My grandfather was born in Leap, County Cork, in a house where the sea lapped the end of the garden. When bodies washed up from the torpedoed Lusitania in 1915, it was his mother, Ellen O’Donovan, also the area Registrar of Births, Deaths and Marriages, who escorted them by horse-and-carriage the forty-six miles to Cork city morgue. Though I grew up in a land-locked county, synonymous with horses not salt water, I have always felt that the sea is as much about genetics as geography, that salt water is something that is in the blood.

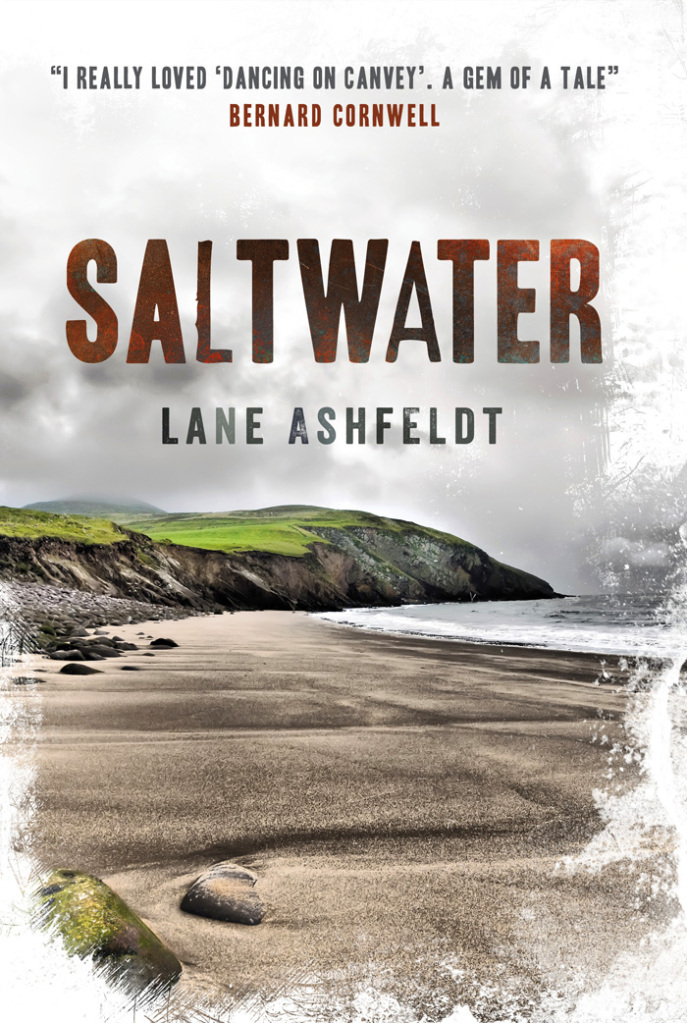

Says the ‘metadata’ of my e-book, “SaltWater contains a dozen or so short stories inspired by the sea, set in coastal areas from Ireland to New Zealand” and that “Lane Ashfeldt has lived and worked in many of the places where these stories are set.” The stories in this collection leave us in no doubt that Ashfeldt has the sea in her DNA, and from the first story we know that she also innately understands the fear and respect that the sea, rightly, inspires.

“Will she let you go?” Elizabeth asks her friend, Roisín, in the opening dialogue of “The Boat Trip.” Roisín’s response, “Sure John Daly’s the best skipper on Cléire,” makes clear the danger of the Roaring Water Bay crossing. We have been put on alert, so when point-of-view switches to the same John Daly, on the way back from Schull to Baltimore, with: “Carbery’s Isles are a danger to those who don’t know them…” we know to worry. When he, “shakes his head, tries again to find his stars. He doesn’t know he is sailing into a mist, a mist so thick the Baltimore fishermen have not gone out,” we are waiting for the catastrophe which happens just a few paragraphs later.

The neat link from “The Boat Trip” to the titular “SaltWater” comes in the person of Nola, now a mother, and wife to Jim. Ashfeldt exports the trauma Nola experienced as a child into “SaltWater,” and exploits it. Our warning comes in the first paragraph: “You had to be ready for the sea because, if not, then the sea would be ready for you.” Tension is then built in patient, skillful increments, with complete surety of pace: Jim is at sea, on his way from Cornwall back to West Cork; Nola first doesn’t want to take the ferry to Sherkin Island with the children, then changes her mind; we learn that Nola can’t swim just before the children’s “voices faded and their swimsuited bodies shrank to small blobs against the glare of the water.” The reader is on edge from different sides at once. Relentlessly, Ashfeldt increases the tension: Jim comes under fire from German fighter planes; Nola dreams of her drowned sister; she wakes and sees Rosannah, one of the children, in distress; “she entered the water.”

We are so riveted by the tale that it would be easy to miss the lyricism of the writing, the well-tuned ear for language, the well-made metaphor: “She awoke with a “blessed art thou” on her tongue”; the sound of the gunfire is “Ack-ack-ack!”; “the constant three-legged race of being part of a large family.” The dialogue throughout the stories is fluid and authentic, and never jars, though she covers places as disparate and far flung as Haiti and Australia and the West Cork of the past.

Her skill as a storyteller, and her control over her craft, is nowhere more in evidence than in “Dancing On Canvey,” my favourite story of the collection. The by-now familiar warning appears, again in the first paragraph. Gwynnie, the narrator is “not allowed” up on the sea wall, where, “the odd wave sends spray flying up, and the wind curls between my legs, snapping at the skirt of my school gabardine.”

Place is cleverly established through school art class, where the children are making a frieze of the island. Large quantities of historical and geographical information about Canvey Island are presented with the lightest hand via the lesson; we find out about Danish, Roman and Dutch influences, and the island’s history of flooding—our next warning—but it is all neutralised with, “will this come up in our 11+.” To which Mr Frome’s answer deftly draws us still further away from our clue: “The answer’s no. ‘But good handwriting,’ he says firmly, ‘is a skill that will serve you well whatever your future occupation.’”

Plot, place, character and desire are melded together in this school setting, introducing us to Johnny Deakin, more interested in fishing than handwriting, but grateful to the narrator for helping him. There are the beginnings of sexual attraction for Gwynnie as she walks home, “trying to work out what it is about those brown eyes of his that make me uncomfortable,” only to find that Johnny is walking beside her.

It is Johnny who leads us into the next part of the story:

“Moon’s just off full. They’ll be gawping at it on their way to the dance tomorrow.” He laughs, then looks me in the eye. “You going? Nah, you’re too young, int you?”

The dance will be held in the war memorial hall, “to remember the dead”; we know the characters live on an island prone to flooding; the wind is rising; and Mrs. Reeves is not the most able of baby sitters. And we have already read “The Boat Trip.” So when Gwynnie steals out that night, lured by these new feelings for Johnny Deakin, to walk again along the sea wall, we are there with her, our hearts pounding. This time:

The water’s just off the top of the sea wall. Waves slap against it viciously, sending up cold drops of spray that hit me full in the face… later… (I) can see the white spray arcing over the wall, high above my head. A sudden “what if?”

We are primed, and we are being led along by the hand by a master story-teller, so when the tragedy strikes the emotional impact is as huge as any writer could hope.

Even when the sea is not there, it is present through its absence, in the penultimate story, “Airside.” There’s a beautiful moment where the daughter comes back from her school tour and her Mauritian father is trying to find out which beach it was on a map. She does not know, so she says nothing. “Now he looks sad as he puts away his maps.”

Not all the stories in SaltWater are centered around the sea, however, and it’s interesting that these were the stories that worked the least for me. In “Freshwater Habitat,” Conleth brings his “hard-to-please exotic Japanese girlfriend” back to Navan, his home town. He shows her the fields he has bought beside the Hill of Tara, a national monument, and which he intends to develop. His plans seem rather naive and out of the character of a successful stock broker (but perhaps that is for the reader with the benefit of the hindsight of the demise of the Celtic Tiger). Conleth’s desire to go fishing, and the fish on the back of the coin feel shoehorned in to fit with the overall theme. While SaltWater and Other Stories would have been perfectly acceptable, “Freshwater Habitat,” “Neap Tide,” and “Fish Tank” seem to me to lack, not the sea, per se, but the fully drawn characters of Ashfeldt’s sea-centred stories, and their tension, and the emotional impact that these create.

Ashfeldt’s strengths as a writer are numerous. Her stories are love stories to disparate coastal landscapes; the language she uses to describe them is the language of love, the grá she has for the sea. However, it is not just the sea which is imprinted in Ashfeldt’s DNA; she also has an intrinsic feeling for the rhythm and tension and pacing that makes a good story. It is the steady shiver of dread which permeates SaltWater, ensuring that we can never be quite at ease, can never sit back and enjoy the scenery, which takes it out of the ordinary and gives the collection its edge.

+++

+