Twisted Spoon Press, 2014

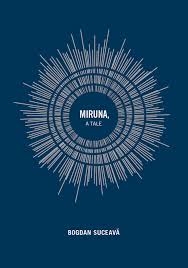

The first bit of front matter a reader encounters opening Twisted Spoon Press’ new English translation of Bogdan Suceavă’s Miruna, A Tale is not a title page, or a copyright page, or a list of the author’s titles to date. It is a black page ornamented at its center with an intricate series of concentric circles that calls to mind a wheel, a target or a void. Suceavă’s “About the Author” page notes that he is a professor of mathematics at California State University, hinting at the significance of the design. One only has to read so far to realize that the image is a rendering of the structure of the novel.

With twenty years of hindsight, a man remembers visiting in his childhood with his grandfather and listening to his grandfather’s stories about his own father as well as his apparent namesake, an ageless woman with magical powers, and many other characters who represent figures important to the history of their family and their village and the folklore of their culture. The narrator is Trajan Berca, the grandfather is Niculae Berca, his father is Constantine Berca, who fought in the Romanian War of Independence of 1877-78, and Miruna is Trajan’s sister, who hears the stories and receives them as if she has an innate capacity to register them. Reading Miruna, one is tempted to read and reread certain passages from the beginning in order to locate the single source of a given tale or to discern definitively from whose perspective the tale is being told; this is a fool’s errand. Suceavă writes at once for an entire family of storytellers, an entire village of gossipers, and decades of issues of a local newspaper. Any given sentence of Miruna can just as likely be a portal into the center of the earth dug by the hand of Niculae Welldigger, a prophecy read from the images engraved in grains of rice by Old Woman Fira, or, more likely, both.

Within each uninterrupted chapter, stories will pass into others gradually, as one chain of telling ends and another continues and another begins. After Old Woman Fira renounces her powers at the urging of the priest Father Dimitrie, Trajan tells us that Constantine Berca was among the first to sense the absence of her magic:

One of the first people who felt the lack of Old Woman Fira’s powers was Constantine Berca, because he could have used their help in the story of Enache Mâzgău and the curse.

In this instance, the end of one story and the beginning of another are contained in one sentence, but the beginning of this second story will not come until another is told, because the story of Enache Mâzgău and the curse cannot be recounted until the story of Constantine Berca’s courtship of Domnica Râmniceanu is told. Therefore, in this sentence, one story ends, another begins, and the space between these two is filled immediately afterward by a third. Once the reader starts to pay attention to these intricacies of structure, the book opens up and becomes manifold and tremendous. The book progresses from beginning to end, but with every sentence stories are beginning and ending and beginning again.

The story of Constantine Berca’s courtship of his spouse, Domnica, begins when he hears a song and follows it to the heart of a wood. He meets Domnica’s father and begins the process of asking after her hand, but he is unable to persuade the man immediately and this story is soon interrupted by another, the story of Niculae Welldigger’s search for water on Berca’s plot at Old Knoll. Buffered now by several layers of narrative, he falls into a deep sleep where the plot overlooks Evil Vale (the center of the novel’s system of action), and Trajan describes his slumber thus:

But Constantine Berca fell asleep on the spot, without having had time to find any shelter, without thinking any more about the well or his farm, and he slept such a sleep that the dam of dreams opened and received him inside as though into a citadel, surrounding him as though in a mist with walls and towers and red shadows, like those of a latter-day Jerusalem, which will reveal itself at the end of the ages, or so it is written.

As the tales within the larger tale begin to overlap, language accumulates around the characters. There is a series of concentric circles inside this sentence. In his sleep, dreaming a tale that is another tale within the larger universe of tales, Berca is surrounded by the walls of a castle and flanked by the past and the future.

This linguistic elasticity pervades the book along with the density of concurrent narratives, until Trajan finally reveals to us, in the words of his grandfather and his village and his people and his planet, the design of the novel, and the nature of narrative as Suceavă understands it:

Numbers are in fact of no use to anyone, because nothing ever changes. Evil Vale is always the same. The ages of man are not like the ages of trees, for they are not measured in the same way. Birds of prey do not live as long as hens, or wolves and bears as long as cats. Things cannot be gauged by the same measure. Time is different for each thing. And the fact that Old Woman Fira, Elifterie, and Father Dimitrie are all still alive, just as aged as they were when Niculae Berca was a child, is merely a matter of dispensations from the laws of nature that allow time to beswathed like a shawl around certain people, a disturbance that is called deathless life, about which there is an old fairy tale where the most interesting character is not the scorpion or the woodpecker but time itself.

A note at the back of the book reveals that there is in fact an old fairy tale from Suceavă’s native Romania called “Unaging Youth and Deathless Life,” and the concept articulated by this title and rearticulated by Suceavă justifies the continual recurrences the novel traces and the retelling of folktales that is the novel’s true project. At the center of Suceavă’s series of concentric circles is a first teller of the story of the human race on Earth, so diminished by time as to be invisible, and the outermost circle is Suceavă’s novel, the retelling that contains all other retellings. Once this secret of the novel is revealed, it becomes obvious that the subtitle A Tale is an ironic one. For Bogdan Suceavă, there is only one tale, and to attempt to tell another is only to get lost in its ever-expanding orbit.

+++

+

+