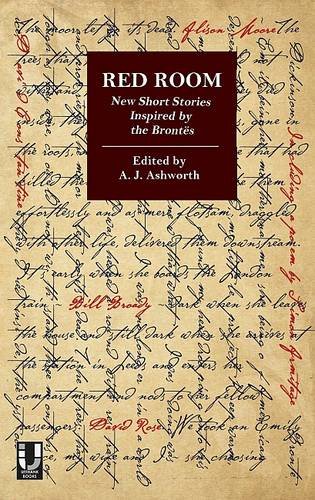

Unthank Books, 2013

In her introduction to Red Room: New Short Stories Inspired by the Brontës, editor A.J. Ashworth tells us that the anthology came about as a rescue attempt, a way to help save the original Brontë home (in a village called Thornton in West Yorkshire) with the hope of giving it some sort of historical protection. This modest stone building has seen all manner of incarnations and is currently a private home. That the Brontës—now almost exactly 200 years after their births—are involved in a struggle very much related to a notion of home is sad but also quite fitting. Home was a difficult place for the Brontës—most definitely a place of solace and creative inspiration, but because of their father, their relative social poverty and certain eccentric personality traits all their own, also a place of oppression and restriction. And most of their work connects with this idea quite powerfully, with varying levels of complexity.

The first story in Red Room, “Stonecrop” by Alison Moore, charges headlong into this idea of home in a most intense manner. It is a short and sneakily dangerous little piece of writing with a number of sharp and glinty darknesses winking out from amidst its careful sentences and pastoral pretext. The question in “Stonecrop” is about survival, private and intimate access, and about deciding who gets to be a part of one’s home.

In a similar way, in David Constantine’s “Ashton and Elaine,” we get a deep look into how a person goes about finding a home. What are the rules and boundaries of that word? How can they conjure up such opposite notions? Safety on one hand, terror on the other. As the story opens, Ashton, a child, is found shivering and broken under a tarp behind a market stall. The reader does not, thankfully, ever get the details of what exactly happened to Ashton before this moment, but Constantine gives us enough hints to know that we might not be able to bear it. The story then follows his rehabilitation, his life at a special school and eventually, his adoption into a kind family. It is a gentle story in many ways but it contains a chilling violence and Ashton’s past haunts each page, each interaction. Like “Stonecrop,” “Ashton and Elaine” is inspired by Wuthering Heights and Constantine skims along the emotional current of that novel in a spectacular way.

Before I make it sound otherwise, there is not only darkness, grief and brooding in these stories. Vanessa Gebbie, Tania Hershman and Felicity Skelton each provide a splendidly mischievous expression of Brontë-inspired fiction. Skelton begins “The Curate’s Wife—A Fantasy” with the first line from Jane Eyre (“There was no possibility of taking a walk that day.”), throwing us immediately into Charlotte’s world, but not the fictional setting of Jane Eyre, this story places us in Charlotte’s real world, of around 1852 or 1853, just before she would marry Arthur Nichols. The story, which is daring in a way that might be uncomfortable for purest fans of Brontë fiction, plays successfully both with actual history and the myth of Charlotte Brontë.

Hershman’s “A Shower of Curates” weaves several Brontë first lines together into a gleefully sinister story of land acquisition. The narrator here is a pure pleasure to read—a hand-rubbing, draught-imbibing, spying vulture of a man who speaks as though he’s a harmless bumbler. Even within the temporal and inspirational confines of such a project, Hershman does energetic narration so well:

And what of these curates now? I feel them crawling to their places, I send out webs to each in turn, they are obedience personified, although not quite person, of course! They slink to their parishes, their teeth whiter than the whitest dentures you, my friend, will see, their smiles broad, their Biblical quotations sheer perfection.

Perhaps the most outrageous (and also outrageously funny) of these mischievous pieces is Vanessa Gebbie’s “Chapter XXXVIII – Conclusion (and a little bit of added cookery) with abject apologies to Charlotte Brontë.” Gebbie rewrites the ending to Jane Eyre and keeps her tongue firmly in her cheek while doing so. This is a wickedly clever Jane, emphasis on wicked, and one I suspect Jean Rhys would greatly admire as we watch her dispatch the servants and others to arrange her domestic life to suit her own happiness, a Jane that can listen, unperturbed, as Rochester utters an expression like “rumpy pumpy.”

There are also stories that engage with the melancholy of the Brontës, like David Rose’s beautiful “Brontesaurus” and Carys Davies “Bonnet.” The first is an elegant story of loneliness and academic solace, a piece that worries away at words like grief and drear in first a strictly literal manner and then a more emotional, more metaphorically delicate way. In “Bonnet” we are back to contemplating the real Charlotte Brontë in an imagined scene that quite possibly could have taken place and that gets at the heart of Charlotte’s conflicting personality: the passionate writer, the careful lover.

The range of subject and theme in the other stories is quite impressive: the deceptions of a modern-day governess, the death of a loved one, a contemporary Catherine & Heathcliff romance, a hike on the moors invoking Sherlock Holmes and much Brontë lore, and even fictional letters between Emma Woodhouse and Jane Eyre. As a purely selfish wish, I would have enjoyed a bit of direct engagement with Anne Brontë, she seems so often overlooked and yet her works are as powerful and complex as her two more studied sisters. And it is fun to speculate what a story inspired by Branwell or the Brontë children’s fantasy worlds of Angria or Gondal might have added, but this is not to say that Red Room feels incomplete, only a little Charlotte-heavy. As a whole, Red Room is a provocative, emotionally-engaging and witty anthology. It is clear that the authors featured here took to their task with both application and admiration.

Finally, in her excellent biography of Charlotte Brontë, Lyndall Gordon makes a comment about Villette, saying that this book asks more of its readers than Jane Eyre, that it asks for, “the reciprocal action of a reader alert to secret lives.” This to me is the essence of connecting with Brontë fiction, mythology and biography—that as readers we remain open to and interested in what is hidden and unsaid, in all that peeps in at windows and lurks outside in the dusk, that we embrace the furtive but far-reaching undercurrents of such complex personalities within their literary endeavors. Red Room does just this, engaging with the “secret lives” inside the legacy of the Brontë world and offering up numerous new possibilities.

+++

+

+