Small Doggies Press, 2012

If I had an ounce of poetic talent, I’d write about J.A. Tyler’s Variations of a Brother War by mimicking its form. I’d create this review out of bundles of stanzas, introducing each bundle with a stark and intriguing theme, and then I’d hypnotize you with unusual comparisons—I might call the book a bird whose word feathers grow long from chains of letters that pocket the air in their hollows and carry the story aloft. Or I’d try to enchant you with circular and layered descriptions—I could tell you that this is a book about war and then tell you that it’s really a book about baking bread; I could write the review in three different voices, some of whom only speak through silence; I could convince you that the story is as old as forever but then prove it’s newness in my next breath.

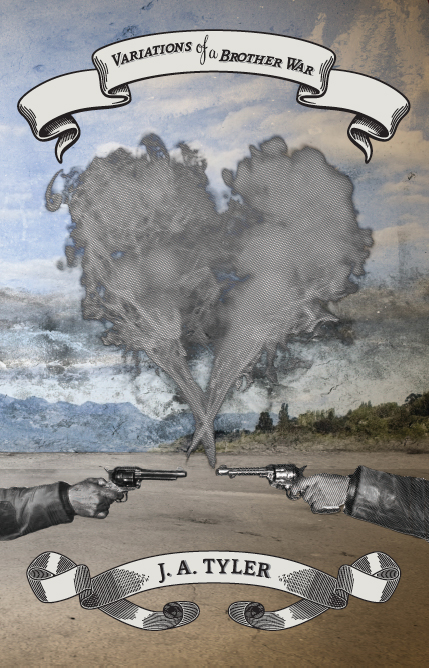

But I won’t do any of that. I will leave the poetics to J.A. Tyler and get down to describing the experience of reading this tightly constructed novella-in-verse, a book that is a début, but not for the well-published and well-known Tyler. By début, I mean that it is the very first offering from Small Doggies Press, the publishing arm of Small Doggies Magazine in Portland, Oregon.

First, the story. Variations of a Brother War is about Miller and Gideon, two brothers in love with the same woman.

Eliza Was a Girl Between Two Men

In the river are rocks worn smooth by water. Eliza between Gideon and Miller. Both in button-down shirts. Both recklessly hoisting rifles, carving trees with bullets, spearing through the ribs of other men. For Eliza there are no other men. For Eliza there is a sun and a moon. For Eliza a snake and a warm rock and a latch and a key are obstacles in the way. She is in love with Miller. She is in love with Gideon. For Eliza, war-field shrieks are birds singing, trees are for shade, and men are in-between how she can continue this.

It is also the story of a country at war, of families struggling to live with greater and greater losses. It is the story of love discovered and love lost. It tells of men born from the same mother but who are as different from each other as the two sides in a bloody battle. It tells of men grown in the same country, but living vastly contradictory lives. Tyler gives his readers a Civil War setting and the story of a family at war – just one example of the novella’s many variations.

Second, the structure. Sometimes a rigid structure can restrain a long work of poetry, can force it to be something that the wildness of its interior verse must then fight against, but this doesn’t happen in Variations of a Brother War. The book’s repetition of three sequential stanzas, separated by a short title and then divided from the next triptych by an overall theme, does not stifle Tyler’s ability to write in a melodic but also powerful prose. The 100 word limit of each stanza is an impressive constraint that doesn’t once threaten to turn this novella-in-verse into something stiff or forced; instead the strictness of the word count and structure provide a very real and almost soothing harmony to what are often violent or unsettling mini story worlds.

In a Gouged Heart

Gideon’s first battle was when he stepped on the biggest flower in their smallest garden and his mother chased him from the dirt, bare feet kicking, her mother face closed down into winter. Gideon launching apples later from whipping sticks in the woods, the lashes on his back when he returned for dinner, his mother and her perfect teaching. Gideon now gutting one man who looks into his eyes, across from him, the concrete distance of a rifle to an abdomen, and his mother there in that man’s eyes, the apples whipping out, the flower crushed beneath his boyhood feet.

As the title suggests, there are many stories here in Variations of a Brother War, and of course there is only one story told in myriad ways. Gideon and Miller will die several deaths, Eliza will love both men and reject both men. She will love many times. She will be happy. She will be alone. Mothers die and fathers leave, both become ghosts who then return again and again to Tyler’s valley of cabins and rage and love-gone-wrong. Despite the strictness of the structure, the book offers a freedom of story and meaning, a chance to be read again and again in the joy of new discovery.

J.A. Tyler’s stylistic fingerprint is an unmistakable element of this work. Here is a writer who likes the language of dreaming, of unusual and sometimes mystifying descriptions— “Eliza, when she breathes rain into his fields, Gideon’s voice calms. When she is wrapped in his head Gideon runs through trees, spreading leaves, spinning their bodies as glass,”—descriptions that are certainly beautiful and inventive but also invite multiple, close readings. This is a book whose story is as much about the “story” as it is about Tyler’s playful and curious twists and leaps of language.

+++

+