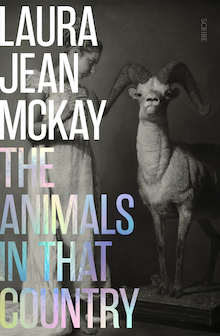

Scribe, 2020

We are enamoured with talking animals. In literature they have been there from the beginning, tempting Adam and Eve, guiding children through fairy tales, befriending Christopher Robin. The dream of communicating with other animals follows us out of childhood, from stuffed toys and Disney regicides to Orwell’s rich pigs and proletariat mules. How does a writer tread convincingly outside these realms of allegory and magic?

For Laura Jean McKay, the solution was, coincidentally, an epidemic. In The Animals in That Country, McKay had the strange luck (or misfortune, depending on how you look at it) of writing a virus novel just before our own year turned pandemic. The first time the flu appears in the novel, it is casually dropped into conversation between Jean Bennet, the narrator and park tour guide, and Angela, the park’s manager, only to be ignored.

‘Did you see the news?’

‘That flu.’

‘I’m talking about the break-ins.’

Jean later hears scraps of flu-related news over the car radio, but the focus is still on eco-terrorists and their plots to free “pets, farm, and laboratory animals across the south.” Then, on the TV at home: “Superflu has reached epidemic stage in only five days.” While McKay’s delivery of the news is filmic in nature, the response to it is unnervingly accurate. Jean watches the news and sarcastically asks, “So, who died?” Later, in a conversation with Andy, another park employee, talk of the flu is interrupted by a dick pic. The “zooflu” is a background noise until it’s directly at the front door, closing down the wildlife park and tripping up Jean’s daily routine.

Rough as sandpaper and shambling from day to day, Jean is in equal parts frustrating and warm, a struggling alcoholic who is deeply devoted to her granddaughter, Kimberley. In the context of an epidemic, she is difficult; she reads forum posts about soya causing the zooflu, and she argues with strangers online. McKay provides her with a voice that is salt of the earth and proud of it, and when it comes to it, unerringly loyal. She is the relative everyone has: the chain smoking, constantly cursing auntie or uncle, never far from spitting or hurting someone’s feelings, and who, despite making the kids a little nervous and the adults a little quiet, has never stopped trying to get things right.

The supporting cast — Jean’s son, Lee; his ex-lover, Angela; their young daughter, Kimberley — feels much of the time like just that: a cast. They move and talk in a stagey manner, and they are too clearly directed by the plot. Angela often speaks as if reading from a script, even when talking to her daughter. Lee, Jean’s free-spirited, charismatic son who spouts inspirational messages, seems clearly intended to be a stereotype. But when most of the minor characters feel stereotypical, the effect can be flattening. Even Jean has her weaker moments. In the last third of the book, directly following an episode of incredible trauma, she flirts over the phone, draining the scene of its heartbreak.

In the end, though, the humans are essentially receptacles, mobile vessels to be filled with the voices and the stories of animals. Once the story begins, after Lee practically kidnaps Kimberley and takes her to hear the whales speak, the novel becomes a long road trip through both Australia and its now-vocal wildlife.

In structuring her narrative around human-animal conversation, McKay takes a huge risk. Between learning what the “zooflu” is and Jean herself catching it, there is a moment when the reader’s trust could easily be lost, when it is easy to expect cutesy Dr. Doolittle-style court jesters. But from the moment the first animal voice is heard, it is obvious that these are not the voices asking to talk to us. When Jean hears her first animal, one of the park’s caged mice, it is a single word that bleeds into a stream-of-consciousness horror show.

Run

I look around. Someone said it, clear as speech. ‘I’m in here,’ I call out to Doug.

Run.

It’s glands from the

body. It’s crops

and

killing and shelter —

‘No, it’s…’ Who’s talking? ‘It’s just Jean.’

McKay does not offer us anthropomorphised cartoons, but a vocabulary formed by scent and breath. Animal “speech” is the product of their whole way of life, whether it’s a mouse in a cage or a magpie in the trees, and it often looks more like riddles than conversation. As Jean says, it is “like some language I barely remember from a high school textbook. Bonjour madame, connaissez-vous le chemin de la gare?”

As the novel progresses, and more animals are introduced, it becomes impossible not to believe in McKay’s creative choices. In the arrangement and the rhythms and the personalities of each animal she translates, it is obvious McKay withheld nothing. When a horse says to Jean, “A paddock/for a soft/hand,” you can hear its deep whisper; or when a huge maggot, about to be eaten, squeals “INSIDE, INSIDE” as demandingly as an addict, and once eaten, again squeals “INSIDE. WE’RE INSIDE,” there is no doubt that this is what a maggot cries. Every single creature sings, even the blowflies looking for food (“SUCK. / SUCK AND FUCK.”) Their language is both like and unlike our own, an oral literature of blood, sex and repetition, somewhere between a folktale and a dirty joke.

Even when she is just describing the way wildlife moves, McKay is an expert, capturing images as keenly as a poet. A dingo walks down a boulder “like he’s yellow water trickling downstream.” The face of a praying mantis is described perfectly, and unexpectedly, as “a leaf that fell in love with itself.” Perhaps it is unsurprising, then, that McKay’s humans feel somewhat abstract, when her gift for defining every and any animal is so pronounced. That same gift that sits at the core of the novel. McKay has not written a white lie about how lovely it would be to speak with a dog. Instead, she has asked that necessary, and uncomfortable question: Do we really want to know what the rest of the planet thinks of us?

+++

+