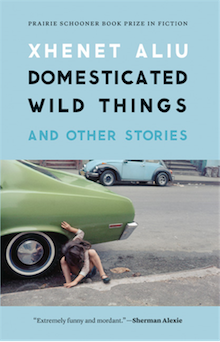

Our Research Notes series invites authors to describe their research for a recent book, with “research” defined as broadly as they like. This week, Xhenet Aliu writes about Domesticated Wild Things and Other Stories (University of Nebraska Press).

+

Recently I read a Goodreads review of a story collection that cautions the readers that the stories are based on real people with whom the author grew up, including the reviewer’s in-laws. The stories, according to the reviewer, are offensive. The stories are offensive, the individual writes, because they could not be further from the truth.

Recently I read a Goodreads review of a story collection that cautions the readers that the stories are based on real people with whom the author grew up, including the reviewer’s in-laws. The stories, according to the reviewer, are offensive. The stories are offensive, the individual writes, because they could not be further from the truth.

I wouldn’t define fiction as being the furthest thing from the truth, at least not the emotional one. For me, good fiction is the most direct route to it, an exercise in empathy via imagination that widens the lens through which I see the world off the page. I will venture that what the reviewer meant is that the stories in the collection could not be further from representing what actually happened, but it seems redundant to point that out, because the reviewer is describing a work of, well, fiction. But if the characters in the story in question were actually the furthest they could be from who these people really are, or if the events couldn’t be further from what really took place, how would the reviewer have recognized his or her in-laws in the first place? Did the author of the collection violate the rules of fiction or the rules of etiquette — or both, or neither — by making his characters a little bit real?

It’s interesting to me that the first entry for fiction in the OED states it’s “the act of fashioning or imitating,” and the second is “arbitrary invention.” The definitions seem so different, and yet they play so well together, or at least it they seem to on my computer screen when writing my own stories. The reviewer of the above-mentioned collection obviously read the stories as a type of mimicry, which, whether it’s intended as such or not, is easily taken for ridicule, but no other reviews complained of flat characters, so the affront appears pretty specific. Still, now that my own collection has been released, I can’t help but feel an urge to preemptively explain to those who might recognize bits of themselves in the stories, when they protest But that’s not what happened, that of course it’s not. I would explain to my childhood best friend, whose family was so nurturing to me when it was most critical, that I was able to write about violence and violation through characters that shared some of her family’s characteristics because I felt secure enough in their presence to let my imagination probe the what-ifs more deeply. I would explain that while I did briefly date a guy who bred venomous reptiles, the fer-de-lance in “Two-Step Snake” is a stand-in for the foreboding I’ve felt in relationships with other people whose facsimiles aren’t in any obvious way on the page. I would explain to my mother that she does not resemble any of the terrible mothers rampant in the collection, that it’s possible I might just be exploring my own rejection of maternity.

It’s too late for me to worry about etiquette breaches now that my stories are public, but I do still wonder if there’s a clearly defined threshold between person and character, if borrowing your cousin’s, say, wardrobe and career choices for a character in a story but inventing his gerbil obsession is acceptable. Would the opposite be? How much has to be invented for it to be offensive? How much has to be true for the same? Where are the lines between biography and libel and just a story? If the vast majority of readers can’t gauge the distance between the original and the copy because they don’t even know an original exists, do the delineations matter?

This isn’t intended as an apology, because if it were, it would be insincere — as a fiction writer I don’t feel compelled to apologize for making the stories on the page match the contents of my head, which contains a whole lot more than just memory. It’s just an interesting space to navigate, especially now that it’s no longer just a private concern: this realm between my own and others’ truths, the channels between literal truth and the emotional one that I feel a greater responsibility to. Ultimately, anyone who reads Domesticated Wild Things has a valid right to declare that the stories within could not be farther from the truth, but I hope that the conclusion isn’t reached because they don’t reflect what actually happened.

+++