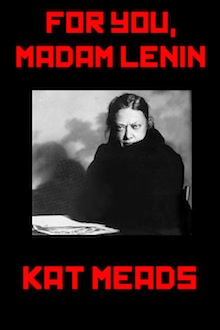

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Kat Meads writes about For You, Madam Lenin (Livingston Press).

+

Vladimir Lenin loved to wash dishes (and other discoveries)

Quite a few of my North Carolina relatives consider my interest in Russian history odd and have told me so. On several occasions. Although “odd” isn’t the term they generally use. Generally they prefer the more damning Southern summation “peculiar.” As in (kin of Kat): “I can understand you wantin’ to write that last book. The one about the farmers and the dust. But this Madam Lenin thing. How’d you get on that? We don’t even come from Russia.”

Quite a few of my North Carolina relatives consider my interest in Russian history odd and have told me so. On several occasions. Although “odd” isn’t the term they generally use. Generally they prefer the more damning Southern summation “peculiar.” As in (kin of Kat): “I can understand you wantin’ to write that last book. The one about the farmers and the dust. But this Madam Lenin thing. How’d you get on that? We don’t even come from Russia.”

And then they give me the squirrelly eye, waiting for me to “explain myself.”

Which I can’t. Not really. Not accurately. Not totally. One semester as an undergraduate at UNC-Chapel Hill, for reasons I can’t remember, I signed up for History 31: Russian History. It turned out to be an excellent class, riveting actually, taught by a professor who bore a faint resemblance to Leon Trotsky. After that introduction, I took every Russian history class I could take at UNC and started accumulating the books that eventually required rooms of bookshelves to shelve them and came to be referred to by friends as my “Russian archives.” The great bulk of those books concern the Russian Revolution. I have tolerant friends, but even the tolerant grow weary of endless talk about interests they don’t share. One fine day, as I yakked on about my latest Russian Revolution reading, one of those friends, not quite in jest, remarked: “Still hoping that story’s going to turn out differently, are you?”

Point taken.

But here’s the thing.

Of the various Lenin biographies I’d read, none before Robert Payne’s The Life and Death of Lenin delivered this information/revelation: Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya’s mother, Yelizaveta Vasilevna Krupskaya, was a woman who had “a tart tongue…liked to have her own way and stood no nonsense from anyone.”

Vladimir Lenin living cheek-to-jowl with an opinionated, tart-tongued mother-in-law.

That description set my fictioneer’s brain a-churning.

Prior to reading Payne’s biography, I hadn’t, for a second, contemplated writing a novel involving the domestic triangle of Nadya Krupskaya, Yelizaveta Krupskaya and Vladimir Lenin or the Russian Revolution of 1917. Most certainly I’d never thought of writing a novel that included a character named History who interrogated women radicals.

But after Payne’s prompt, one notion led to another.

To better prep for what would become For You, Madam Lenin, I read more documents, started scouring photographic collections, watched the BBC’s “Fall of Eagles” series, The Assassination of Trotsky, Alan Rickman’s cinematic turn as Rasputin and a slew of other films and documentaries, filled 40-odd notebooks with quotes, timelines and various English spellings of Russian names, congratulated myself on finding a clip of Nadya Krupskaya/Madam Lenin on YouTube and took a trip to Russia. But when I dug into the historical record this go-around, my motive was novel making. Which meant I wasn’t so much looking for facts or another author’s interpretation of those facts as I was hunting for details, asides, implications — even speculations — that could be used and manipulated to fictional advantage.

For example.

- In Siberia, Vladimir Lenin washed the household’s dishes and sang while doing so. Makes for quite the picture, doesn’t it? The exiled agitator standing at the sink, singing “You Have Charming Little Eyes.” I thought (and think) so.

- In the rat-infested Kremlin, the Lenins had cats for pets and during their Siberian exile owned a hunting dog. During the course of my novel, NK owns two other dogs: one as a child in Poland and one given to her in Gorky during Lenin’s prolonged dying. In my invention, along with many other sacrifices, NK is forced to give up her dogs.

- According to C. Bobrovskaya’s pamphlet, Lenin and Krupskaya (Workers Library Publishers, 1940), NK wrote this sentiment to a comrade about a Kislovodsk vacation: “I don’t like things here. I feel very queer with no work to do — like a fish out of water.” In my novel, even when she could have taken a breather, NK worked.

- Of her romantic rival for Vladimir Lenin’s affections, Inessa Armand, NK writes in Memories of Lenin: “Inessa was a very ardent Bolshevik and soon gathered our Paris crowd around her.” Quite the understatement, given that her besotted husband chiefed that fawning crowd.

- In Paris, Lenin’s mode of transportation to the Bibiliothèque Nationale was a bicycle. Returning home one day, a speeding car forced him off the road. When Lenin found out the driver was a vicomte, he sued, won the case and in compensation received a new bicycle. In my novel, Yelizaveta Vasilevna has great fun mocking her son-in-law’s bicycle fetish.

- In her writings, Nadya Krupskaya downplays the anxieties and dangers facing the Russian socialists who traveled through Germany on the famous “sealed” train on the first leg of their return trip to Russia in 1917. In NK’s writings — and very likely in her true opinion — it was all about the triumphant return to St. Petersburg/Petrograd and the adoring crowds shouting Lenin’s name at the Finland Station. Fiction is allowed — encouraged? — to elaborate on anxiety. In Madam Lenin, Yelizaveta presents the contrapuntal jittery version to NK’s revolutionarily correct account of that journey back to the motherland.

- After Lenin relocated the government to Moscow, the Lenins were interviewed in the Kremlin by American journalist and fellow Communist Louise Bryant, who subsequently published an article fulsome in its praise of and admiration for the couple. Were the Lenins equally impressed by the journalist? Probably not. In my novel, definitely not. NK is incensed by the presumptuous American, describing where and what she and husband John Reed were doing as the Provisional Government collapsed.

- As a series of strokes rendered Lenin more and more disabled, he and NK stayed in Gorky, isolated and, historians seem to agree, spied on by those now loyal to Stalin. Regarding the telephone call in which Stalin spoke “rudely” to Comrade Krupskaya for talking politics with her husband after the doctors had forbidden such upsetting discourse, the historical version is dry indeed. A telephone call that provoked the never hysterical NK to hysteria and resulted in Lenin suffering another stroke is (in my opinion) high drama. In my novel, in that scene, I try to deliver high drama.

- After Lenin’s death in 1924 and until her own death in 1939, Nadya Krupskaya continued to live in a Kremlin apartment. That is, she lived in close proximity to the Red Square mausoleum that she had argued against constructing, the over-the-top memorial that held her husband’s corpse. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine NK’s reaction to that daily visual, and I wrote what I imagined. To stick with a semblance of the historical record, I couldn’t, at novel’s end, have Nadya Krupskaya triumph over Joseph Stalin. But I could have her stubbornly endure. Which I did in fiction and which she did in life.

In 2006, finished with my info collecting and note taking, almost, almost ready to plunge into writing the first draft, I made a quick trip to St. Petersburg, hometown of another Vladimir, Vladimir Putin. It wasn’t the Russia of Krupskaya and Lenin, but it was Russia. While there, I slept in the Hotel Astoria where Louise Bryant and John Reed were lodging when the Bolsheviks prevailed. I wasn’t able to get into room 188 of the Winter Palace, the dining room where Provisional Government holdouts were arrested by the Bolsheviks, some of those officials dragged out from under the table during the transfer of power, but I was able to linger in Palace Square, site of the Bloody Sunday massacre in which the tsars’ military reps slaughtered civilians. I didn’t visit the cell in the Peter and Paul fortress that had held Lenin’s doomed brother but I did stand within throwing distance of Nicholas II’s bones in the Peter and Paul Cathedral, inside the Peter and Paul Fortress. Neither I nor my guide could precisely locate the apartment off Nevsky Prospekt where Nadya and Yelizaveta Krupskaya had lived before Simbirsk native Vladimir Ulyanov entered their lives, but I did visit the room where Prince Yusupov tried and failed to poison Rasputin and there heard my guide declare, to my astonishment, that “all” tales about Rasputin’s debauchery and influence over the tsarina were “fabrications,” — an assessment that had me bug-eyed for the rest of our touring time together and pretty much throughout the multiple flights required to get me back to San Jose, California.

In my fabrication, Yelizaveta Vasilevna is the narrator who calls a fig a fig, a Menshevik a Menshevik and a failed revolution a failed revolution. In the single photograph I found of Yelizaveta, she does indeed give the impression of a woman who brooked no nonsense. In the photo I saw, she has a sharp nose. In my fiction, instead, she has a sharp chin. Which is to say I did the research, but then, for story’s sake, I mucked and fudged.

+++