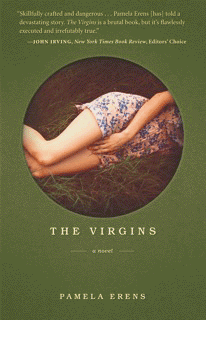

Tin House Books, 2013

Remember that couple at your high school or college who were always making out in public, who became notorious, perhaps envied, then eventually reviled, for “doing it” a lot more than anyone else? But were they? Or was the truth a lot more complicated than it appeared on the surface? Pamela Erens’s novel The Virgins is impressive for many reasons—strong narrative writing, suspenseful plotting and fully human characters—but perhaps one of the most remarkable things about it is her incredible knowledge of sex from the point of view of both genders. I regret this novel was not available to me when I was sixteen; however, it’s never too late to figure out what was truly happening at one of life’s most critical junctures.

The Golden Couple at the center of The Virgins have plenty of sexual difficulty, to which all readers will painfully relate. Aviva Rossner, away at boarding school, is newly bold. At her old school she was practically invisible but no more; she’s developed style in order to make a place in the world for herself in order to compete with her superstar professor mother (an unforgettable minor character). And Aviva meets her perfect complement in the athletic, Korean-American Seung Jung. Together, they manifest extreme sexual heat, looking all but naked as they make out for hours all over campus (and, eventually, in a hotel stairway in New York City).

So maybe you’re thinking: another clichéd coming-of-age story set at a boarding school in the late seventies: just another thinly-disguised autobiographical love triangle? We might think so for a few pages until the narrator, Bruce Bennett-Jones, driven a little crazy by the sexy Aviva, sexually assaults her, shocking himself before the feisty victim defends herself very well. Afterward, Bruce knows he’ll never have another chance for a real relationship with Aviva, so when the good-looking but otherwise average-in-every way Seung takes up with her, Bruce is relegated to watching, and that’s when things get really interesting. He’s beyond voyeurism, for, while he witnesses as much of the Golden Couple’s behavior as anyone else on the small campus, he can’t know the intimate details of their sex life together—so he invents what he can’t know. Thus, it’s through the imagination rather than senses of this highly-articulate “theater guy,” now much older and looking back, that we receive the public and private details of the couple’s relationship (which he tells us early on, ends in tragedy).

The analysis of sex and power afforded by this point of view is highly effective. Bruce is the perfect vehicle to dissect the dynamics of Seung and Aviva’s sexual relationship with almost-clinical precision—and in the process completely reveal the dysfunction of these two doomed young lovers. Who among us, male or female, doesn’t remember what it was like to yearn to lose one’s virginity, only to find the experience far from romantic, and ourselves far from competent? And that’s the gist of it: these lovers, for all their steam and apparent affection, if not love for each other, lack the ability to consummate, although everyone on campus assumes otherwise.

It’s painful—yet instructive and enlightening—to observe this volatile relationship, along with Bruce. As he says before we’re fifty pages into the novel, teen sex is much more about “metaphysical yearnings” than it is about “asses and crotches”:

. . . We beginners experienced sex as psyche more than body, as vulnerability and power, exposure and flight, being anointed, saved, transfigured. To . . . do it wrong was to experience . . . the death of one’s ideal soul.

That could easily stand as the book’s thesis, letting the readers know what’s at stake. Erens delivers on her implied promise to probe the sexual psyche, and the events she dramatizes are never merely prurient, coarse or clichéd. Her many revelations and insights ring sadly true.

To illustrate with one of Bruce’s fairly minor—but spot on—insights about kissing and talking: “ . . . a tongue pushing deep inside you was as fucked as you could possibly be . . .” and maybe even “more than anything that came later.” As for the talking that comes after: “Without it they would turn on each other, not be able to stand the pleasure.”

Such statements, offered by the mature Bruce, help us understand a ritual as old as time itself, but made so much more complicated by today’s crazy age—and worse than complicated, dangerous. Knowing the Golden Couple is doomed does not lessen the suspense at all, for the tragic conclusion is as surprising as it is inevitable. Another great satisfaction is that Erens doesn’t rush this story with so much at stake but gives herself ample time to develop the denouement following the sad climax.

The Virgins will surely fascinate and interest all lovers of literary fiction—but writers especially will be interested to see how she pulls off this difficult point of view challenge. If we hate the narrator, the book doesn’t work nearly as well: we’ll ignore any wisdom Bruce finds in looking back at his and the other characters’ horrific mistakes. Readers could be forgiven for wondering whether Bruce is merely the author’s mouthpiece, speculating ad nauseum about the couple with whom he’s obsessed. However, he plays an active role in the events leading to the tragedy. Significantly, I found the would-be rapist more sympathetic than not, willing to admit mistakes and shortcomings, accept the consequences and even regret them, recognizing himself as “someone filled with ugly and perhaps uncontrollable impulses.” It’s clear the grown-up Bruce would’ve behaved much differently if he’d had access to any of the hard-won wisdom he possesses now. Others might have a lot more trouble than I did forgiving his worst shortcomings.

I can’t recall a recent novel in which I was so thoroughly engaged as The Virgins. The fictionist in me argued with the narrator when he says that telling someone’s story:

…is at one and the same time an act of devotion and an expression of sadism. You are the one moving bodies around, putting words in their mouths, making them do what you need them to do. You insist, they submit.

I agree completely with devotion but . . . sadism? The people in my stories mostly tell and show me what they want to do. They mostly insist; I mostly submit—and I wouldn’t have it any other way. I suspect that, regardless of what her character thinks, Pamela Erens wouldn’t, either. But the above comment from the narrator does profoundly reflect on the novel’s sexual subtext of control. He could not have his way with Aviva, but he can control what readers know about her. Thus, there’s an impressive metafictional slide—Erens using a fictional character to tell a fictional story, but at the same time reminding us of the power of the author and narrator: the power to control, which is, after all, the novel’s point. Quite a feat—and a real feast for the reader.

+++

+