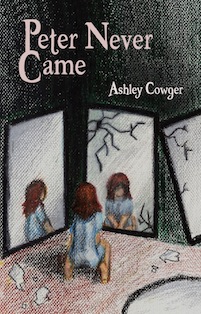

Autumn House Press, Jan 2011

Today is Monday. Tomorrow will be Tuesday. Then comes Wednesday and so on and so forth. Time ticks on and we are forced to experience each new day, feel ourselves transformed by the passing of time. We may be able to stand still or take steps backward, but we cannot avoid being swept up in this forward movement. And yet humans are rebellious creatures. We fight this notion, waging our desperate attacks against Time, refusing to engage with its influence.

The stories in Peter Never Came, by Ashley Cowger, are like so many artifacts of our rebellion, and they take as their mascot that most famous Time-rebel, Peter Pan. This is not to say that Cowger’s stories are harmless, playful tracings of the all-too-human desire to somehow avoid growing up. Cowger is interested in how this longing for the simplicity of childhood can disrupt a life, can cripple the adult harboring this desire. She is also quick to point out the falsity in assuming either side of the equation—childhood or adulthood—to be some kind of promised land.

Excepting the two (both excellent) stories which bracket the larger collection, labeled Prologue and Epilogue, the eleven stories in Peter Never Came are divided up and settled into three categories: Pan, Interlude and Pirates. These headings, clever but perhaps ultimately unnecessary, walk the reader along a spectrum from youth to maturity.

The five stories in Pan are each a commentary on childhood innocence. In “Shades of Blue” a child is mourned by a community, his obvious goodness fixed in the minds of those who attend his funeral, and the reader’s too, until the narrator subverts this by predicting all the horrible things Tommy would have done had he actually been able to grow up. “Boy Scout Finn,” on the other hand, affirms the beauty of one child’s true innocence, revealing the ugliness of the adult world by comparison.

One of the most interesting stories in the entire collection is the last in this section, “The Kind That Can Be Real,” a surrealist nightmare about a young woman named Rhetta, her doll Mindy and what happens to a person when childhood literally never ends. This is the most dangerous kind of Peter Pan fantasy, when make-believe triumphs completely over reality.

The single Interlude story, “The Things We Take and the Things We Leave Behind” is, admittedly, the least spectacular of the entire collection. A young man and woman sit together preparing for a move, packing their lives into three boxes each – a limit imposed by the size of their car. The young woman is unable to shed her childhood mementos, a failure which prevents the couple from finalizing their move. This is as far as the story goes, yet it most neatly articulates Cowger’s overall vision:

I want to tell him that I’d like to believe that what we had when we were children we can still have when we grow older, that there are some things in life worth holding on to, but the words would sound hollow and I know they aren’t true.

The tone of the collection shifts with the first story in the Pirates section. If childhood wasn’t easy, then adulthood will be even harder. This is a place where disillusionment has set up a fortified little camp and absolutely refuses to let anyone out.

Take “Nature,” for instance, a story about the failed kidnapping of a young woman named Liz. This piece is about a loss of innocence so great that it forces Liz to confront her deepest animal nature, and now the rest of the world has become distorted. The night after she escapes from “the man,” she cannot sleep and so goes out into her garden:

She looked around the garden, really looked for the first time in she didn’t know how long. There were several dandelions, and some little purple things that she hadn’t planted either. The ones that she hadn’t planted were the ones that looked the strongest, the ones whose blossoms were full and beautiful.

Weeds.

They must be choking the life out of the plants she had wanted to be there, had carefully picked out and planted one by one with her own hands.

She tossed the dandelion onto the ground and then moved on to the next living thing, and the next, pulling up clumps of flowers and weeds and tossing them into small piles on the earth. By the time Toby got up, she had uprooted every flower and plant in the garden that she could find and was raking them into a giant pile of detritus in the center.

The title story, “Peter Never Came,” about a couple faced with an unexpected pregnancy and opposing views of how to handle the situation, seems nearly tame in comparison. Yet Cowger is careful to show what is really at stake for her first-person narrator—she is the Peter Pan of the collection, a young woman who would have preferred to remain in Neverland, skipping over adult pleasures for the true bliss of childhood play.

All in all, Peter Never Came is a promising debut collection. There are moments when the writing could have been pushed a little further, when a narrator might have used a different way to express an idea to keep it from sounding overly ordinary, when Cowger might have tried for a bit more lyricism. Yet her ideas are original, even daring, and it is clear from the accomplishment of this collection that she is a young writer to celebrate as we look forward to her next offering.