I warn you, I’m a sensitive man, at the mercy of whims and fancy.

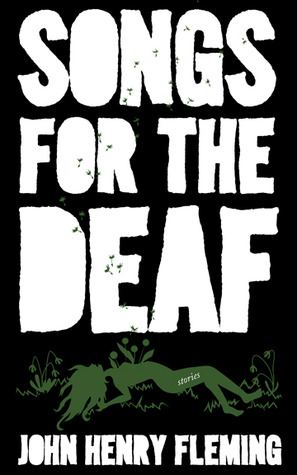

Burrow Press, 2014

John Henry Fleming’s first short story collection is a colorful gathering of misfits and metaphysical battles. In Fleming’s opening story “The Cloud Reader,” the title character is a clairvoyant outcast struggling against a fearful, conservative society. The cloud reader, in the role of the patient and clearheaded oracle, could tell them what he knows and what he sees of the world—if only they would listen. But they reject his muse-like invocation to be led out of their “uncertain world,” and the cloud reader is hanged beneath an oak tree. And so guide-less, we begin our journey into the strange world of Songs for the Deaf.

In these stories, nothing ordinary can remain so. The divine live and walk among us, and Fleming’s nonconformist characters are suspended somewhere between the earth and the sky. “The Day of Our Lord,” for example, is a contemporary gospel record of a teenaged, twenty-first century savior: “This is how Our Lord did persevere,” chants the narrator with sacramental reverence, and persevere Our Lord does against the bigger, jock-er Sworn Enemies on the blacktop of adolescence.

In “Weighing of the Heart,” the wandering narrator picks up a wayfaring girl on a barren stretch of road who,

…bounces and glides, bounces and glides, like a ghost who’s just become a ghost and still doesn’t know it.

The narrator is tasked with helping her find a way to tie her back to earth so she can move west and become a movie star. He assures her that even if she can’t figure out how to kick her floating habit, it won’t be a problem, because:

…when you’re a star you kick off the weights, rise up high as you like, and tell them they’ve got to deal with it. And they will, because then you’ve got star power.

As if being half-ghost weren’t extraordinary enough.

“Chomolungma” is also a tale of misfits on “a lofty spirit-walk,” this time featuring a dysfunctional modern family, nearly frozen to the side of the highest mountain in the world. After learning of his wife’s unfaithfulness, the family’s father spends his life’s savings to bring everyone on a trip to the top of Mount Everest. He, like many of Fleming’s characters, craves transcendence, a release from the world’s mundane and disappointing standards, but his family resent him for it.

“Why risk your life to be cold and out of breath?” protests his daughter. “To stand at the top of a stupid mountain just so you can tell everyone you did?”

Not until the story’s bleak, black end does the son realize the significance of leaving the rest of the world behind. Rising higher into the air, the son,

…can see now how life is sharpened to a dagger on these high peaks. One either uses it to piece the stupid façade, or else one gets clumsy and falls on it. So it goes.

If there’s a moral to Fleming’s fables, it’s that being different is lonely, and sometimes it’s fatal.

In the collection’s title story, artistic and arrogant Tony Sutter, the small-town singing wonder, sets his sights high on the peaks of fame and talent. He dons a cape and wears his hair long for reasons his classmate Jeremy Jones could never understand:

By all rights, Tony Sutter should have been the bottom-feeder in the social aquarium, the one who slurps filth off the stem of the plastic plant and the deep sea diver’s shoes. But there was that voice, and the voice had saved him. It had lifted him up just enough to leave Jeremy Jones alone at the bottom…

Like the floating girl, Tony’s own star power elevates him to an existence beyond that of his hometown, while Jeremy, the boy who never left, is left feeling as though he “had struggled his whole life just to feel part of the unlovely clatter Tony Sutter so loftily dismissed.” The story’s full and cleverly written characters question readers’ assumptions about what separates the masses from the misfits and how we all aspire to be one or the other.

Like the cloud reader, Fleming tells stories with the clarity and deference of a skilled interpreter, a fluent conduit for what the disenfranchised characters have to say for themselves. His stories read like modern-day folk tales that have only now been discovered and transcribed. At its offbeat heart, this is a collection of stories about convictions. Certainty, especially in one’s exceptional self, is a rare but priceless currency. “The world has unlimited powers to conceal and confuse,” observes the cloud reader. But refreshingly, there are things that the characters in Fleming’s stories find more valuable than ordinary acceptance. And there are stories, like “Songs for the Deaf,” that help ordinary people like us find them too.

+++

+