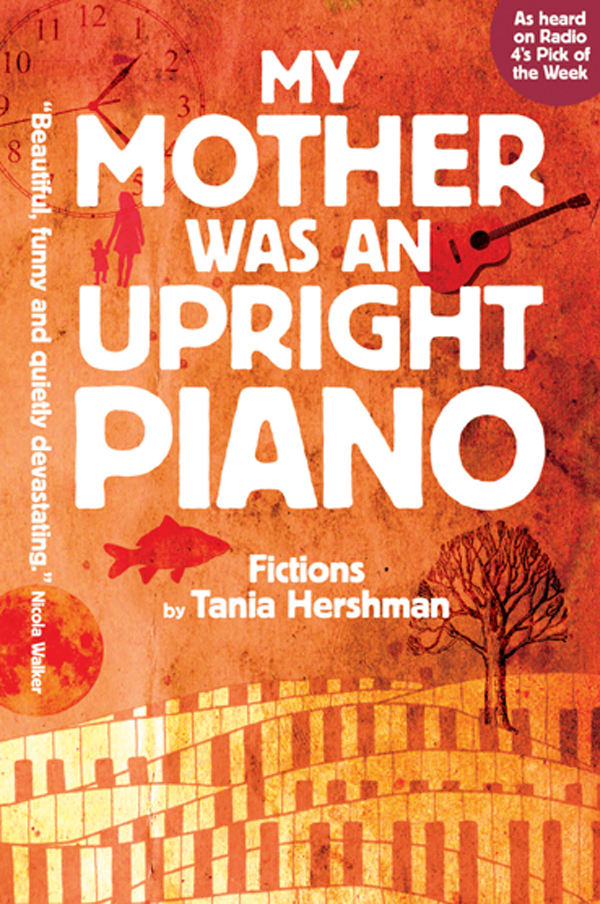

Tangent Books, 2012

Very short fiction is a versatile medium—it often functions like a poem, creating an impressionistic and exploded universe of a specific emotion, thought or interaction; just as often, a piece of flash comprises a single, distinct microstory, meant to represent a larger or universal experience. It can also work, and often does, in combination with another medium, a painting or a photograph or another fiction, and in this way it becomes a form of translation, re-envisioning, homage or explanation. These first types of very short fiction more consciously embrace the confines of the form, embracing the very idea of truncation and integrating any related narrative “boundaries” into its internal aesthetic. But flash pieces can also work in another direction entirely. They can willfully ignore or resist this idea of “boundaries,” and, in this way they create a sharp and refined glimmer of a much longer story. But they are more than a hint of a longer story, they are like a puzzle piece so intricately detailed and perfectly formed that it no longer needs the puzzle.

This last example is the kind of fiction that mostly fills Tania Hershman’s My Mother Was an Upright Piano, a collection of fifty-six short and very short fictions that play across a wide variety of human experience and emotion—loss, irreverence, love relationships, family relationships, grief, anger, curiosity, escape. The diversity of subject on offer in the collection is brilliant, but what really impresses is how Hershman succeeds in establishing longer, more complicated narratives within each short piece. These aren’t incomplete excerpts; the reader doesn’t want or need any of these fictions to go on longer or somehow become another form entirely. But again and again, out of a very short piece, a fuller story blooms.

There are several great examples in which Hershman accomplishes this: “tiny unborn fish,” “like owls,” and “graveside” are the first to come to mind—but in “under the tree,” the effect is perhaps the easiest to see. “under the tree” is a simple but stunning story of a mother and a son, told in the mother’s voice. One morning the son goes out to sit beneath a tree in the garden, and he doesn’t get up. Not for days. The story details the mother’s bewildered reaction, quickly followed by her panic and eventual desperation. The piece is less than a thousand words and yet it’s an entire novel of family loss, parent-teenager relations, and public vs. private emotional display. Here is just a hint:

fivedayssixdayssevendays

My mind’s gone on holiday. I’m Robot Mum, preparing food, serving food, lips moving, brain frozen. He’s under the tree, still under, still the tree, and trains of thought are barreling at top speed, carving ravines through me, losing, loss, empty, gone. I’m Pleading Mum now, almost on her knees, whiny-voiced, Why? What are you doing? Please, darling, please, stop this, please please please, and him placid, unmoving, unshakeable. I’m the storm and he is rooted, I try to pull, he digs even further in, and we are standing still, still standing, sitting, he is, and crumbling, I am.

Another particularity of My Mother Was an Upright Piano is Hershman’s obvious love of science and her delight in playing with and questioning and commenting on scientific ideas. Sometimes the science is done in a relatively straightforward manner, like in “the painter and the physicist” or “vegetable, mineral”—both stories in which the scientific ideas become an alternative structure for working out tricky issues of human interaction. Hershman has a knack for putting science into a new context and creating those tiny moments of revelation out of contrast.

But more often than the straightforward, her pieces veer toward a subtle magical realism or fantasy. There is something wonderfully weird about many of these pieces, and many reminded me of the unsettling but always enchanting artistic vision of Terry Gilliam. In, “the beam line,” for example, where a column of people stand together waiting for entrance to a building, not knowing what they’ll find inside, but forced to simulate real joy while they wait. And they submit to this, and their submission eventually becomes its own form of joy. It’s sinister and eerie.

There’s also “disease relics,” a mini-dystopian tale about an assembly line and an uncommon connection between two workers. In this piece, the visuals are startling, especially held against the otherwise ordinary nature of the narrator’s thoughts:

I was there then, busy, learning how to graft. I had my parts then, when I started. But some time passed and then my small finger on the left hand, became a slice of sock. It didn’t hinder. I could make do, just fine. My job there was to sift the flakes, all sizes there, from blanched moths up to carpets, some. Gloves we wore always, special ones, and then fitting my finger in was odd. But in the end it worked.

Gathered together into a collection, Hershman’s fictions have a pleasing harmony. Despite the variety of subject and even the varying directions of experiment that Hershman follows, the pieces speak to one another through their innovative and unusual way of looking at and re-imagining the world. While there are several “serious” pieces that achieve an appropriately serious reader response, the overall tone of the collection is somewhat lighter and seems more interested in promoting curiosity about the extremes of human emotion rather than abject grief or despair. All in all, the fifty-six stories in My Mother Was an Upright Piano represent one hundred and thirty-two pages of fictional delight.

+++

+