayor of Paris; instead he must try and reconstruct a life, finding a way to eat, to earn a living, to forge relationships, and to exist with a face that has been blown wide open.

The irony of the tram scene is that Jeanne, who survives the war mourning one child and feeding her remaining daughter on bread soup, has a husband who is also unrecognisable. Toussaint returns from the war with a white cotton mask. Like Jeanne and her daughter, this slim, moving novel looks obliquely, through partially opened fingers, at this silent survivor.

Disfigured beyond recognition, Toussaint stands for a long time outside the door of the small apartment where he once lived happily. Inside, his exhausted, near-starving wife creates beautiful silk flowers for rich women to wear on hats, a process that stains her mouth with toxic dyes, leaves a constant red welt under her ribcage, and renders her sleepless as she tries desperately to produce enough flowers to keep her remaining daughter alive. The room is a close, chilly set of half-made flowers and hoarded, half-eaten scraps. On the one hand, there is the photograph of the handsome man who went to war; on the other, there is the silent form under the bedclothes who returns, forbidding his wife to touch him, or even look too closely at the stained cotton mask covering what was once his face.

In this intensely female novel, women, mothers, sex, domesticity, drudgery, indignity, and solidarity are highlighted by Jeanne’s efforts to survive the privations of war. The female experience is presented alongside the imagined action of the soldiers. Both men and women are equally eager to get to the other side of the war as sane and intact as they possibly can. Beyond that, Villeneuve refuses to offer pat answers or tie up loose ends in obvious ways. When Jeanne’s neighbour steals some poppies, we are to infer that she resorts to theft only because her son has been killed and she has grown mad with grief. The flowers in this novel become characters in their own right; the stolen poppies symbolise war, loss, remembrance, and artifice.

Generally, however, the characters reveal very little of their inner worlds and their actions give scant clue to their motivation or intentions. Communication sometimes happens in notes or by gesture. There are long, heavy silences — while Toussaint lies silently in bed, Jeanne becomes suddenly unable to hear the cries of her neighbour whose son has been killed. At the same time, whole chapters are filled with rumour, hearsay, gossip. “Word is people are growing beans and carrots on place du Panthéon … word is they threw sweets stuffed with typhus and cholera from their aeroplanes.”

Thanks to the novel’s dreamlike, truncated sense of time, it is not immediately clear what has happened to Toussaint. We cannot even be sure if the man who has returned is really him. Jeanne longs to rediscover her husband, who remains apart and hidden; she must breathe his scent and talk with him through her skin, through touch. On every page we are forced to ask: If you cannot see someone’s face, how do you know them?

The answer becomes irrelevant as the scenes unfold. We grow unsettlingly close to the reunited family, struggling back from national and personal chaos. Setting the majority of the scenes in the small apartment thrusts the reader into the most intimate events, heavy silences, and sudden bursts of emotion; we, too, are watching, waiting, and listening. We cannot remain indifferent to characters we know in such raw states. We leave them at the Armistice, feeling their way tentatively and hopefully towards knowing each other in new ways.

+++

+

+