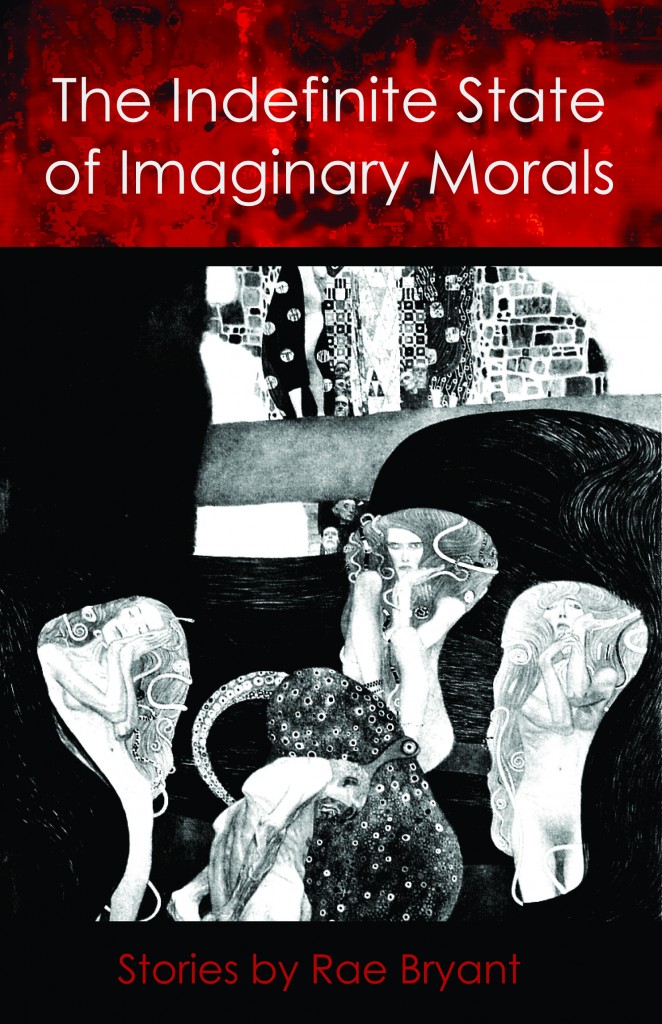

Patasola Press, 2011

The stories in Rae Bryant’s collection The Indefinite State of Imaginary Morals possess a certainty of voice and spirit that contradicts the volatile, undefined nature of the title. Bryant’s language is as lyrical as her subject matter is corporal. Her protagonists are largely (but not entirely) women who are struggling to relate to a man, to men, or to the world that undervalues them.

Sex is a kind of currency in these stories, as well as a conduit for emotional undertones. In the title story, which is divided into sections named for beverages imbibed, a woman finds a man alternately attractive and unattractive until she slips away post-coitus, dredging up a family emergency as the excuse for her hasty exit. In “Intolerable Impositions” a woman chews off a limb after “a tolerable sexing” to avoid waking him and being forced to play an undesired role in her new lover’s life. She briefly considers “loving him” but decides against the hassle, asserting that, “A single forearm was well worth the escape.” In “Solipsy Street” a struggling relationship falters as the narrator’s beloved takes her to watch him sleep with a junkie:

When you fuck, your legs are like albino eels, long and smooth, the crotch of your banana yellow short-shorts pushed to one side as you slide on the condom, push up her skirt. I imagine you are made of muffins again, you and the girl stuck together with cream cheese, and she grabs at you behind her, pushes her face into the mattress, breathes so hard I think she might asphyxiate. Her arms are bruised, beautiful. Yes, she is that too. I will give you that. You have chosen a beautiful whore. But—and I only say this for aesthetics’ sake, not to be cruel—for the front teeth. It is so difficult to tell the ages of your junkies.

Eroticism can also lead to tenderness in these stories. In “Fifty Years in Halves,” a relationship, and then a marriage, develops over a tradition of shared burrito bowls. The woman steals the last piece of avocado each time, engendering passion, annoyance, rage and finally resignation in both their minds. In the closing vignette the husband takes an active role in the tradition:

He takes her hand, squeezes it gently and watches her lips move, remembering their first burrito bowl and how she stole his avocado, how she was so jealous when he looked at a pretty girl with mango-soaked shoes. He smiles, lifts himself on feeble legs, kisses her withered cheek. Pinching the avocado with shaking fingertips, he lays it on her tongue.

Bryant writes in a style she calls “prosetry”—and her lyricism and cadence can transform the wretched into the momentarily sublime. The stories in this collection range from one-sentence prose poems to flash fiction, to more traditional short stories and visual art. Bryant’s voice remains vibrant in all of these formats, but thrives most when it delves into the fantastic, as exemplified by the opening passage of “I Keep a Vine Woven Basket by the Front Door:”

It sits like Mahagony veins twisted into themselves – a hollow of wooden pulmonary. Beneath the basket rests a Rubbermaid wet mat, sky blue, and I lay in it my twisted head ripped from its shoulders, snapped from its spine.

In this story the speaker holds a conversation with her womb as they reflect on the loss of a beloved pet, a fetus, and a man. In “City in Spires” a young woman struggles to avoid prostitution to be able to feed her younger brother in a post-apocalyptic world. Her visions bring sustenance to the city, but she is ultimately silenced.

Not all of Bryant’s stories center on women. In “Cow Tipping” an urban lawyer has returned to his childhood farm. A poker game with friends raises questions of race, loyalty and personal history. The poker game does, however, revolve around a deck of erotic cards. The cards, the basement and the poker night, are the lawyer’s last vestiges of masculine identity in a house overtaken by his wife’s Crate & Barrel fixation.

In “Shadow Spots,” the concluding story of the collection, a young girl is harangued by her mother after nearly drowning in a hotel pool. In reality, a boy has been harassing her, holding her head down. This fact doesn’t seem to affect the mother, who is busy with her own secrets. But after reflecting on, and in fact, reliving, the struggle underwater, the girl comes to a surprising realization:

She replays the incident in her mind, wondering how she might have done it better, avoided the embarrassment. Then she thinks: You stupid girl. Why didn’t you just swim away?

While the thirty-plus pieces in this collection do not always seem cohesive, they are certainly complementary. Bryant’s stories are reminiscent of Margaret Atwood’s early work; the female body, and female sexuality are transformative, electric, and dangerous. Sex is a negotiation for power, and it often doesn’t lead her characters to places that they, or we, expect. Those surprising, if sometimes disturbing destinations make up the crux of this collection, and are definitely worth a peek.

+++

+